Greg Halman

Greg Halman

Sadly, every generation or so we must confront the grim reality that a handful of ballplayers will be taken from us before we ever get the chance to watch them fully realize their potential, not just as players, but people.

At this time six weeks ago, Greg Halman was a budding star in the Seattle Mariners’ system. A five-tool athlete and by all accounts a remarkable young man from (of all places) Holland, Halman was viciously and senselessly stabbed to death in a domestic dispute in his native country.

Intelligent and incredibly well-read, Halman spoke English and Dutch growing up, and then taught himself Spanish and Papiamento, the native language of Curacao, two languages he deemed necessary tools-of-the-trade for any modern-day ballplayer.

Blessed with great baseball instincts, Halman had also been recently trying to make up for lost time. As a native of the Netherlands, he had hit always left-handers well, but struggled against more advanced righties. He also had a tendency, especially early in his career, to strike out a high rate. But being a foreign-born player from a non-baseball land, he found himself a year or two behind many American players, and had been working hard to close the gap, something scouts felt he did in 2011.

Blessed with great baseball instincts, Halman had also been recently trying to make up for lost time. As a native of the Netherlands, he had hit always left-handers well, but struggled against more advanced righties. He also had a tendency, especially early in his career, to strike out a high rate. But being a foreign-born player from a non-baseball land, he found himself a year or two behind many American players, and had been working hard to close the gap, something scouts felt he did in 2011.

As a result, just a year after looking like a minor-league bust, he was called up in June by the M’s, and later that month belted his first major league HR against the Angels.

During the off-season, Halman returned to Holland to be with family, work-out, and continue conducting youth camps as a means of spreading the gospel of baseball to kids throughout Europe.

But this past November, while at home in the Rotterdam flat he shared with his brother, Halman got into an fight with his younger sibling – apparently himself a talented player, and a fellow member of the Dutch national team. In the fracas, Greg was slashed many times in the chest and neck, and bled to death on the scene.

But this past November, while at home in the Rotterdam flat he shared with his brother, Halman got into an fight with his younger sibling – apparently himself a talented player, and a fellow member of the Dutch national team. In the fracas, Greg was slashed many times in the chest and neck, and bled to death on the scene.

Only later did the details surrounding Greg Halman’s fatal stabbing begin to emerge, including the fact that the younger Halman had been suffering from what Greg had told family and friends was a growing number of “voices in his head.” For that reason Jason Halman remains today, not only in custody, but under around-the-clock psychiatric care.

Roy Hartsfield

Roy Hartsfield

The first-ever manager of the expansion Toronto Blue Jays in 1977, who took the job after spending 19 years in the Dodger organization, a number of them as Walter Alston’s right hand man.

Hideki Irabu

The guy who brought an air of uncertainty to Asian pitchers, something that flew in the face of what at the time had been a certain, almost beguiling sense of invincibility attached to pitchers from the Far East.

When the 6'4" half-Japanese/half-American Irabu first signed with the Yankees in 1997, the Dodgers’ Hideki Nomo (who won N.L. Rookie of the Year in '95) and Mac Suzuki of the Mariners (a highly prized minor-league prospect) were generally regarded as great young pitchers, potentially even dominant ones, and worthy of the hype being lavished upon them.

When the 6'4" half-Japanese/half-American Irabu first signed with the Yankees in 1997, the Dodgers’ Hideki Nomo (who won N.L. Rookie of the Year in '95) and Mac Suzuki of the Mariners (a highly prized minor-league prospect) were generally regarded as great young pitchers, potentially even dominant ones, and worthy of the hype being lavished upon them.

So when Irabu debuted at Yankee Stadium in July of that year, it was with a lot of pomp and circumstance, not to mention some very lofty expectations by many members of Pinstripe Nation.

But while he started out pretty well, it soon became clear that, unlike his Japanese contemporaries, particularly Nomo, Irabu was never going to be a great pitcher.

What’s more, to those who knew him best, he seemed to be carrying inside him some real personal demons; demons that, sadly, would manifest themselves more and more in his short and apparently deeply troubled life.

Infamously, in one spring training game he failed to cover first base on a routine grounder. An infuriated George Steinbrenner lashed out in the press, called his $12 million Japanese import a “fat pussy toad” and refused to let him travel on the team charter to Anaheim.

