Author's note: This is a rather long-winded tribute to a recently-fallen idol. So consider this brief caveat, if you will, my geek alert. If you're a Steely Dan nut, as I; indeed, read on. You may actually enjoy the ride. But if you've never been baptised in the cool, healing waters of Walter Becker and Donald Fagan's unique and often unlikely marriage of words and music, then, as an officer might say to gapers at an accident scene, "Move along, folks. Nothing to see here."

Author's note: This is a rather long-winded tribute to a recently-fallen idol. So consider this brief caveat, if you will, my geek alert. If you're a Steely Dan nut, as I; indeed, read on. You may actually enjoy the ride. But if you've never been baptised in the cool, healing waters of Walter Becker and Donald Fagan's unique and often unlikely marriage of words and music, then, as an officer might say to gapers at an accident scene, "Move along, folks. Nothing to see here."

From a layman's perspective at least, yours truly is a guitar geek of the first magnitude. Grew up loving the six-string from almost the first time I heard it. Don’t play it at all, mind you. Just adore the ever-loving crap out of it.

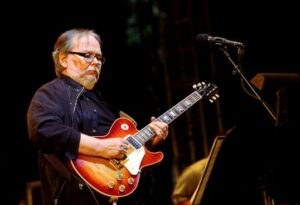

![]() In the hands of an artist, the sound of a well-made and well-tuned guitar -- especially one electrified and routed through a speaker with just enough hair on it to get the job done -- can send bolts of lightning through a room, particularly when that room (whatever its size, shape or even smell) is full of kindred spirits, fellow travelers, and lovers of bending, wailing and every-so-often weeping guitar strings.

In the hands of an artist, the sound of a well-made and well-tuned guitar -- especially one electrified and routed through a speaker with just enough hair on it to get the job done -- can send bolts of lightning through a room, particularly when that room (whatever its size, shape or even smell) is full of kindred spirits, fellow travelers, and lovers of bending, wailing and every-so-often weeping guitar strings.

That’s why I guess I fell so head-over-heels in love with Steely Dan back in the day. Because two guys named Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, along with the ambitious band they started, came into my life right as my own personal odyssey was hurdling headlong from musical adolescence to musical adulthood.

Or at least, I should say, that’s why I so fell in love with the first incarnation of Becker and Fagen’s band. Because the Steely Dan of my salad days was not one, but two different bands.

Though not “two bands” in the way many might have heard or even now expect...

Not “two bands,” for example, like the Can’t But a Thrill/traditional first album/touring-and-road-weary Steely Dan that just a year or two later would morph into the sardonic, whip-smart and studio-bound Steely Dan.

Not even “two bands,” as in the Steely Dan that in its prime almost single-handedly rewrote the language of pop music, and the Steely Dan that rose from the ashes after Becker and Fagen, who’d been estranged for years, reunited for a victory lap.

No, I’m talking about the two Steely Dans that existed at the very peak of Becker and Fagen’s considerable powers as music makers.

No, I’m talking about the two Steely Dans that existed at the very peak of Becker and Fagen’s considerable powers as music makers.

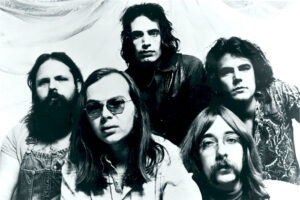

At first, the duo’s brainchild, an FM staple during the AOR-fueled 70's, was a band – like even the rawest garage bands – whose songs were firmly (and even religiously) constructed around the guitar.

Then, after four or five guitar-laden and solo-rich albums, that Steely Dan morphed into a slightly modified (but fundamentally different) version of its former self; a Steely Dan that still traded heavily on tasty guitar licks, but one that conspicuously nudged its lead instrument to the side so it might share center stage with the likes of the keyboards and horns.

And in the process, something happened to the Steely Dan I’d always known and loved. Becker and Fagen’s band (one named, as many know, after a literary dildo) transformed from a rock band with jazz overtones to a jazz band with its impulses, attitude and lyrics still squarely rooted in glorious rock and roll.

