As this year and this list come to a close – the former a period of recovery from cancer and its treatment, and the latter an exercise in personal reflection – things boil down to a final few hours and five final songs.

As this year and this list come to a close – the former a period of recovery from cancer and its treatment, and the latter an exercise in personal reflection – things boil down to a final few hours and five final songs.

Again, for those new to this, what you’ll find below are the final handful of songs on a list I began this spring as I lay recovering from Stage IV throat cancer. It is of my 300 favorite singles of the 1960s, along with a brief (or at least brief-ish) narrative on why a song matters to me, or at least some memory or reflection I have of it.

These are not by any means the 300 best 45s from the Golden Age of Top 40 radio, or even my opinion of the 300 best. They are simply my 300 favorites; those songs that have not been beaten to death by oldies radio or co-opted by some combination of Hollywood and Madison Ave, and with which I maintain various levels of personal attachment.

Two things before I bid this project adieu. First, the narratives that accompany these last few songs have grown in length as the songs become nearer and dearer to my heart and/or mind. For that I apologize.

Two things before I bid this project adieu. First, the narratives that accompany these last few songs have grown in length as the songs become nearer and dearer to my heart and/or mind. For that I apologize.

And secondly, I’d sure appreciate your feedback and would love to hear your thoughts, either on 45s that you too liked, or one’s that would have made your cut but did not make mine.

And finally, unlike each other installment, this time I thought I’d change things up. Rather than listing the 45s in numerical order, I’m listing them in inverse numerical order, with #5 first and #1 last.

Thanks for all your support and feedback throughout this process. Here’s to you, here’s to music, and here’s to a great 2015.

Enjoy.

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 1

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 2

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 3

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 4

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 5

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 6

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 7

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 8

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 9

Desert Island Jukebox: Songs 26 thru 30

Desert Island Jukebox: Songs 21 thru 25

Desert Island Jukebox: Songs 16 thru 20

Desert Island Jukebox: Songs 11 thru 15

Desert Island Jukebox: Songs 6 thru 10

5. Not Too Long Ago

Uniques

1965

A Louisiana country boy from rural Webster Parish, near Bossier City, Joe Stampley grew up listening to everyone from Hank  Williams and Merle Travis to Elvis Presley, Dale Hawkins, delta blues, traditional Creole, race records, and Cajun style boogie-woogie. So when he formed a band and heard local critics were having trouble pigeonholing their eclectic and often one-of-a-kind music, Stampley decided to call his group the Uniques. This one wasn’t the Uniques biggest selling record, but it was their best – and by far. A tune written by Stampley himself, along with country great Merle Kilgore (Ring of Fire), the 45 was produced by the aforementioned Hawkins, who even though he had written and released the rockabilly smash hit Susie Q a few years prior, remained still a largely local hero. Yet, for some reason (maybe because it was the first-ever single on Paula Records, a tiny independent label from nearby Shreveport), this one rose to no higher than #66 on the charts, where it floundered for six weeks before disappearing

Williams and Merle Travis to Elvis Presley, Dale Hawkins, delta blues, traditional Creole, race records, and Cajun style boogie-woogie. So when he formed a band and heard local critics were having trouble pigeonholing their eclectic and often one-of-a-kind music, Stampley decided to call his group the Uniques. This one wasn’t the Uniques biggest selling record, but it was their best – and by far. A tune written by Stampley himself, along with country great Merle Kilgore (Ring of Fire), the 45 was produced by the aforementioned Hawkins, who even though he had written and released the rockabilly smash hit Susie Q a few years prior, remained still a largely local hero. Yet, for some reason (maybe because it was the first-ever single on Paula Records, a tiny independent label from nearby Shreveport), this one rose to no higher than #66 on the charts, where it floundered for six weeks before disappearing  altogether – never to be heard from again. And maybe that’s why this one sits on such a lofty perch here. Because not only do I continue to love it just as much, if not more, as when I was a wide-eyed ten-year old kid running around with a bat and glove in hand, and a pocket transistor glued to my ear. But more that that, it is a flat-out stunning pop record and delicious mélange of musical influences. And perhaps just as important, it has never been played to death; not during its original release; not during any Hollywood-fueled second life; and certainly not during the past five decades, during which it seems corporate radio has been hell-bent on trying to whittle down the rich, complex and wildly diverse soundtrack of our lives to 40 or so tunes that they could then re-package, tie in a pretty bow, and cram down our throats as intellectual shorthand for the salad days of our youth when a song like Not Too Long Ago would touch us, move us and change us, if only subtly, in ways no creative director, account exec, market analyst, or corner office suit could ever begin to comprehend.

