Even though the world of sports didn’t experience any passings on a level of music’s loss of, say, Aretha Franklin, it did lose a number of greats who left their mark, however faint, upon our collective psyche. Among them:

Tommy McDonald

Tommy McDonald

A throwback to the days when many football stars were built like the rest of us, the 5’9” McDonald – who tipped the scales at (maybe) 175 pounds – was fast enough, tough enough, and elusive enough to earn a spot in both the College and Pro Football Halls of Fame. But he’s noteworthy because of a personal equipment choice he made that was ultimately grandfathered in by the NFL. For that reason, following his retirement after the 1968 season, McDonald would be known, for then and evermore, as the last non-kicker in pro football history to play without a facemask.

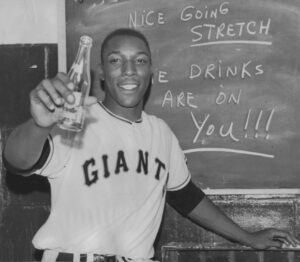

Willie McCovey

The other Willie – Mays – may have been the better player, but he would always (at least in San Francisco’s mind) be something of an outsider to the city; a New York Giant. That’s why, following the move of  Horace Stoneham’s Giants from Coogan’s Bluff to Candlestick Point, big “Stretch” – a Mobile, Alabama boy who'd grown playing with and against his boyhood buddies Hank Aaron and Billy Williams – immediately became his city’s golden boy. And Bay Area sports fans loved that lumbering, uncoiling, uppercut-swinging, giant oak tree of a first baseman like no pro athlete they’d ever loved, before or since. That’s why, to this day, when a left-hand hitter pulls a long home run into the waters beyond the right field wall of the Giants' home park, they don’t hit it into Mays Cove, or Clark Cove, or even Bonds cove. They hit it into McCovey Cove.

Horace Stoneham’s Giants from Coogan’s Bluff to Candlestick Point, big “Stretch” – a Mobile, Alabama boy who'd grown playing with and against his boyhood buddies Hank Aaron and Billy Williams – immediately became his city’s golden boy. And Bay Area sports fans loved that lumbering, uncoiling, uppercut-swinging, giant oak tree of a first baseman like no pro athlete they’d ever loved, before or since. That’s why, to this day, when a left-hand hitter pulls a long home run into the waters beyond the right field wall of the Giants' home park, they don’t hit it into Mays Cove, or Clark Cove, or even Bonds cove. They hit it into McCovey Cove.

Stan Mikita

Stan Mikita

It might be easy to look back and consider the guy the Scottie Pippin to Bobby Hull’s Michael Jordan – a second banana whose brilliance got consistently overshadowed by a legendary teammate whose greatness and star-power turned out to be something for the ages. Except for one thing. To those who really knew, and who played alongside (and against) both Mikita and Hull, the second banana was, in many ways, the better all-round player.

Keith Jackson

Keith Jackson

They say smell is the strongest sense, in that it can transport you back in time via what is termed, “sense memory.” Perhaps, but when millions of Boomers hear, even now, the dulcet sound Jackson’s syrupy but iron-fisted drawl wrapped around one of his trademark phrases – Whoaaaa, Nellie or rumblin’, stumblin’ – they’re transported back in time to the Saturday afternoons of their youth when, in a time before ESPN and wall-to-wall sports, college football was less corporate and less a battle of deep-pocketed superpowers, and more a patchwork quilt of timeless rivalries played out against backdrop after backdrop of brilliant Fall colors, shaking pom-poms, thundering herds, and wide-eyed, proud (and young-once-more) alumni.

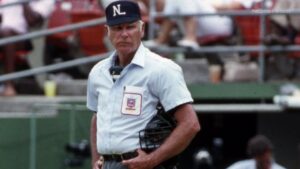

Doug Harvey

Doug Harvey

Precious few ever get to be recognized as the greatest of all time at anything, much less while they’re still doing it. But before he hung up his mask, chest protector and navy blues, Harvey’s ability to call a baseball game – and, particularly, arbitrate its balls and strikes – would be so widely accepted as so profoundly better than anyone in the history of umpiring that he'd gain a nickname that spoke all you needed to know. And that simple, three-letter pet name that baseball insiders once had for the great Doug Harvey and his unimpeachable judgement? “God.”

