It was, indeed, a bad year for writers – even a few who we never really thought, first and foremost, of as men of letters.

William Goldman

William Goldman

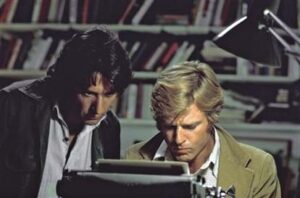

Some contend (reasonably so) the greatest screenwriter in the history of American film was Billy Wilder. Some, likewise, contend it might have been Joseph or Herman Mankiewicz, or Budd Schulberg, or Ben Hecht, or even John Sayles, or Francis Ford Coppola, or the Cohen brothers. But a solid, if not sterling, case could be made that William Goldman, who we lost this Fall – the man behind such gems as the Princess Bride, Marathon Man, and All the President’s Men – was the greatest of them all. Goldman’s scripts offered not just compelling narratives, but some of the wittiest quips (not to mention sharpest dialog) of all time. In fact, his original script for  Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid could serve as am entire master class on one-liners and zingers. And to read that script today, even with no knowledge of the finished film, makes one realize that all director George Roy Hill had to do to was to follow the precise, shot-by-shot instructions Goldman had laid out for him in his stage directions. Yet, to appreciate Bill Goldman’s sheer brilliance as a teller of stories for the big screen, all one has to do is go to a single line of dialogue he pecked out on his Olivetti for All the President’s Men, a simple, five-syllable masterstroke of spoken-word simplicity that distilled the dense web of information Deep Throat was supplying the film's two protagonists into a single, shimmering moment of clarity; a line that has since become, arguably, the most quoted in history, a movie moment that almost overnight became verbal shorthand for virtually every industry in this country, if not every walk of life: “Follow the money.”

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid could serve as am entire master class on one-liners and zingers. And to read that script today, even with no knowledge of the finished film, makes one realize that all director George Roy Hill had to do to was to follow the precise, shot-by-shot instructions Goldman had laid out for him in his stage directions. Yet, to appreciate Bill Goldman’s sheer brilliance as a teller of stories for the big screen, all one has to do is go to a single line of dialogue he pecked out on his Olivetti for All the President’s Men, a simple, five-syllable masterstroke of spoken-word simplicity that distilled the dense web of information Deep Throat was supplying the film's two protagonists into a single, shimmering moment of clarity; a line that has since become, arguably, the most quoted in history, a movie moment that almost overnight became verbal shorthand for virtually every industry in this country, if not every walk of life: “Follow the money.”

Neil Simon

Neil Simon

A guy whose most iconic works – Barefoot in the Park, The Odd Couple, The Goodbye Girl – were not, by any means, his best. Despite his background as young writer for the legendary Your Show of Shows and Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca in the 50’s, and despite at one point in the 60’s, at the peak of his powers, having three first-run hit shows on Broadway at the same time, it wasn’t until over two decades later that he hit his stride and wrote the three stage plays now  considered by critics and insiders to be his finest. Known now as the “Eugene Trilogy” or his “B Plays,” Brighton Beach Memoirs, Biloxi Blues and Broadway Bound – three loving snapshots of his own life as a young Jewish boy, as a soldier/aspiring writer, and, finally, as a budding New York playwright – would prove to be the most honest and funniest works in a canon otherwise overflowing in both honest and funny.

considered by critics and insiders to be his finest. Known now as the “Eugene Trilogy” or his “B Plays,” Brighton Beach Memoirs, Biloxi Blues and Broadway Bound – three loving snapshots of his own life as a young Jewish boy, as a soldier/aspiring writer, and, finally, as a budding New York playwright – would prove to be the most honest and funniest works in a canon otherwise overflowing in both honest and funny.

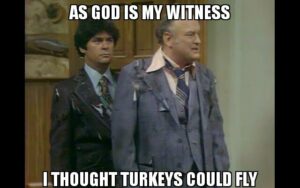

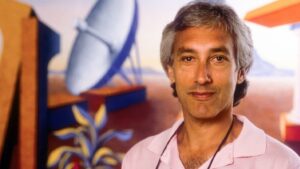

Hugh Wilson

Hugh Wilson

Former journalism student/turned-ad man/turned-TV writer who, following a brief stint at MTM Enterprises, went on to create WKRP in Cincinnati, one of the most intelligent and wonderfully human sitcoms in history. In fact, two of his scripts for WKRP were awarded something called a Humanitas Award, while the show itself – including the classic “Turkey Drop,” a museum-quality sitcom episode about a botched radio promotion that concludes with the now-legendary line,  “As God as my witness, I thought turkeys could fly” – was nominated for two Emmys. And while earning a Humanitas might not mean much to most Americans, Barbara Walters once said of it: “What the Nobel is to literature and the Pulitzer is to journalism, the Humanitas Award has become to American television.”

“As God as my witness, I thought turkeys could fly” – was nominated for two Emmys. And while earning a Humanitas might not mean much to most Americans, Barbara Walters once said of it: “What the Nobel is to literature and the Pulitzer is to journalism, the Humanitas Award has become to American television.”