altogether – never to be heard from again. And maybe that’s why this one sits on such a lofty perch here. Because not only do I continue to love it just as much, if not more, as when I was a wide-eyed ten-year old kid running around with a bat and glove in hand, and a pocket transistor glued to my ear. But more that that, it is a flat-out stunning pop record and delicious mélange of musical influences. And perhaps just as important, it has never been played to death; not during its original release; not during any Hollywood-fueled second life; and certainly not during the past five decades, during which it seems corporate radio has been hell-bent on trying to whittle down the rich, complex and wildly diverse soundtrack of our lives to 40 or so tunes that they could then re-package, tie in a pretty bow, and cram down our throats as intellectual shorthand for the salad days of our youth when a song like Not Too Long Ago would touch us, move us and change us, if only subtly, in ways no creative director, account exec, market analyst, or corner office suit could ever begin to comprehend.

4. Can’t Find the Time

Orpheus

1969

Bud Ballou, a frenetic, high-energy kid from nearby Liverpool, scored his first DJ job at WOLF-AM in my hometown of Syracuse. The year was 1962. And in short order Ballou bayed, brayed, preened, pranced, joked, howled, giggled and spun his way  to local legend status, while at the same time helping usher in Beatlemania, hosting a local dance show on TV, and developing a reputation for uncovering fabulous but largely obscure pop tunes. By the end of the decade, Ballou had station-hopped all the way up the ladder to Boston, where he became every bit the icon that he’d been in Syracuse. And it was there that one day he stumbled upon a single by an unknown local group and began playing the hell out of it, often multiple times the same hour, professing his undying love for the record and urging any kid within earshot to run out and buy it. Within weeks, despite the fact Can’t Find the Time hadn’t come close to charting nationally, it had shot all the way to #1 in Boston. And because it was Ballou driving the train, the single also started to get some airplay back in Syracuse, where I heard and also fell in love with it. Fast-forward three years. ’m now a college freshman and one Friday decided I needed to hitch a ride to Boston, a full seven hours away. For weeks, you see, I’d been hungry – OK, make that desperate – to see a beautiful young woman named Patti. Patti was my first love, and was the one person who in 17 short years I had come to

to local legend status, while at the same time helping usher in Beatlemania, hosting a local dance show on TV, and developing a reputation for uncovering fabulous but largely obscure pop tunes. By the end of the decade, Ballou had station-hopped all the way up the ladder to Boston, where he became every bit the icon that he’d been in Syracuse. And it was there that one day he stumbled upon a single by an unknown local group and began playing the hell out of it, often multiple times the same hour, professing his undying love for the record and urging any kid within earshot to run out and buy it. Within weeks, despite the fact Can’t Find the Time hadn’t come close to charting nationally, it had shot all the way to #1 in Boston. And because it was Ballou driving the train, the single also started to get some airplay back in Syracuse, where I heard and also fell in love with it. Fast-forward three years. ’m now a college freshman and one Friday decided I needed to hitch a ride to Boston, a full seven hours away. For weeks, you see, I’d been hungry – OK, make that desperate – to see a beautiful young woman named Patti. Patti was my first love, and was the one person who in 17 short years I had come to  cherish as no other, a young lady who, after not seeing her for two months, I ached for in just about every way a young man could possibly ache for a woman. Now, in full candor I admit I since have known love that was maybe wiser, more stable and more mature than the love that wrapped itself around me that Friday as we headed down the Mass Pike toward Boston a lifetime ago. But as sure as I’m sitting here typing this, I promise you that the very moment this beautiful little pop single came on that car’s AM radio, and as I sat there alone in the back seat while two strangers I’d met on a ride board drove without speaking and turned onto Beacon Street – one part of my brain listening, while another overflowed with thoughts of Patti, with visions of her eyes, her smile, her voice, her smell and her touch darting through my head – I never had my heart fling more wide open, felt my skin tingle with any greater sense of anticipation, or experienced any emotion, before or since, as deep, as pure, as raw, or as all-consuming.