Infamously, in one spring training game he failed to cover first base on a routine grounder. An infuriated George Steinbrenner lashed out in the press, called his $12 million Japanese import a “fat pussy toad” and refused to let him travel on the team charter to Anaheim.

Steinbrenner eventually apologized, but the incident both scarred and branded the pitcher, particularly in the New York tabloids. What’s more, he would never really shake the condescension and lack of respect that seemed to emanate from Steinbrenner’s excessively graphic “fat pussy toad” comment.

Eventually traded to the Expos by, Irabu would a few years later find himself arrested for beating up a Japanese bar manager when his credit card was refused. By most accounts, the right-hander had consumed more than 20 drinks the night of the incident. Later still, he would be arrested in California and spend a few hours of sobering-up time in jail after being charged with DUI.

Eventually, Irabu would drink (and pitch) himself out of baseball, but not before trying to catch on one last time in 2009 with a small independent team as an aging, but still-physically imposing 40-year old.

Two years later, this July, police discovered the then-retired pitcher dead in his home near Los Angeles, the victim of an apparent suicide. Reportedly, his wife had recently informed Irabu that she and the couple’s two children were leaving him once and for all.

Two years later, this July, police discovered the then-retired pitcher dead in his home near Los Angeles, the victim of an apparent suicide. Reportedly, his wife had recently informed Irabu that she and the couple’s two children were leaving him once and for all.

An autopsy would reveal that, in keeping with his sad and often self-destructive history, Hideki Irabu was legally drunk at the time of his death.

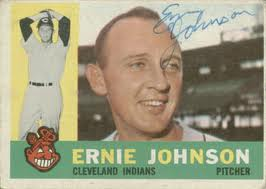

Ernie Johnson

Ernie Johnson

Most baseball fans know Milo Hamilton’s now-famous call in 1974 of Hall of Famer Hank Aaron taking the Dodgers’ Al Downing deep for his 715th career HR. What most don’t know is that, according to a handful of reports, the one-time Braves announcer – clearly hoping to leverage Aaron’s historic moment and to make a little history himself – had insisted to his long-time radio partner, the affable and easy-going Johnson, that as the big moment approached, the “voice of the team” should call every Aaron AB until such a time that the slugger broke Babe Ruth’s hallowed mark of 714 HR.

Whether the accounts of Hamilton’s self-serving request are true or not, to anyone who knew Ernie Johnson, the notion that he would step aside and let a colleague take the spotlight, even at his own expense, would come as no surprise at all.

Whether the accounts of Hamilton’s self-serving request are true or not, to anyone who knew Ernie Johnson, the notion that he would step aside and let a colleague take the spotlight, even at his own expense, would come as no surprise at all.

Forget that he had been with the organization on-and-off since 1942. Forget that as a young pitcher he had played in a couple of World Series for the team. And forget that, through hard work, practice and on-the-job training, he had transformed himself from just another ex-player behind the mic into a first-class and amazingly genial play-by-play man.

Ernie Johnson -- whose son now serves as studio host for NBA broadcasts on TNT -- might have been one of the most accommodating and selfless men to ever put on a baseball uniform or announce a big league game. And that simple fact always seemed to trump any urge he ever may have ever had for personal glory or self-promotion.

The Aaron situation was ironic, because less than a decade later on a Braves’ telecast on Ted Turner’s WTBS – a satellite-delivered local TV station whose national footprint in the ‘80s helped the once-hapless Braves briefly become “America’s Team” – Johnson made a thrilling and wonderfully in-the-moment home run call during another Braves-Dodgers contest. And it was a call that, to anyone who happened to hear it, stood toe-to-toe with Hamilton’s legendary call of Aaron’s blast.

One hot Saturday night in August of 1983, in front of a packed house of over 48,000 pennant-hungry, screaming fans in Atlanta, the division-leading Braves trailed the second-place Dodgers in the bottom of the 9th when pinch-hitter Bob Watson came off the bench and belted a 2-run shot off Steve Howe to propel his team to a stunning 8-7 win.

One hot Saturday night in August of 1983, in front of a packed house of over 48,000 pennant-hungry, screaming fans in Atlanta, the division-leading Braves trailed the second-place Dodgers in the bottom of the 9th when pinch-hitter Bob Watson came off the bench and belted a 2-run shot off Steve Howe to propel his team to a stunning 8-7 win.

