He was born Nicholas Rodney Drake in 1948 in Rangoon, the formerly named capitol of the former British colony formerly known as Burma. And by the time he and his family had returned to their native England, most of his friends had taken to calling him simply, "Nick."

He was born Nicholas Rodney Drake in 1948 in Rangoon, the formerly named capitol of the former British colony formerly known as Burma. And by the time he and his family had returned to their native England, most of his friends had taken to calling him simply, "Nick."

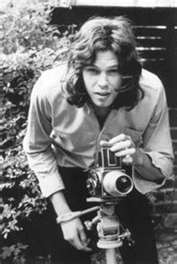

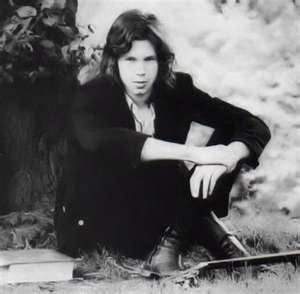

When Nick Drake was growing up a strapping young lad in a small, rural community about two hours north of London, it seemed there was little he couldn't do. He was tall, worldly, stunningly handsome, a remarkable lithe athlete and a natural born leader. He was also smart beyond comprehension and when in public seemed to draw attention from just about everyone, particularly women.

In short, Nick Drake was the classic Richard Cory character who, quite literally, "fluttered pulses" and "glittered when he walked."

But much like the seemingly perfect Cory in Edward Arlington Robinson's ironic poem, a larger than life figure who one night went home and put a "bullet through his head," the person a the center of the Nick Drake story was a tortured, tragic figure who no one could save from the cruel fate that awaited him.

Because at some point around the time the teenage Drake went to study at Cambridge University, the poised and confident young man started to change. And started to get sick. In fact, horribly and painfully sick.

Because at some point around the time the teenage Drake went to study at Cambridge University, the poised and confident young man started to change. And started to get sick. In fact, horribly and painfully sick.

And no, not the kind of sick that could have been treated with antibiotics or rest and relaxation. Or even an operation. Nick Drake's disease was one of his mind, and as a young man he grew more and more haunted by what today might be diagnosed as depression, paranoid schizophrenia or maybe even a bi-polar disorder.

Back then, however, many said he was simply a shy kid who had trouble sleeping and, most likely, suffered from insomnia.

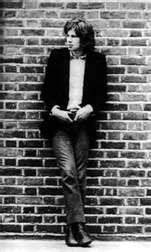

What Drake did learn during his three-year run at Cambridge is that he had an affinity for both playing and writing beautiful melodies. Slowly but surely he turned himself into a skilled (yet offbeat and entirely self-taught) guitarist whose ideas of tuning were all his own, and who'd practice for hours on end, all alone in the haunting quiet of his own room.

He also started writing songs. But Drake's songs weren't so much love songs or even songs of social awareness. His songs were often songs of loneliness and despair, songs of desperation, songs of melancholy and uncertainty. Songs that, despite their beauty, were hard to classify and often defied traditional notions of form and structure.

He also started writing songs. But Drake's songs weren't so much love songs or even songs of social awareness. His songs were often songs of loneliness and despair, songs of desperation, songs of melancholy and uncertainty. Songs that, despite their beauty, were hard to classify and often defied traditional notions of form and structure.

And they were written by a songwriter being driven mad by his personal demons, a young man who seemed less capable of actually living life than observing it from afar. As Rolling Stone's Anthony DeCurtis once wrote about Drake, it's "as if he were viewing his life from a great, unbridgeable distance."

One day the bass player for the British folk/rock group Fairport Convention saw Drake playing in a small pub in Camden Town and was blown away. Not only was Drake tall and breathtakingly handsome, could play brilliantly and sing like an earth-bound angel, but, in the words of Ashley Hutchings, "He looked like a star. He looked wonderful. He seemed to be 7' tall."

Hutchings soon introduced the shy and retiring Drake to a bold and aggressive 25-year old American ex-pat from Boston, Joe Boyd, who was trying to make a name for himself in London as a rock manager and record producer. Boyd listened to some tapes of Drake and sensed the kid was, indeed, something special. It was 1968.

Hutchings soon introduced the shy and retiring Drake to a bold and aggressive 25-year old American ex-pat from Boston, Joe Boyd, who was trying to make a name for himself in London as a rock manager and record producer. Boyd listened to some tapes of Drake and sensed the kid was, indeed, something special. It was 1968.