cherish as no other, a young lady who, after not seeing her for two months, I ached for in just about every way a young man could possibly ache for a woman. Now, in full candor I admit I since have known love that was maybe wiser, more stable and more mature than the love that wrapped itself around me that Friday as we headed down the Mass Pike toward Boston a lifetime ago. But as sure as I’m sitting here typing this, I promise you that the very moment this beautiful little pop single came on that car’s AM radio, and as I sat there alone in the back seat while two strangers I’d met on a ride board drove without speaking and turned onto Beacon Street – one part of my brain listening, while another overflowed with thoughts of Patti, with visions of her eyes, her smile, her voice, her smell and her touch darting through my head – I never had my heart fling more wide open, felt my skin tingle with any greater sense of anticipation, or experienced any emotion, before or since, as deep, as pure, as raw, or as all-consuming.

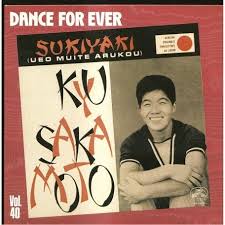

3. Sukiyaki

Kyu Sakamoto

1963

If they were to erect a statue in the cozy neighborhood of my youth to honor one of its favorite sons, it would not be in tribute to a politician, business leader, educator, or some historic figure. It would be of Ronnie Paxson, a mentally challenged man-child from the next block of Parsons Drive who in his time made a greater, deeper and more lasting impression on that little valley than all the politicians and business leaders combined. As a seemingly normal five-year old, Ronnie enrolled in Cherry Road School, only to have his parents and teachers soon notice his development wasn’t keeping pace with the others. As a result, he started going to a special school with a special bus, and in time grew into a gentle, loving giant with the mental capacity of (maybe) a six-year old, a trait that would define him for the rest of his life. But what made Ronnie Paxson a Westvale legend, beyond his gentle nature, his larger-than-life physicality and his ubiquitous presence, was his deep and abiding affinity for Top 40 radio. I had a sense why, but Ronnie’s parents always made sure their son had the latest in technology to accommodate what turned out to be his almost primal fascination with lyrics and melody. When we kids all started getting those cheap little pocket transistors from Japan, Ronnie would show up with a big AM/FM metal job encased in real leather and equipped with twin speakers and a handle. When the price of those came down to where our folks could actually

If they were to erect a statue in the cozy neighborhood of my youth to honor one of its favorite sons, it would not be in tribute to a politician, business leader, educator, or some historic figure. It would be of Ronnie Paxson, a mentally challenged man-child from the next block of Parsons Drive who in his time made a greater, deeper and more lasting impression on that little valley than all the politicians and business leaders combined. As a seemingly normal five-year old, Ronnie enrolled in Cherry Road School, only to have his parents and teachers soon notice his development wasn’t keeping pace with the others. As a result, he started going to a special school with a special bus, and in time grew into a gentle, loving giant with the mental capacity of (maybe) a six-year old, a trait that would define him for the rest of his life. But what made Ronnie Paxson a Westvale legend, beyond his gentle nature, his larger-than-life physicality and his ubiquitous presence, was his deep and abiding affinity for Top 40 radio. I had a sense why, but Ronnie’s parents always made sure their son had the latest in technology to accommodate what turned out to be his almost primal fascination with lyrics and melody. When we kids all started getting those cheap little pocket transistors from Japan, Ronnie would show up with a big AM/FM metal job encased in real leather and equipped with twin speakers and a handle. When the price of those came down to where our folks could actually  consider taking the plunge, Ronnie started carrying around an AM/FM/shortwave unit with untold bells and whistles, including, much to our disbelief, a cassette deck built right in. And so it went on through the rise of FM, the birth of the Walkman, the Boom Box era, the advent of the CD and, of course, the digital age. Ronnie showed us the way. But despite all that steady and regular change, in Westvale one thing remained constant: Ronnie Paxson. That’s why every few years he would watch as one group of friends left him and another came into his life, because every few years Westvale would produce a new crop of six year olds, and behold as yet another moved on to the next stage of development, leaving Ronnie, his gentle ways and his gadgetry in their rear view mirrors. I know this because I was part of Ronnie’s second wave of Westvale buddies. He was maybe 13 or 14 at the time. It was the fall of 1963, football season to be exact. The Beatles had yet to appear on Ed Sullivan, John Kennedy was still President, and some of the kids he entered Cherry Road with were playing a