Mort Walker

Mort Walker

Creator of popular strips Beetle Bailey and its spinoff, Hi and Lois (Lois was Beetle’s big sister) who managed to pull off the near-impossible. He launched a comic strip about a lazy Army private a full year before the Korean War, and one that ran the entire length of Vietnam, that did not feature a  single frame that depicted even a moment of active combat. Not only did Walker have Beetle and his buddies remain in basic training for the entire seven decades he wrote the strip, but he did so without once even mentioning the word “Korea” and made only one passing reference to “Vietnam.” Maybe that explains Beetle’s long-lasting popularity with those of all ages and stripes, even at the height of the Vietnam War and the often violent protests it triggered.

single frame that depicted even a moment of active combat. Not only did Walker have Beetle and his buddies remain in basic training for the entire seven decades he wrote the strip, but he did so without once even mentioning the word “Korea” and made only one passing reference to “Vietnam.” Maybe that explains Beetle’s long-lasting popularity with those of all ages and stripes, even at the height of the Vietnam War and the often violent protests it triggered.

Steven Bochco

Steven Bochco

A television writer whose desire to reflect real life and mirror real people helped change the medium he loved forever. Bochco’s Hill Street Blues in 1981 wasn’t just revolutionary because it introduced the widespread use of machine-gun edits and hand-held cameras. It was revolutionary because his original scripts (and those he edited) told multiple stories about multiple characters, some of which were never fully resolved and some of which ended badly, one way or another. What’s more, some of those arcs spanned  three or four episodes, while others were resolved in under an hour’s time. In fact, it’s not a stretch to say that without the path Hill Street Blues carved through the thicket of predictability and sameness that TV had become by the Reagan Era, subsequent landmark shows like the Sopranos, Mad Men, the West Wing and the Wire might have not been possible, much less conceived. Television, in his day, may have known better writers than Steven Bochco. But – and make no mistake about this – it has never known a more important one.

three or four episodes, while others were resolved in under an hour’s time. In fact, it’s not a stretch to say that without the path Hill Street Blues carved through the thicket of predictability and sameness that TV had become by the Reagan Era, subsequent landmark shows like the Sopranos, Mad Men, the West Wing and the Wire might have not been possible, much less conceived. Television, in his day, may have known better writers than Steven Bochco. But – and make no mistake about this – it has never known a more important one.

Philip Roth

Philip Roth

A prolific, hard-working writer who made a lifetime study of the three things he knew and loved best; sexual desire, 20th Century history, and being a Jew in America. Roth exploded out of the block with a smash, as his 1959 novella, Goodbye, Columbus (a cynical but wonderfully humorous look at driven, upwardly mobile New Jersey Jews and their fascination with social standing), was turned into a hit film starring Richard Benjamin and Ali McGraw. Yet, conspicuous success and money never seemed, ultimately, to drive Roth. To the contrary, he seemed driven by only one thing, his own singular interests as a man at the various stages of life. What's more, much like Neil Young never rested on his laurels as a rock star, and kept pushing himself musically throughout his career, so too Roth never stopped working, never stopped exploring new terrain, or never stopped asking that critical question any great artist must constantly ask himself, “What if…” That’s why, at a time when so many other great 20th Century writers – guys like Mailer, Vonnegut, Capote, Fitzgerald and Faulkner – were either working the talk show circuit or riding the coattails of their once-formidable gifts, Roth was out there after his 60th (and even 70th) birthday, still writing every day, still questioning who we are as a people, and still mining those three fundamental things he seemed to understand as well as any American writer who ever sat down at a blank sheet of paper.

Tom Wolfe

Tom Wolfe

Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood might have opened the floodgates for what was soon being called the "new journalism" – the narrative rendering of compelling non-fiction stories. But it was Wolfe who latched onto that concept and made it more than just another one-off venture. At his peak, his uncanny eye for detail was matched only by his ability to find the poetry in just about any interconnected series of facts. His Electric Kool Aid Acid Test, and (especially) The Right Stuff were as moving as they were journalistically spot-on. As a novelist, Wolfe was a touch less riveting, but hit one true home run – Bonfire of the Vanities, the de facto novel-of-record for the Reagan-fueled, what’s-in-it-for-me 80’s. Yet, if one were to read just one passage to try to understand the brilliance of Tom Wolfe as a man of letters, it might be from a single chapter in his Atlanta-based novel, A Man in Full, one titled “The Saddlebags” – a phrase that young, hotshot equity partners gave to the kind of full-on sweat they were able to generate from an otherwise unsuspecting borrower who sat across the table from them unaware he’d just entered into a deal, not with a group of business partners, but a pack of ravenous wolves.