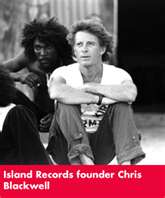

Boyd eventually cut a deal with Chris Blackwell, the founder of Island Records. Blackwell, who'd personally find and sign such rock icons as Stevie Winwood, Cat Stevens, Bob Marley and U2, went crazy over Drake and unlike perhaps even Boyd himself, really thought he had it in him to become a superstar.

That's why Blackwell gave Boyd an almost unheard of clause in Drake's contract, one which stated that none of the records that the young man did for Island would ever go out of print.

That's why Blackwell gave Boyd an almost unheard of clause in Drake's contract, one which stated that none of the records that the young man did for Island would ever go out of print.

What Blackwell didn't know was the extent of the demons that haunted Drake, particularly at night. Nor did he know the depth of his insecurity or how fragile his new singer/songwriter's psyche really was.

That's why with each of the three albums Drake did for Island Records he became increasingly distant and difficult to reach. That's why following the first album he recorded, he started pulling back from touring and performing live. And why after the second, he refused many press interviews and publicity opportunities.

And that's why the third and last of the three albums actually showed up one day in the form of a single reel-to-reel tape, stuffed unadorned in a brown envelope and delivered to the receptionist's at Island, where it sat for a few days before being discovered.

And that's why the third and last of the three albums actually showed up one day in the form of a single reel-to-reel tape, stuffed unadorned in a brown envelope and delivered to the receptionist's at Island, where it sat for a few days before being discovered.

On the front of the envelope were hand-written the name of the artist, "Nick Drake" and the name of the album "Pink Moon."

By this point, the Island A&R people -- unaware of Drake's increasingly disabling mental disorder -- had had enough. They were tired of his pathological shyness and his unwillingness to promote his records, tired of his steadfast refusal to perform in public, and ultimately, tired of his records' inability to sell. In fact, if they had their way he would have been fired. But Blackwell was adamant and continued to believe in him.

When Pink Moon was finally polished up and mixed, per their agreement, Island Records released it. But despite Blackwell's exuberance, the publicity department accompanied its release with a somewhat caustic press release that read in part: "His first two albums haven't sold a shit. But if we carry on releasing them, then perhaps someone authoratative [sic] will stop, listen properly and agree with us."

At that point Drake had become consumed by his thoughts, his loneliness and his melancholy over having failed so miserably as a musician. He could no longer be around strangers, and according to a story years later in the London Observer, only seemed to take comfort in driving for long distances out in the country, all by himself.

At that point Drake had become consumed by his thoughts, his loneliness and his melancholy over having failed so miserably as a musician. He could no longer be around strangers, and according to a story years later in the London Observer, only seemed to take comfort in driving for long distances out in the country, all by himself.

What's more, this reality became apparent: the most any one of this three albums ever sold was a mere 5,000 copies. An absolute pittance, especially before the days when the Internet, streaming and the indy movement completely splintered the marketplace.

Drake eventually moved back home with his parents, a move he hated, but one he knew he needed to make in order to somehow try to survive. His parents, who loved him desperately, tried all they could, but in the end it was no use.

Nick Drake's beautiful, gentle, fiercely independent and wildly creative mind was simply too broken to fix, and early on the morning of November 25, 1974, following yet another night of sleeplessness, restless pacing and late-night bowls of cereal, his mother found his long, lanky, lifeless body sprawled across his unassuming single bed, dead of an overdose of an anti-psychotic drug he had been taking.

And that might have been it, and the world may have completely forgotten Nick Drake, except for a handful of random events.

In 1977, Blackwell hired as the head of his publicity department the former editor at Melody Maker, a music-loving and imaginative free-thinker named Rob Partridge. Partridge, who would use his press savvy that very same year to transform Bob Marley into an international star for Island, and who would later pull Blackwell kicking and screaming to a pub in the south of London to hear a band he he'd just seen -- a band calling themselves U2 -- had always been a huge fan of Drake.