consider taking the plunge, Ronnie started carrying around an AM/FM/shortwave unit with untold bells and whistles, including, much to our disbelief, a cassette deck built right in. And so it went on through the rise of FM, the birth of the Walkman, the Boom Box era, the advent of the CD and, of course, the digital age. Ronnie showed us the way. But despite all that steady and regular change, in Westvale one thing remained constant: Ronnie Paxson. That’s why every few years he would watch as one group of friends left him and another came into his life, because every few years Westvale would produce a new crop of six year olds, and behold as yet another moved on to the next stage of development, leaving Ronnie, his gentle ways and his gadgetry in their rear view mirrors. I know this because I was part of Ronnie’s second wave of Westvale buddies. He was maybe 13 or 14 at the time. It was the fall of 1963, football season to be exact. The Beatles had yet to appear on Ed Sullivan, John Kennedy was still President, and some of the kids he entered Cherry Road with were playing a  game of touch football. As Ronnie and I stood there on the Cherry Road playgound, me looking at the older kids, hoping one of them might get called home so I could fill in, and him probably wondering why his onetime classmates had closed him out of their lives, this song came on his big old GE radio. I would grow to love it over the years, in part because of its almost transcendent melody, but mostly because I would eventually learn its lyrics told the story of a man whose heart is broken, but who keeps his tears from falling by walking around with his head held high. I'll never forget that image. Nor will I’ll ever forget that cloudy, chilly afternoon in the fall of ‘63; just me, Ronnie Paxson and his ever-present radio. And when Sukiyaki began to play, we were both standing there watching from the sidelines. When it was over he looked straight ahead and without a trace of emotion or judgment said, “That’s a nice song.” To which I looked up at him and replied, “It sure is.”

game of touch football. As Ronnie and I stood there on the Cherry Road playgound, me looking at the older kids, hoping one of them might get called home so I could fill in, and him probably wondering why his onetime classmates had closed him out of their lives, this song came on his big old GE radio. I would grow to love it over the years, in part because of its almost transcendent melody, but mostly because I would eventually learn its lyrics told the story of a man whose heart is broken, but who keeps his tears from falling by walking around with his head held high. I'll never forget that image. Nor will I’ll ever forget that cloudy, chilly afternoon in the fall of ‘63; just me, Ronnie Paxson and his ever-present radio. And when Sukiyaki began to play, we were both standing there watching from the sidelines. When it was over he looked straight ahead and without a trace of emotion or judgment said, “That’s a nice song.” To which I looked up at him and replied, “It sure is.”