Johnson’s animated, voice-cracking and ever-so-slightly Southern call of Watson’s game-winning blast and the euphoria it triggered in old Atlanta Fulton County Stadium, had it occurred during the World Series or under the bright lights of the MLB post-season, might have placed it among the finest moments in baseball broadcasting history.

And had it done so, fans everywhere might have had a chance, at long last, to recognize Ernie Johnson for what he truly was; one of the greatest play-by-play men of his generation, and one of the warmest, most comforting voices in baseball history.

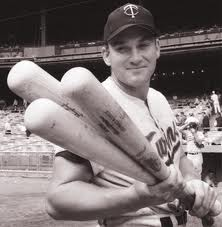

Harmon Killebrew

Harmon Killebrew

Before performance-enhancing drugs and band-box ballparks had conspired to destroy some of baseball’s host hallowed numbers and to greatly devalue its most storied hit – the HR – there was Harmon Killebrew.

Before there was a time when even middling hitters could break their bats or hit seemingly harmless pop flies and still reach the seats, there was Harmon Killebrew.

The owner of one of the most perfect right-hand swings in history, Killebrew used to stand staring out at the pitcher, perfectly straight and perfectly still, peeking behind a massive left bicep and ready at the blink of an eye to uncoil his potent bat and unleash his powerful, picture-perfect and slightly uppercut swing.

He wasn’t fast. He wasn’t big. And he certainly wasn’t mean. In fact, they called him Charmin’ Harmon. But he was strong. And he was was a hitter.

And not just any hitter, but a good old-fashioned a power hitter. A true, honest-to-god cleanup hitter. And when Killebrew’s bat exploded forward, his cheeks puffed out, and his left food extended on a line toward the pitcher, the balls he hit often arched skyward toward the seats with a grace that one could only describe as majestic.

Killebrew’s best year came in 1969, when he led the league with 49 HR and 140 RBI and was named the American League MVP.

Killebrew’s best year came in 1969, when he led the league with 49 HR and 140 RBI and was named the American League MVP.

But his most storied year might have been two years earlier in 1967, when his Twins, one of four American League teams locked in the single greatest pennant race in baseball history, fought down to the last weekend of the season before losing on the final day to the Red Sox.

For the year, Killebrew hit .269, while slugging 44 HR and 113 RBI.

Unfortunately for him, Boston’s Carl Yastrzemski chose the very same year to hit .326, with 44 HR and 121 RBI, the last time any player in either league won baseball’s coveted Triple Crown.

Even in retirement, Killebrew, who ranked third on the all-time HR list with career total of 573, found himself overshadowed by an odd combination of greatness and history. The year he was elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, who entered the Hall that very same year?

Hank Aaron.

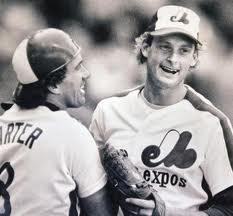

Charlie Lea

Charlie Lea

The only French-born pitcher to ever throw a no-hitter in the Major Leagues, and one of only three Montreal Expo pitchers in history to do so. Lea was yet another example of a pitcher whose promising career was cut far-too-short by injuries; in his case, season-ending, and eventually career-ending damage to both his pitching elbow and shoulder.

But not before he threw the above mentioned no-hitter in the strike season of '81 and also won an All Star game -- a pair of accomplishments only a handful of men who ever picked up a baseball can lay claim to.

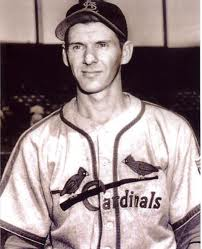

Marty Marion

Marty Marion

A former N.L. MVP who somehow continues to be both overrated and underrated by baseball historians, often at the same time.

To those who place stock in what contemporary sportswriters, opponents and teammates used to say about him, Marion was so incredibly great with the glove and so capable of turning the hardest and most unlikely plays into outs, some called him "Slats" or “The Octopus” for his tremendous range, arm and dependability at short.