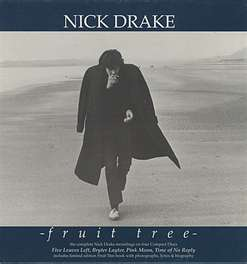

Partridge had seen Drake in a small club in 1969 and had loved his beautiful, haunting and slightly off-center music ever since. That's why just a few years after he came on board, he urged Island to release a box set of all Drake's material, and include unreleased photos and a comprehensive biography of the singer. The collection, named after a Drake song, was called Fruit Tree.

Just like Drake's original albums, Fruit Tree didn't sell a lick. But because it was supported by Partridge's record industry know-how and traded on many of his old contacts in the music press, the critics took a second look at Nick Drake. And this time, perhaps in light of his tragic demise, they were much more open to his music than they'd been just a few years earlier.

Just like Drake's original albums, Fruit Tree didn't sell a lick. But because it was supported by Partridge's record industry know-how and traded on many of his old contacts in the music press, the critics took a second look at Nick Drake. And this time, perhaps in light of his tragic demise, they were much more open to his music than they'd been just a few years earlier.

This time the critics actually heard Nick Drake, and many truly came to realize just how much they'd missed the first time around.

What's more, since his albums were all still in print, it was not necessary to scour the cut-out bins to find them. They were still available from the Island catalog and in record stores in countries all over the world.

As a result, Drake not only became a critical darling, in a very real way he very much stayed alive. And on top of that, it was suddenly cool in many prestigious and influential circles to actually like him., and to say you liked him.

Nick Drake, in other words, had something in death he never had going for him in life: momentum.

Nick Drake, in other words, had something in death he never had going for him in life: momentum.

And it continued throughout the 80's, as more and more artists began to rise up and acknowledge Drake's influence on their music.

Robert Smith of the post-punk group, the Cure, admitted he named his band after Drake's song, Time Has Told Me ("a troubled cure for a troubled mind").

Legendary British folk singer and guitarist John Martyn said that he wrote the title track for his seminal album, Solid Air, for and about Drake.

Mike Mills and Michael Stipe of R.E.M. spoke of Drake's profound influence on them during the making of 1985's Fables of the Reconstruction, which was recorded in England and produced by Drake's former producer, Boyd.

And in that same year, the Dream Academy, an otherwise forgettable British pop group, released Life in a Northern Town, which became something of an international sensation for the band. The single, perhaps named in honor of the part of England the singer called home, included both an on-sleeve tribute to Drake's memory and the following words from the song's final verse:

The evening had turned to rain

Watch the water roll down the drain,

And we followed him down to the station.

Though he never would wave goodbye,

You could see it written in his eyes

As the train rolled out of sight.

Bye-bye.

But Nick Drake's true vindication as an artist would still be 15 years away.

Finally, in 1999, the Boston-based advertising agency, Arnold Worldwide, was busy putting the final touches on an innovative new campaign they had created for the 2000 Volkswagen Cabriolet, with its tagline, "Drivers wanted."

One of the campaign's first TV ads was all but done. It was storyboarded, shot, and named. The creative director at the agency decided to call it "Milky Way," since the plan was to use the Church's 1989 hit from Australia, Under the Milky Way, as the soundtrack.

One of the campaign's first TV ads was all but done. It was storyboarded, shot, and named. The creative director at the agency decided to call it "Milky Way," since the plan was to use the Church's 1989 hit from Australia, Under the Milky Way, as the soundtrack.

The premise of the ad was four kids are driving in their Cabrio headed for a party one dark and beautiful moonlit night. The kids drive in silence, the car's convertible top down, exposing a rich, full moon in the cloudless sky. When they get to the party, they see it is just more of the same; same faces, same talk, same old tired thing.

So without saying a word, they simply look at each other. The driver then puts the car in reverse, backs away, and without ever turning off the engine, drives his passengers into the quiet and unknown wonder of the still-moonlit night.

As the agency's creative team watched the shimmering, eerie stillness of the visuals and listened to the compelling but too-familiar music playing underneath, one person in the room suddenly had an idea. He remembered an album he had in his record collection at home. It was called Fruit Tree, a vinyl compilation of Nick Drake songs someone had once given him. He urged the team before they went into final production to take at least one listen to a song he had in mind.

As the agency's creative team watched the shimmering, eerie stillness of the visuals and listened to the compelling but too-familiar music playing underneath, one person in the room suddenly had an idea. He remembered an album he had in his record collection at home. It was called Fruit Tree, a vinyl compilation of Nick Drake songs someone had once given him. He urged the team before they went into final production to take at least one listen to a song he had in mind.