2. Can’t Get Used to Losing You

Andy Williams

1963

By now I hope you realize this exercise has never been about trying to be cool. It’s been about baring my soul and revealing, as honestly as I can, the songs, music and moments from ‘60s AM radio that touched me most and made the deepest, most lasting impression on me. Case in point; my second favorite 45 of the decade was not from the Stones, Beatles or Kinks, but a squeaky clean crooner from the far political right whose biggest claim to fame, besides his syrupy Christmas specials, cardigan sweaters and jillion-watt smiles, may have been the fact he discovered Donny Osmond. But this record blew me away when I first heard it, and the more I heard it, and the more I learned about it, the more it seared itself into my brain. The real star of Andy Williams’ incredible recording of Can’t Get Used to Losing You, you see, wasn’t Williams. It wasn’t even the fabled songwriting team of Doc Pomus and Mort Schuman, who at the time they wrote this one were coming off the blistering success of Viva Las Vegas. No, the real star of this magical recording was a largely unknown one-time Columbia in-house arranger named Robert Mersey, who took Pomus and Schuman’s melody and layered an entirely new one atop it, and in doing so created a pop masterpiece. Without drilling too deeply, let me just say that in music there’s a concept called legato, in

By now I hope you realize this exercise has never been about trying to be cool. It’s been about baring my soul and revealing, as honestly as I can, the songs, music and moments from ‘60s AM radio that touched me most and made the deepest, most lasting impression on me. Case in point; my second favorite 45 of the decade was not from the Stones, Beatles or Kinks, but a squeaky clean crooner from the far political right whose biggest claim to fame, besides his syrupy Christmas specials, cardigan sweaters and jillion-watt smiles, may have been the fact he discovered Donny Osmond. But this record blew me away when I first heard it, and the more I heard it, and the more I learned about it, the more it seared itself into my brain. The real star of Andy Williams’ incredible recording of Can’t Get Used to Losing You, you see, wasn’t Williams. It wasn’t even the fabled songwriting team of Doc Pomus and Mort Schuman, who at the time they wrote this one were coming off the blistering success of Viva Las Vegas. No, the real star of this magical recording was a largely unknown one-time Columbia in-house arranger named Robert Mersey, who took Pomus and Schuman’s melody and layered an entirely new one atop it, and in doing so created a pop masterpiece. Without drilling too deeply, let me just say that in music there’s a concept called legato, in  which notes are not sung or played with individual rests, but in which each note flows into the next, with no space between. Pizzicato, on the other hand, is a technique in which a stringed instrument is not swept or strummed, but pinched or popped with short plucks, a technique that creates a series of individual sounds yet still-connected notes. What Mersey did was have Williams sing the song’s primary melody, as written by Pomus and Schuman, legato-style, while beneath him, as a counter measure, a few violins played an entirely new melody pizzicato-style. The result was not unlike having two songs on the same side of the same 45 played simultaneously, with the listener free to choose which (or both) to follow. I remember it was New Year’s Eve. It was freezing cold and crystal clear that night, and I had just celebrated my ninth birthday just ten days earlier. On the radio, WOLF was counting down the Top 100 songs of 1963. President Kennedy was barely a month in the grave and the whole world had somehow, but in a meaningful way, changed forever. You could feel it. As I moved around the house, watched TV, played games, and listened to the hits of the year being counted down one by one, I grew restless, even – perhaps for the first time ever – a little nostalgic. Finally, not sure what to do with myself, and since my mom and dad were out at a party, I decided to take my sled to Westcott Reservoir, a gigantic man-made holding tank just up Salisbury Road, and a mountain of well manicured dirt and hard fill that rose high above