I bring this up because today I wish to pay my long-overdue respects to a musician – a man, really – who influenced my taste in (and, I guess, expectations for) pop music as much as any in my life; an artist who, my sense is, was the true architect behind Steely Dan’s early guitar sound.

I bring this up because today I wish to pay my long-overdue respects to a musician – a man, really – who influenced my taste in (and, I guess, expectations for) pop music as much as any in my life; an artist who, my sense is, was the true architect behind Steely Dan’s early guitar sound.

Walter Becker, guitarist, bassist, irascible cynic, recovering hellion, jazz lover and historian, devoted father, and one of the most brilliant, publicity-shy and enigmatic figures in rock history, died of cancer two weeks ago at his home in Hawaii.

And as he passed, he left this world with an IOU of mine still buried somewhere deep inside his pocket. Because, from the bottom of my heart, and almost from Day One, I owed Walter Becker a debt that I remain, now and forevermore, incapable of repaying – though throughout the years, Lord knows I’ve tried; in conversation with others, in my musical purchases, and, at least in part, in the very blog you’re reading now.

Let me explain.

It was 1977, 40 years ago this very time of the year. I was about to sign the lease on my first post-college apartment and had spent weeks scouring my folks’ house and the local Goodwill stores for used furniture, lamps, wall hangings, and any other knickknacks and doo-dads that might help my new place feel more like home.

But then, on the Saturday night before my roommate and I were set to move in, I went out to a high-end audio store and purchased the one-and-only, brand-spanking new, fresh-from-the-box accessory I would buy for my new home; a state-of-the-art analog stereo system.

But then, on the Saturday night before my roommate and I were set to move in, I went out to a high-end audio store and purchased the one-and-only, brand-spanking new, fresh-from-the-box accessory I would buy for my new home; a state-of-the-art analog stereo system.

Yet, whaddya know? Because I’d spent so much on that Ponderosa-sized mix of electronics and killer turntable, I only had a few bucks left to buy, you know, records to play on it – just enough, in fact, for a single LP.

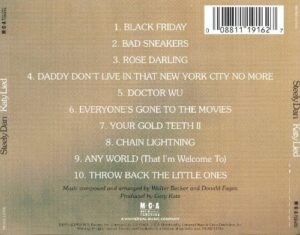

And for reasons that still escape me, that one album I chose to take home with me that crisp late-summer night was Steely Dan’s Katy Lied.

Now, look, I’ll be honest. Katy Lied is not Becker and Fagen’s strongest effort. But don’t kid yourself, to my still-fomenting ear, not to mention my cement-fresh and deeply impressionable young mind, it was nothing less than a gateway drug.

Thanks to Katy Lied, one listen and the world of a rudderless, if not clueless, college kid became a bigger, far more textured, and infinitely more ambiguous place. And I may not have know much at the time, but I sure as hell knew I wanted to know more.

Before I could help myself, Katy Lied had led me to Countdown to Ecstasy, which in turn led me to Pretzel Logic, which, of course, then led me to The Royal Scam. Not a chronological sequence of Steely Dan releases, but a musical one at any rate.

Before I could help myself, Katy Lied had led me to Countdown to Ecstasy, which in turn led me to Pretzel Logic, which, of course, then led me to The Royal Scam. Not a chronological sequence of Steely Dan releases, but a musical one at any rate.

(Eventually, I went out and bought the first album, Can't Buy a Thrill, as well. But, truth be told, as terrific an album as it was, I took one listen and never really played it, at least in its entirety, again.)

It was in those first four Steely Dan albums of mine that would serve as the four vinyl pillars of my listening for the foreseeable future; the four aural prisms, if you will, I’d take out every day, hold up to the sunlight, and watch as my little apartment was filled, as if by magic, with a virtual sea of brilliant, complex and ever-shifting musical shapes and colors.