The next day he brought in the record for the team and played that one song, Pink Moon, along with a version of the ad without an audio track.

When it was over the creative director, his eyes wide and his mouth open, looked at the member of his team who brought in the record and asked simply, "My god, who is that?"

"That," said the guy standing next to the vintage turntable, "is Nick Drake."

And that's how it happened for Nick Drake.

Arnold's Cabrio spot -- launched under its original name, "Milky Way" -- became a cultural phenomenon in 2000. And people all over began wanting to know all about both the singer and the song in the otherworldly new VW ad.

As a result, the all-but-unknown Nick Drake sold more records in one month of 2000 than he had the previous 30 years...combined.

Literally overnight, he became a phenomenon, and by the end of 2000 had risen to become the 5th largest-selling artist on Amazon.

All of this came too late for Nick Drake, of course, but not for his mother, Molly, and sister, Gabrielle, both of whom were there for Nick in the tough times, and each of whom took a measure of solace, even comfort, in his unexpected fame.

All of this came too late for Nick Drake, of course, but not for his mother, Molly, and sister, Gabrielle, both of whom were there for Nick in the tough times, and each of whom took a measure of solace, even comfort, in his unexpected fame.

For Gabrielle, a successful actor in her own right, her little brother's suffering was not in vain. He'd lived with her briefly while recording his first album, and she recalled one time him telling her that if his music touched even one person, it would be worth it. As he told her, "If only I could feel that my music had ever helped anyone in any way, I would feel better.”

Years later, she related to a writer how, long after his death, fans would still come to the house to visit where her little brother had lived and died. She said it would mean a great deal to her parents, particularly when one young fan told Nick's mother how her son's songs had saved his life.

He told Molly Drake that he would have been just like Nick, and would have ended up killing himself. Yet, he found meaning and reason in Nick's lyrics and melodies, and it was his music that helped him fight through his own personal hell.

He told Molly Drake that he would have been just like Nick, and would have ended up killing himself. Yet, he found meaning and reason in Nick's lyrics and melodies, and it was his music that helped him fight through his own personal hell.

That meant a great deal to her mother, said Gabrielle Drake, and just like he had told her years ago, it would have also helped make the pain and suffering somehow all worth it to Nick.

Why do people love Drake now, like they never did before? Tough to say, but it's possible that we as a public need certain tortured souls to be martyrs before we're willing to embrace them as artists.

Maybe we love Nick Drake as much for what he was, as what he might have someday become; as much for the beautiful ballads he left behind as all the gentle, soulful music he might have one day made.

Or maybe, like Van Gogh, we needed a safe distance from him and his pain, and found it easier to focus on the young man's passion, or better yet, the art that his pain and passion made possible.

Regardless, few tales of posthumous acclaim touch the soul or seem so bittersweet as the story of Nick Drake.

Regardless, few tales of posthumous acclaim touch the soul or seem so bittersweet as the story of Nick Drake.

There are any number of Nick Drake songs that might be worth showcasing here. But if you are going to start with one, you might just as well choose Northern Sky. It is a song from Drake's second album, Bryter Layter, released in 1970.

It is a song that features some stunningly beautiful piano work by John Cale, the Welshman who had helped form the Velvet Underground just a few years earlier with iconic rocker Lou Reed.

But perhaps more than anything, it is the single most positive and loving song in Nick Drake's canon. A song that speaks of hope, trust and the need for the healing power of someone special. And a song that -- like Molly Drake once said of her son, "I think he wrote the nicest melodies early in the morning" -- is beautiful in a way that is difficult to put into words.

But perhaps more than anything, it is the single most positive and loving song in Nick Drake's canon. A song that speaks of hope, trust and the need for the healing power of someone special. And a song that -- like Molly Drake once said of her son, "I think he wrote the nicest melodies early in the morning" -- is beautiful in a way that is difficult to put into words.

With that, here is M.C. Antil's Song of the Day for November 25, 2011 -- 37 years to the day after he left us -- a hopeful, loving and gentle plea by a young man to someone he holds dear, a song probably written in the early dawn one morning after yet another long and troubled night, and one that the British magazine NME once dubbed simply, "the greatest English love song of modern times."

Nick Drake's Northern Sky.