which notes are not sung or played with individual rests, but in which each note flows into the next, with no space between. Pizzicato, on the other hand, is a technique in which a stringed instrument is not swept or strummed, but pinched or popped with short plucks, a technique that creates a series of individual sounds yet still-connected notes. What Mersey did was have Williams sing the song’s primary melody, as written by Pomus and Schuman, legato-style, while beneath him, as a counter measure, a few violins played an entirely new melody pizzicato-style. The result was not unlike having two songs on the same side of the same 45 played simultaneously, with the listener free to choose which (or both) to follow. I remember it was New Year’s Eve. It was freezing cold and crystal clear that night, and I had just celebrated my ninth birthday just ten days earlier. On the radio, WOLF was counting down the Top 100 songs of 1963. President Kennedy was barely a month in the grave and the whole world had somehow, but in a meaningful way, changed forever. You could feel it. As I moved around the house, watched TV, played games, and listened to the hits of the year being counted down one by one, I grew restless, even – perhaps for the first time ever – a little nostalgic. Finally, not sure what to do with myself, and since my mom and dad were out at a party, I decided to take my sled to Westcott Reservoir, a gigantic man-made holding tank just up Salisbury Road, and a mountain of well manicured dirt and hard fill that rose high above  the neighborhood and from which a small boy could see for miles. I remember as my pack boots trudged through the crusty snow, this song began playing in my head, probably because it was the last one from the WOLF countdown I’d heard before setting out. I really don’t remember actually sledding that night. I only remember sitting atop the thing, the fog of my breath rising as I looked out over the lights of the city. It was peaceful, quiet and perfectly still as below me clocks throughout Syracuse struck midnight. Those pizzicato strings kept plucking in my head. Then, as 1963 slowly crossed over into history, and was replaced by 1964, even at nine years old I thought about the relentless, unforgiving nature of time and felt a gentle ache as it slowly passed, realizing for the very first time in my life I was powerless to stop it.

the neighborhood and from which a small boy could see for miles. I remember as my pack boots trudged through the crusty snow, this song began playing in my head, probably because it was the last one from the WOLF countdown I’d heard before setting out. I really don’t remember actually sledding that night. I only remember sitting atop the thing, the fog of my breath rising as I looked out over the lights of the city. It was peaceful, quiet and perfectly still as below me clocks throughout Syracuse struck midnight. Those pizzicato strings kept plucking in my head. Then, as 1963 slowly crossed over into history, and was replaced by 1964, even at nine years old I thought about the relentless, unforgiving nature of time and felt a gentle ache as it slowly passed, realizing for the very first time in my life I was powerless to stop it.

1. Five O’Clock World

Vogues

1966

It must almost seem a letdown, as I’m sure many are saying, “What? I slog through 300 singles, tiny specks of musical minutiae and deeply, overly personal anecdotes for this – an inconsequential and largely forgotten pop song by…the Vogues? Well, as I said, this exercise was never about being cool. It was about offering 300 tiny windows to my soul. And I can truly say this is my favorite pop 45 of the 1960s, if not all time. Oh, I suppose I could try to sell you on its merits. I could tell you Allen Jenkins, a Hall of Fame songwriter, who'd emerge as Garth Brooks’ personal producer, wrote it. I could tell you the record’s note-perfect instrumental track was produced in Nashville by some of that town's most sought-after sidemen, including the remarkable guitarist Chip Young. I could even tell you that, since he played on a number of the Vogues’ tracks, for years there'd been speculation the guy who laid down the stunning 12-string acoustic at the record’s outset was none other than Duane Allman himself. (It wasn’t. It was Young.) But rather than all that, let me just tell you this. This 45 means the world to me because it was the song I adopted as my very own end-of-the-day anthem when, after college, I moved to Chicago, scored my very first job, and became for the first time ever a full-fledged, train-riding, and paycheck-chasing working stiff. Oh, I'd tended bar for two years after school back home, but this was different. In 1979, when I somehow finagled my way into an entry-level gig with the White Sox, I was no longer just some grown up kid living with mom and dad in a now marginalized Rust Belt town. Suddenly I was in Oz, living in the heart of the City of Broad Shoulders, the City of Vote Early and Often, the City of Mayors named Daley and the City of "I got a guy." I was riding Chicago's storied el train to and from work, past landmarks like Wrigley Field and the Playboy Building