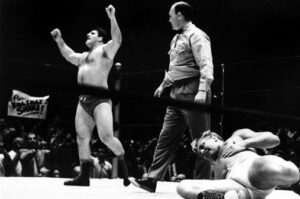

Bruno Sammartino

Bruno Sammartino

In many ways, the single most important professional wrestler of all time. Because once that strong-as-a-bull Italian immigrant, who’d grown up near the coal mines and steel mills of Western Pennsylvania, captured the fancy of New Yorkers, young and old, black and white, male and female, and week after week began packing Madison Square Garden to the rafters for promoter Vince McMahon, Sr., he gave pro wrestling – for the first time in its young life – not just a national superstar. He gave it a national footprint.

Rusty Staub

Rusty Staub

Professional baseball player, restaurateur, author, humanitarian and sportscaster who never seemed to do anything halfway. In 1969, when the young, two-time All Star and Jesuit-trained kid from New Orleans got traded by Houston to the expansion Montreal Expos, he didn’t sulk. Instead, he learned to speak French and vowed to never give a French media interview or try to talk to even one of his French-speaking fans in English – even though his French, at least at that point, was still rough. The French Canadians loved him for his efforts, however, and grew to embrace him as much as any hockey hero they’d ever known. Lovingly nicknamed Le Grande Orange for his barrel chest and shock of red hair, his #10 was the first (and for many years, only) number retired by the Expos. He’d end up becoming the only player in MLB history to get 500 hits for four different teams and one of only two to hit a HR before his 20th birthday and after his 40th. Yet, Rusty Staub would be forever remembered – and loved – in Montreal, if not throughout all of Canada, not for what he did between the lines, but for the character he displayed outside them.

Dwight Clark

Dwight Clark

If the NFL had the equivalent of Bobby Thompson’s “Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” it wouldn’t be Alan Ameche’s one-yard plunge against the Giants in the 1958 NFL title game. It would be Joe Montana’s last-gasp toss in the near corner of the end zone in the final minute of the ‘81 NFC Championship; one slow-footed, mid-round draft pick to another. Because that most unlikely stretch-and-grab by an overachieving wide receiver did more than merely end one dynasty and trigger another. It determined that Clark, a relative unknown who snared what is now referred to as simply “the Catch,” would have his moment of immortality played and replayed for as long as NFL Films continued to create gridiron gods and compose visual gridiron symphonies.

Frank Ramsey

Frank Ramsey

Until Celtic head man Red Auerbach began using Ramsey as his own secret weapon – the first sub off the bench to give his starters an early boost of energy, if not scoring – no one had ever even heard the term that would soon become synonymous with the young man from Kentucky, a term the NBA now uses to honor the one player in the league who best exemplifies the many things Ramsey once did in such a groundbreaking and never-before-seen manner: sixth man

Roger Bannister

Roger Bannister

For much of the 20th Century, breaking a four-minute mile was akin to scaling Mount Everest; not impossible, perhaps, but damn close to it. Yet, just like it took one Brit – Sir Edmund Hillary – to finally scale Everest, it took another – Bannister – to somehow manage to run a mile in less than four minutes. The lean 25-year old medical student walked – or, more to the point, ran – into the record books on a cold and rainy morning in the Spring of 1954 in front of no more than 1,200 or so shivering spectators. Regardless, 3:59:4 minutes later, Roger Bannister had not only broken the tape, he’d sprinted his way into the history books, placing his name alongside those of Babe Ruth, Bobby Jones and Jesse Owens, singular athletes who transcended sport and geographical boundaries to become heroes for the ages. Yet, just months later, like any good stiff-upper-lipper and loyal subject of Her Majesty, at the peak of his fame, the young miler quit running entirely to finish his studies and get on with what would prove to be a long and successful medical career.

Among the other notable sports deaths in 2018:

Among the other notable sports deaths in 2018:

Red Schoendienst, who’d been the oldest living Hall of Famer until passing in June and ceding his title to former Dodger manager, Tommy Lasorda. The little redhead, a line drive-hitting/slick-fielding second baseman, was also winner of five different World Series (as a player with the Braves and player, manager and coach of the Cardinals) – all five of which, oddly enough, came in seven-game series.