That’s also why for the next two years, night after night after bartending and hustling for tips, I’d come home, open a beer, twist one up, and find myself transported to an entirely different world than the one I’d been led to believe was out there; a  sometimes lawless and borderless place populated by losers, loners, ladies of the night, social outcasts, sexual outsiders, and even a meek bookkeeper’s son who’d done some unspeakable wrong and a post-apocalyptic ham radio operator hell-bent on some level of human contact – a rogues gallery, if you will, of fringy characters and survivors of life’s battles, all of them made not just real, but oddly sympathetic, by Becker and Fagan’s unique blend of lyrical dexterity, harmonic sophistication, and, of course, guitar brilliance.

sometimes lawless and borderless place populated by losers, loners, ladies of the night, social outcasts, sexual outsiders, and even a meek bookkeeper’s son who’d done some unspeakable wrong and a post-apocalyptic ham radio operator hell-bent on some level of human contact – a rogues gallery, if you will, of fringy characters and survivors of life’s battles, all of them made not just real, but oddly sympathetic, by Becker and Fagan’s unique blend of lyrical dexterity, harmonic sophistication, and, of course, guitar brilliance.

But then came Steely Dan’s next release, Aja, an album that was a monster in every way possible; indeed, the most commercially viable, radio-friendly, and critically lauded album the two would ever release.

What’s more, for a pair of legendary (if not anal) perfectionists, whose insistence on take after take to achieve even a half-moment of recorded perfection, Aja had a sound so shimmering and crisp that to this day it remains a landmark, even by Becker and Fagen’s lofty standards for studio polish.

The only problem, at least for me, was that Aja’s sound was fundamentally different from my core-four gems, Katy Lied, Countdown to Ecstasy, The Royal Scam and Pretzel Logic.

The only problem, at least for me, was that Aja’s sound was fundamentally different from my core-four gems, Katy Lied, Countdown to Ecstasy, The Royal Scam and Pretzel Logic.

The guitar – particularly that instrument’s tastefully understated but occasionally blistering solos – the bedrock upon which the other Steely Dan albums four were built, was not nearly so prominent in the jazz-and-hook laden Aja.

All the other trademark elements were there, of course. But the parade of guitarists that Becker and Fagen employed in the making of Aja found themselves, for the first time in Steely Dan's brief but glorious run, being asked to share top billing with the keyboardists, horn players and even percussionists they likewise hired.

With Aja, Steely Dan took a giant step toward a more integrated and sophisticated form of music – a change in which their still-wonderful songs took on the harmonic structure and arrangements less of three-chord rockers than Big Band-era jazz standards. And while I admired and maybe even liked the change, it made me sad to think that Becker and Fagen had moved on and left the Steely Dan I so loved in their rearview mirrors.

What’s more, knowing what little I did of the two, I got the strong sense neither would likely return anytime soon to the ground they’d cultivated so richly, so devilishly and so magnificently.

Which brings me back to Walter Becker.

* * * * *

Only recently did I learn of the extent of Becker’s drug addiction and his many physical and personal problems around the time of The Royal Scam and Aja. And if you listen carefully to either, you can almost hear Becker, a guitarist by nature, retreating ever-so-slightly into a secondary role with Steely Dan, while Fagen, a keyboardist, assumes more control over its sound and direction.

Only recently did I learn of the extent of Becker’s drug addiction and his many physical and personal problems around the time of The Royal Scam and Aja. And if you listen carefully to either, you can almost hear Becker, a guitarist by nature, retreating ever-so-slightly into a secondary role with Steely Dan, while Fagen, a keyboardist, assumes more control over its sound and direction.

Don’t get me wrong. It doesn’t feel like there was a palace coup within Steely Dan. It just seems (or, more to the point, sounds) like one of the partners has stepped up as his old college buddy and musical soul mate finds himself in a life-and-death struggle with his many personal demons.