But to a latter generation of number-crunchers and stat-heads who look at Marion’s largely pedestrian offensive production – including his numbers during his MVP season, when he hit .267, with 6 HR, 63 RBI, 50 runs and one stolen base – they scratch their heads and look upon the slick-fielding, eight-time All Star as, perhaps, the single most curious MVP choice in baseball history.

What’s interesting to note about Marion’s MVP season of ’44 is that that year he became the third of three different Cardinals to win the award in consecutive years, following teammates Mort Cooper and Stan Musial.

But more than that, it is important to remember that Marty Marion claimed the Most Valuable Player award in a year during which life in this country had been, literally, turned upside down by the war effort; named MVP at a time in American history when copper pennies were made of steel, when chocolate and nylon were as precious as gold, when factories were full of women, and when many of the best baseball players in the world were not doing what they normally did in summer, but overseas fighting for a cause they deemed far more crucial.

But more than that, it is important to remember that Marty Marion claimed the Most Valuable Player award in a year during which life in this country had been, literally, turned upside down by the war effort; named MVP at a time in American history when copper pennies were made of steel, when chocolate and nylon were as precious as gold, when factories were full of women, and when many of the best baseball players in the world were not doing what they normally did in summer, but overseas fighting for a cause they deemed far more crucial.

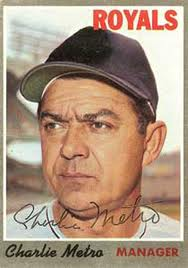

Charlie Metro

Charlie Metro

For the 1961 and '62 seasons, Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley announced one of the most bizarre experiments in baseball history. Rather than having a manager, his perennially woeful Cubs would be run by a “College of Coaches,” an eight-man committee comprised of eight coaches of equal standing, one of whom would be designated as “head coach.” Metro, the son of a Hungarian coal miner from Nanty Glo, Pennsylvania, who himself worked a couple of years in the mines, turned out to be the third of three such “head coaches” used by the Cubs during the ’62 season.

As a player, Metro (born Moreskonich) played for legendary managers Connie Mack and Casey Stengel, both of whom fell in love with his glove, arm and hustle. But because he couldn’t hit a lick, Metro eventually lost just about every starting job he was ever given in baseball, often before the season was over.

As a player, Metro (born Moreskonich) played for legendary managers Connie Mack and Casey Stengel, both of whom fell in love with his glove, arm and hustle. But because he couldn’t hit a lick, Metro eventually lost just about every starting job he was ever given in baseball, often before the season was over.

Much the same could be said of his brief managerial career. As one of the three “head coaches” of the ’62 Cubs, and as one of two guys to head up the hapless Royals of 1970, Metro’s record during his run as a big league skipper was an entirely forgettable 62-102.

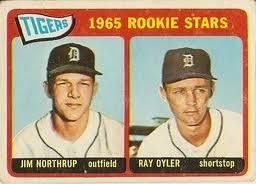

Jim Northrup

Jim Northrup

Nicknamed “The Silver Fox” for the color of his hair, Northrup had what might be called a “grand” season in 1968. Playing all three OF positions for the Tigers – part of manager Mayo Smith’s unique four-man platoon of Willie Horton, Al Kaline, Mickey Stanley and Northup – he hit a total of four grand slams that season, before hitting yet another one in the World Series.

On Monday, June 24th against the Indians, Northrup hit a grand slam in the 6th inning off Eddie Fisher, and then one in the 7th off Billy Rohr, making him at the time just the second player (after Jim Gentile) to hit a grand slam in consecutive at bats, and only the 13th to hit two in one game.

On Monday, June 24th against the Indians, Northrup hit a grand slam in the 6th inning off Eddie Fisher, and then one in the 7th off Billy Rohr, making him at the time just the second player (after Jim Gentile) to hit a grand slam in consecutive at bats, and only the 13th to hit two in one game.

Then on Saturday, June 29th against the White Sox, he connected off Cisco Carlos, making him the first and only player in baseball history to hit three grand slams in the same week.

Ironically, against the Tribe on the 24th and again against the White Sox on the 29th, he came up one more time with the bases loaded. In both instances, however, Northrup struck out.

But Jim Northrup’s biggest hit of that season was not a grand slam at all. In fact, it wasn’t even a homer.

But Jim Northrup’s biggest hit of that season was not a grand slam at all. In fact, it wasn’t even a homer.