Former New York Giant defensive tackle, Dick Modzelewski, and running back Ron Johnson, as well as former Rams’ All-Pro linebacker, Isaiah Robertston.

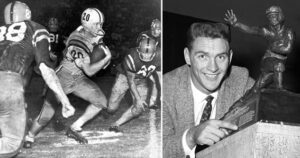

One-time LSU backfield mates, fullback Jimmy Taylor and halfback Billy Cannon, the former of whom went on to become the backbone of Vince Lombardi’s vaunted Green Bay running attack during a ten year run in which that little Cheesehead crossroads earned the moniker “Title Town,” and the latter of whom is still widely regarded as the most beloved athlete in Pelican State history, largely on the basis of his aw-shucks charm, square-jawed good-looks, and now-mythical Halloween night punt return in the final minutes against Ole Miss to clinch not only a 7-3 win for the Tigers, but, by all accounts, the 1959 Heisman Trophy.

One-time LSU backfield mates, fullback Jimmy Taylor and halfback Billy Cannon, the former of whom went on to become the backbone of Vince Lombardi’s vaunted Green Bay running attack during a ten year run in which that little Cheesehead crossroads earned the moniker “Title Town,” and the latter of whom is still widely regarded as the most beloved athlete in Pelican State history, largely on the basis of his aw-shucks charm, square-jawed good-looks, and now-mythical Halloween night punt return in the final minutes against Ole Miss to clinch not only a 7-3 win for the Tigers, but, by all accounts, the 1959 Heisman Trophy.

Women's basketball star Anne Donovan, who put tiny Old Dominion on the map by leading it to back-to-back national championships and then won two Olympic gold medals as well

National League legend, Laurence Henry "Dutch" Rennert, possessor of the single most distinctive strike call in Major League history

British soccer great, Peter Thompson, whose speed, dribbling ability, and electric style of play became the trademark of the great Liverpool teams of the 1960's, teams led by the telegenic bad boy, ladies man, and scoring whiz, George Best

Golfers Hubert Green, who won the 1977 British Open and the 1985 PGA Championship, and who in one seven-year run had six top ten Masters finishes, and Carol Mann, winner of 38 LPGA titles and a woman who, while working the sidelines for ABC and ESPN, became one of the smartest and most respected course reporters in the history of televised golf.

Golfers Hubert Green, who won the 1977 British Open and the 1985 PGA Championship, and who in one seven-year run had six top ten Masters finishes, and Carol Mann, winner of 38 LPGA titles and a woman who, while working the sidelines for ABC and ESPN, became one of the smartest and most respected course reporters in the history of televised golf.

Warren Wells, the speedy Raiders wide receiver who, in the late 60's and early 70's, was on the receiving end of so many of the down-the-field throws launched by Al Davis' legendary "Mad Bomber," Daryle Lamonica

Longtime voice of the New England Patriots, Gil Santos, who started doing games back in 1966 when they were called the Boston Patriots and serving as perennial also-rans in the old AFL

Bennie Cunningham, who, along with Randy Grossman, served as the twin tight ends on Chuck Noll's bone-crushing, Super Bowl-winning Pittsburgh Steeler teams of the 1970's

Earle Bruce, the Ohio State football coach once put in the unenviable position of having to replace a legend; in his case, the immortal Woody Hayes

Earle Bruce, the Ohio State football coach once put in the unenviable position of having to replace a legend; in his case, the immortal Woody Hayes

The architect of the powerful, Stanley Cup-winning New York Islander teams of the 1980's, general manager Bill Torrey

Nikolai Volkoff, who wrestled in the WWF and WWE for decades as the notorious villain, the Iron Sheik

Three-time Wimbledon champion Maria Bueno, who was a quiet force in women's tennis in the late 50's and early 60's

Tex Winter, self-admitted gym rat, ever-doodling X’s and O’s geek, and mad scientist behind the famed “triangle two,” the offense that Phil Jackson rode to a record 11 NBA titles as coach of the Chicago Bulls and Los Angeles Lakers