It must almost seem a letdown, as I’m sure many are saying, “What? I slog through 300 singles, tiny specks of musical minutiae and deeply, overly personal anecdotes for this – an inconsequential and largely forgotten pop song by…the Vogues? Well, as I said, this exercise was never about being cool. It was about offering 300 tiny windows to my soul. And I can truly say this is my favorite pop 45 of the 1960s, if not all time. Oh, I suppose I could try to sell you on its merits. I could tell you Allen Jenkins, a Hall of Fame songwriter, who'd emerge as Garth Brooks’ personal producer, wrote it. I could tell you the record’s note-perfect instrumental track was produced in Nashville by some of that town's most sought-after sidemen, including the remarkable guitarist Chip Young. I could even tell you that, since he played on a number of the Vogues’ tracks, for years there'd been speculation the guy who laid down the stunning 12-string acoustic at the record’s outset was none other than Duane Allman himself. (It wasn’t. It was Young.) But rather than all that, let me just tell you this. This 45 means the world to me because it was the song I adopted as my very own end-of-the-day anthem when, after college, I moved to Chicago, scored my very first job, and became for the first time ever a full-fledged, train-riding, and paycheck-chasing working stiff. Oh, I'd tended bar for two years after school back home, but this was different. In 1979, when I somehow finagled my way into an entry-level gig with the White Sox, I was no longer just some grown up kid living with mom and dad in a now marginalized Rust Belt town. Suddenly I was in Oz, living in the heart of the City of Broad Shoulders, the City of Vote Early and Often, the City of Mayors named Daley and the City of "I got a guy." I was riding Chicago's storied el train to and from work, past landmarks like Wrigley Field and the Playboy Building , rubbing elbows with some of the most famous, important and historic people in baseball. And I worked hard too, and for a staggeringly little money. But that little detail hardly mattered. I was in the big leagues. And I’m not talking about baseball. I’m talking about living and working in a big league city, making big league memories, and developing a big league network of friends and colleagues. So during the offseason, when we actually got to go home before midnight, this song would play in my head as I sat on the train and watched the city roll by. Because back then I was young and idealistic and truly “living on money that I ain’t made yet.” And back then, when a young beauty named Susie moved from Syracuse to be with me in Chicago, she became that “long haired girl who waits, I know, to ease my troubled mind." I don’t like it

, rubbing elbows with some of the most famous, important and historic people in baseball. And I worked hard too, and for a staggeringly little money. But that little detail hardly mattered. I was in the big leagues. And I’m not talking about baseball. I’m talking about living and working in a big league city, making big league memories, and developing a big league network of friends and colleagues. So during the offseason, when we actually got to go home before midnight, this song would play in my head as I sat on the train and watched the city roll by. Because back then I was young and idealistic and truly “living on money that I ain’t made yet.” And back then, when a young beauty named Susie moved from Syracuse to be with me in Chicago, she became that “long haired girl who waits, I know, to ease my troubled mind." I don’t like it  when critics call a pop song “perfect," but to me this record is as perfect as pop gets. When I think about its shimmering production and vocals, and the way it celebrates that brief sense of freedom at the end of every workday, it is the perfect song for a universally cherished moment – one that as a 24-year old I embraced with arms open. Yeah, it’s not the Beatles, Stones, or the Who. It’s the Vogues, for God’s sake, four doo-wop crooners from Pittsburgh. I get all that. But don’t kid yourself. This 45 is a more than just another oldie. Five O’Clock World by the Vogues, which went to #4 on the eve of the northeast's blizzard of ’66, is true art. It is pop art on a vinyl easel; pop art at its absolute finest; and pop art fully realized, exquisitely executed, and shamefully overlooked. But not by me. Thanks for sharing my list, my friends. Be well. And Godspeed.

when critics call a pop song “perfect," but to me this record is as perfect as pop gets. When I think about its shimmering production and vocals, and the way it celebrates that brief sense of freedom at the end of every workday, it is the perfect song for a universally cherished moment – one that as a 24-year old I embraced with arms open. Yeah, it’s not the Beatles, Stones, or the Who. It’s the Vogues, for God’s sake, four doo-wop crooners from Pittsburgh. I get all that. But don’t kid yourself. This 45 is a more than just another oldie. Five O’Clock World by the Vogues, which went to #4 on the eve of the northeast's blizzard of ’66, is true art. It is pop art on a vinyl easel; pop art at its absolute finest; and pop art fully realized, exquisitely executed, and shamefully overlooked. But not by me. Thanks for sharing my list, my friends. Be well. And Godspeed.