(And that theory is only supported if one listens to either Gaucho or Fagen’s first solo effort, The Nightfly, both of which came not long after Aja, and both of which further the immersion of the guitar, while accentuating the keyboards and horns.)

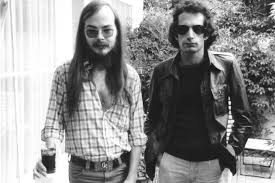

John Lennon once said that in the early days of the Beatles he and Paul McCartney used to write songs “eyeball to eyeball.” As great a songwriting team as Walter Becker and Donald Fagen were, I never pictured them as “eyeball to eyeball.”

I always imagined their music-making more a “shoulder to shoulder” exercise; both men sitting at the piano or the mixing board like wide-eyed, impish, but still mad scientists, fine tuning every last detail of a song, however minute, while just beyond the glass some of the finest pop instrumentalists of the 20th Century helped them transform their symphonic, note-specific, and gently twisted world-view into a brand of music the likes of which no one had ever heard before.

I always imagined their music-making more a “shoulder to shoulder” exercise; both men sitting at the piano or the mixing board like wide-eyed, impish, but still mad scientists, fine tuning every last detail of a song, however minute, while just beyond the glass some of the finest pop instrumentalists of the 20th Century helped them transform their symphonic, note-specific, and gently twisted world-view into a brand of music the likes of which no one had ever heard before.

But of the two, I always felt it was Becker, while apparently not as droll or caustic as Fagen, who brought a dark, ominous and even a tad frightened sensibility to Steely Dan’s quixotic lyrics. And, especially if you listen to The Nightfly, which is entirely Fagen and largely free of innuendo, mischief-making and foreboding imagery, you get the sense that it was likely Becker who added so much of those things to Steely Dan’s earliest and edgiest song lyrics.

That’s an idea even Fagen indirectly supported when he was interviewed the day of Becker’s death, a cryptic sentiment that said something to the effect that much of his dear partner’s art and wry humor was shaped by his rather difficult upbringing.

That’s an idea even Fagen indirectly supported when he was interviewed the day of Becker’s death, a cryptic sentiment that said something to the effect that much of his dear partner’s art and wry humor was shaped by his rather difficult upbringing.

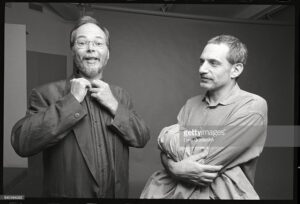

Indeed, I was at Tower Records on New York’s Upper West Side once around the turn of the century, and having cup of coffee and reading the paper in the store’s coffee shop. I remember as I looked up from my New York Times, I saw sitting there directly across from me Walter Becker and some age-appropriate lady I assumed to be either his wife or girlfriend.

Now, understand, true New Yorkers never – and I mean never – acknowledge celebrity, even when in the presence of those most deserving of it. It’s simply just not done. My sense is that’s why so many public figures choose to live there. The unwashed masses simply go about their days and mill about them, often without even glancing, acting as though that person, however famous, is just one more rat in the magnificent maze they call home.

And that impulse, to simply look the other way and go on with my day, was fighting me for all it was worth as I sat there gauging whether or not to go up, extend my hand, and thank Becker for his music and what, in particular, his four guitar-driven albums meant to me.

But even as I sat there, I saw the man and how he and his partner were interacting – or should I say not interacting? Because there was a tension so thick between the two, and a mood so icy, it was almost as though each was on his or her own planet.

But even as I sat there, I saw the man and how he and his partner were interacting – or should I say not interacting? Because there was a tension so thick between the two, and a mood so icy, it was almost as though each was on his or her own planet.

I quickly thought better of it, and never gave approaching Becker another thought. I simply took a sip of coffee, shook my paper, cleared my throat, and went back to reading my Times.

So when I heard that Walter Becker had died a few days ago, that memory – that moment – in Tower Records was the first thing that popped into my head.