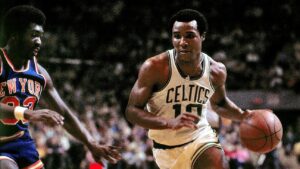

Former Kansas Jayhawk, Celtic bank-shooter, and deadly mid-range marksman, JoJo White – who, at least according to such knowledgeable authorities as Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain, might have been the single greatest shooter of his era

Former Kansas Jayhawk, Celtic bank-shooter, and deadly mid-range marksman, JoJo White – who, at least according to such knowledgeable authorities as Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain, might have been the single greatest shooter of his era

Detroit Lions coach, Darryl Rogers, and Buffalo Bills and L.A. Rams coach, Chuck Knox, the latter of whom had a running game so successful and so ultimately tied to his philosophy that sportswriters soon began calling it, “Ground Chuck”

Billy Connors, journeyman minor leaguer who, through diligence, hard-work and more than a little good fortune, would end up as the pitching coach of the powerful New York Yankee teams that dominated baseball in the late 90’s under Joe Torre

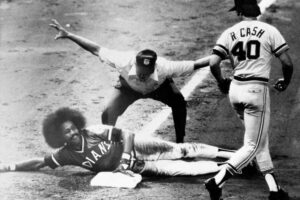

Oscar Gamble, outfielder-turned-designated hitter whose spectacularly outsized afro remains, to this day, much like disco balls and Travolta’s white suit, visual and almost comical shorthand for an era during which natural fibers and traditional looks took a back seat to the wonder of polyester – both the fabric and the attitude

Oscar Gamble, outfielder-turned-designated hitter whose spectacularly outsized afro remains, to this day, much like disco balls and Travolta’s white suit, visual and almost comical shorthand for an era during which natural fibers and traditional looks took a back seat to the wonder of polyester – both the fabric and the attitude

Ed Charles, senior member of the “Miracle Mets” of 1969, a team of fresh-faced kids who, after a largely predictable Game One loss in Baltimore, shocked the baseball world and won four straight games to capture that year's World Series. The first of those came in Game Two when Charles, a part-time third baseman, led off the 9th with a double and eventually came around to score the game winner.

Hal Greer, former Syracuse Nat and Philadelphia 76er, whose curious habit of using his jump shot to shoot his free throws often obscured the fact that he was so dynamic that at the turn of the century he was voted by national sportswriters as one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History

Hal Greer, former Syracuse Nat and Philadelphia 76er, whose curious habit of using his jump shot to shoot his free throws often obscured the fact that he was so dynamic that at the turn of the century he was voted by national sportswriters as one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History

Former Yale football coach, Carmen Cozza, who not only laid the groundwork for future Hall of Famer Calvin Hill’s NFL greatness, but whose New Haven teams became indirectly featured in the funny pages by cartoonist Garry Trudeau of Doonesbury fame, a former Eli, whose hawkish, Vietnam-loving and football-playing character “B.D” was loosely modeled after Cozza’s All-Ivy quarterback, Brian Dowling

Bruce Kison, who, as a young Pirate phenom, won the first World Series game ever played – at the behest of NBC, MLB’s longtime television partner – at night

Bob Beattie, a man as important to the explosion of skiing in the 1960’s as any; first as coach of such Olympic symbols of youthful vitality and swashbuckling charm as Billy Kidd, Jimmie Heuga and Spider Sabich, and then as a raspy voiced color commentator for ABC. In fact, Beattie’s commentary on Franz Klammer’s stunning downhill win in the 1976 Olympics in his native Austria – delivered, he’d later admit, under the influence of a few schnapps to knock back the cold – still ranks as, just maybe, the single finest example of balancing bubbling emotion, real time action, and clinical analysis in the history of televised sports.

Bob Beattie, a man as important to the explosion of skiing in the 1960’s as any; first as coach of such Olympic symbols of youthful vitality and swashbuckling charm as Billy Kidd, Jimmie Heuga and Spider Sabich, and then as a raspy voiced color commentator for ABC. In fact, Beattie’s commentary on Franz Klammer’s stunning downhill win in the 1976 Olympics in his native Austria – delivered, he’d later admit, under the influence of a few schnapps to knock back the cold – still ranks as, just maybe, the single finest example of balancing bubbling emotion, real time action, and clinical analysis in the history of televised sports.