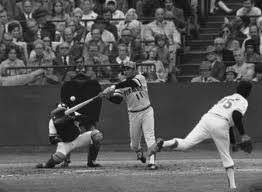

It came in Game Seven of the ’68 World Series against a fireballing right hander who, in that and two prior Series appearances, looked utterly invincible. Facing Bob Gibson (against whom he had homered in Game Four, giving the Tigers their only run against the Cardinal ace to that point), Northrup hit a line drive to CF that for just a sliver of a moment froze perennial Gold Glover winner Curt Flood, causing the ball to sail over his head for a triple. Northrup's scorching 7th innning line-drive scored both Norm Cash and Willie Horton, gave the Tigers the lead, stunned the Busch Stadium faithful, and caused the Fat Lady to start clearing her throat.

Bill Freehan then doubled the Breckenridge, Michigan native home with the run that proved to seal the deal for the Tigers, who at one point trailed in the Series 3-1.

Mickey Lolich deservedly won the World Series MVP Award for his three victories. But if not for Northrup and his stunning two-out, two-run triple, in the 7th inning of Game Seven, that honor likely would have gone to Gibson. And the odds are the Series, for the second year in a row (and the third time in five seasons), would have gone to the Cardinals.

On a personal note, I'd also like to add that many years ago, in 1964, Jim Northrup comprised one-third of the greatest minor league OF I have ever have ever seen in my life.

On a personal note, I'd also like to add that many years ago, in 1964, Jim Northrup comprised one-third of the greatest minor league OF I have ever have ever seen in my life.

Playing for my hometown Syracuse Chiefs and lining up in between two other future big league sluggers -- Horton in left and Mack Jones (on loan from the Milwaukee Braves) in right -- the three budding stars combined to tear apart that season what had been an otherwise pitching-rich International League.

Playing their home games in McArthur Stadium, whose CF fence was not only 434’ away from home plate, but nearly 20’ high, and facing many of the same pitchers who just a few years later would dominate Major League Baseball to the extent that the height of the pitching mound would have to be lowered – and playing without the benefit of a DH – the three sluggers combined to average .302, with 28 HR and 98 RBI per man over the course of a 154-game season.

Yes I was only nine. And yes it was just AAA. But I will go to my grave believing that, at least for one season, Jim Northrup, Willie Horton and Mack Jones were the single greatest minor league OF in my lifetime; if not the greatest, period.

Yes I was only nine. And yes it was just AAA. But I will go to my grave believing that, at least for one season, Jim Northrup, Willie Horton and Mack Jones were the single greatest minor league OF in my lifetime; if not the greatest, period.

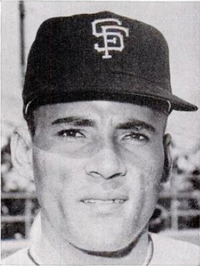

Jose Pagan

One of the oldest, most-critical and yet somehow ill-defined jobs in all of baseball is that of “utility infielder.” And in the 1960’s, there were few utility men anywhere any better than Jose Pagan, the starting SS for the World Series-bound San Francisco Giants in 1962, but a guy who -- except for that season and one other -- was a player whose job every year remained solely dependent on his ability to play just about every position, to play it well, and quite often, to play it at the drop of a hat.

Pagan was a versatile, good-hitting, utility infielder and pinch hitter for the perennially contending Giants at the beginning of the decade and a versatile, good-hitting, utility infielder and pinch hitter for the perennially contending Pirates at the close of it.

But before riding off into the sunset, Pagan got once last moment of glory, and one last chance to play October baseball.

But before riding off into the sunset, Pagan got once last moment of glory, and one last chance to play October baseball.

In Game Seven of the 1971 World Series, facing All Star lefty and 20 game winner Mike Cuellar, the Pirates’ Jack-of-All-Trades utility man came to bat in the 8th inning and laced a double into the right field corner that drove home Willie Stargell with the Bucs’ second and final run.

That second run -- and Pagan’s heroic RBI double -- ended up being the margin of victory as the Pirates squeezed out a hard-fought win and took the Series over Earl Weaver and his Baltimore Orioles, 2-1.

Part One of Three: more 2011 baseball deaths you may have missed.

Part Three of Three: more 2011 baseball deaths you may have missed.