But it wasn’t the only thing. Here’s what also did.

It was a song; a song off, of all albums, Aja. Not the biggest Steely Dan song, mind you, much less the best. And, frankly, it was a Steely Dan song that until that morning I’d never given a whole lot of thought to, one way or another.

But for some reason or another I just could not get the damn thing out of my mind when I first heard that Becker, one of my flesh-and-blood musical heroes, had passed. And that was especially true of the first couplet in the song’s chorus.

But for some reason or another I just could not get the damn thing out of my mind when I first heard that Becker, one of my flesh-and-blood musical heroes, had passed. And that was especially true of the first couplet in the song’s chorus.

The song that crawled into my brain and held on for dear life was the wonderful but largely overlooked, Home at Last – a song that I'd long considered an almost throwaway tune on Aja and one that, ironically, features one of the relatively few Steely Dan guitar solos that Becker actually played himself.

And here’s the couplet/ear bug that worked its way into my brain and refused to let go:

Now the danger on the rocks is surely passed, still I remain tied to the mast.

Could it be that I have found my home at last? Home at last?

Anyone familiar with the Odyssey and the epic story of Odysseus, the sirens, and the warrior’s 15-year sojourn to return to his beloved Ithaca, knows exactly what Becker and Fagan were referring to when they wrote of being “tied to the mast.”

In Homer’s saga, the sirens were beautiful women whose exotic songs lured sailors into their rocky waters, where they’d be shipwrecked and drown. And Odysseus, desperate to get back to the life and woman for whom he’d fought so valiantly during the Trojan War, instructed his crew under penalty of death to bind him to the mast and not untie him regardless of how much he begged and pleaded.

So when Fagen sings about being out of danger yet finding himself still, somehow, tied to the mast, and when he plaintively muses about the possibility that being held forever just out of reach of the one thing he longs for most might just, indeed, be his destiny – his home, if you will – I remember feeling an emptiness, not to mention a deep and profound sadness over the passing of Walter Becker.

So when Fagen sings about being out of danger yet finding himself still, somehow, tied to the mast, and when he plaintively muses about the possibility that being held forever just out of reach of the one thing he longs for most might just, indeed, be his destiny – his home, if you will – I remember feeling an emptiness, not to mention a deep and profound sadness over the passing of Walter Becker.

And as I read his obit over my coffee, and as that couplet continued echoing up and down the now eerily still chambers of my mind, I kept flashing back to the Walter Becker I saw oh-so-briefly that day in Tower Records. Maybe I was wrong – and Fagen did go on record once saying that Home at Last was about being two New York guys in sunny laid-back L.A. who missed the unique character of the town that made them who they are – but to this day I wonder.

Either way, Walter Becker is gone now and the voice of one of my generation’s most unsung and unlikely musical titans – perhaps the most overlooked, underappreciated and exacting titan of them all – has been stilled.

But rather than me trying to commit to the page any more words about the man, allow me – as was his wont throughout his remarkable and almost defiantly-reclusive career – to let his music speak for him. After all, his remarkable body of musical artistry continues to say so much more than I ever can, or will.

Rest in Peace, Walter. And Godspeed.

Rest in Peace, Walter. And Godspeed.

But as you leave, please do so in the knowledge that there is at least one former clueless, rudderless college kid still out there somewhere; a kid who still listens to four of your albums with the same verve he did so many decades ago, who still retains the ability to occasionally be brought to tears by sheer beauty of your music, and who still hasn’t forgotten a certain IOU that, at least in his mind’s eye, a lifetime ago he scribbled out one day and slipped into your pocket.

And unless I miss my guess, Mr. Becker, you and your guitar are, indeed, home at last.

Second note: My thanks to a few readers who pointed out some factual errors and errors in tone I had made in an earlier version of this essay -- not the least of which was the fact I had (duh) misspelled Donald Fagen's last name. The man is, after all, a contemporary musical genius, not a 19th Century Dickens character.