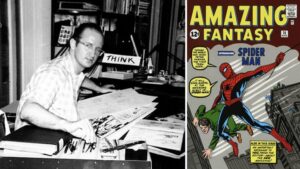

Stan Lee and Steve Ditko

Stan Lee and Steve Ditko

One wrote with words, the other wrote with pictures. As co-creators of Spiderman – arguably, the most human, vulnerable, and beloved comic superhero in publishing history – Lee would often craft general story outlines, hand them off to Ditko, and then watch as they took shape and form, while often traveling into places even he never anticipated. Lee had long been acknowledged as the godfather of the superhero genre, and he received more than his share  of accolades as he took what proved to be an extended victory lap, one on which he soaked up more than his share of praise from the media and his fans. But it was Ditko who proved to be the Zen master of the genre to which Lee gave such a public face. As the New York Times said of him: “Mr. Ditko was noted for his cinematic storytelling, his occasional flights into almost psychedelic abstraction, and the philosophical convictions that often colored his work. Scrupulously private, he had a mystique rare among industry superstars.”

of accolades as he took what proved to be an extended victory lap, one on which he soaked up more than his share of praise from the media and his fans. But it was Ditko who proved to be the Zen master of the genre to which Lee gave such a public face. As the New York Times said of him: “Mr. Ditko was noted for his cinematic storytelling, his occasional flights into almost psychedelic abstraction, and the philosophical convictions that often colored his work. Scrupulously private, he had a mystique rare among industry superstars.”

Ricky Jay

Ricky Jay

He may have been the greatest – and most engaging – up-close, sleight-of-hand magician working today. He was a fringy but essential member of David Mamet’s troupe of actors who seemed to intuit the playwright’s sometimes offbeat rhythms, cadences, and speech patterns, as well as one of director Wes Anderson’s go-to performers and narrators. But, perhaps, more than anything he did on the screen or  in front of a small crowd, Ricky Jay mattered because he spent over 40 years as a engaging writer, chronicling (via a series of fascinating and anecdote-rich books) the wonder of magic, cards, dice and our eternal fixation on the mysterious, the offbeat, and the bizarre.

in front of a small crowd, Ricky Jay mattered because he spent over 40 years as a engaging writer, chronicling (via a series of fascinating and anecdote-rich books) the wonder of magic, cards, dice and our eternal fixation on the mysterious, the offbeat, and the bizarre.

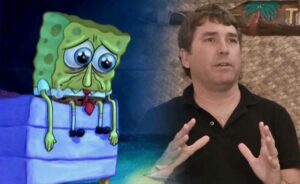

Steve Hillenburg

Former marine biologist whose fascination with animation and love of children stirred him to transform the colorful, illustrated book he’d written on the flora and fauna in a typical tidal basin into a full-blown kids show. Thus was born the biggest animated hit since the Simpsons, the most  widely popular show in the history of Nickelodeon, and a stoner icon as mind-blowing and trance-inducing as anything since the hazy, crazy days of Cheech and Chong, the lords and high-masters of stoner/weed culture. But the by-product of Hillenburg’s little illustrated science book – SpongeBob SquarePants – didn’t just become a hit, it exploded into a force of (ahem) nature, emerging as the most widely distributed franchise in the robust MTV Networks catalog, while spawning not only hundreds of episodes and a full length feature film, but a Broadway musical as well. Not bad for a self-avowed science geek who one day just decided to sit down and try to piece together a simple picture book for early readers about the joys and wonders of seaweed, algae and mollusks.

widely popular show in the history of Nickelodeon, and a stoner icon as mind-blowing and trance-inducing as anything since the hazy, crazy days of Cheech and Chong, the lords and high-masters of stoner/weed culture. But the by-product of Hillenburg’s little illustrated science book – SpongeBob SquarePants – didn’t just become a hit, it exploded into a force of (ahem) nature, emerging as the most widely distributed franchise in the robust MTV Networks catalog, while spawning not only hundreds of episodes and a full length feature film, but a Broadway musical as well. Not bad for a self-avowed science geek who one day just decided to sit down and try to piece together a simple picture book for early readers about the joys and wonders of seaweed, algae and mollusks.

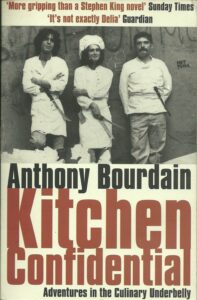

Anthony Bourdain

Anthony Bourdain

In this Trumpian age of ours – an age during which, for countless Americans, unless something happens on TV, it doesn’t really happen at all – it’s easy to forget that before Anthony Bourdain became a mega-star of the small screen, he was little more than a troubled recovering rock-n-roller from New York hounded by personal demons and a guy who found himself saved by the simple fact he had a unique talent for cooking, if not love of food. Because as compelling as Bourdain may have been on TV, he was even more so on the written page. His first article for the New Yorker,  “Don’t Eat Before Reading This,” brought his bold and daring culinary worldview to the attention of the New York publishing community. And it was that one frank, no-holds-barred account of life in a professional kitchen that led to his breakthrough 2000 memoir, Kitchen Confidential, which overnight became a New York Times best seller and established him as the most soulful, honest and irreverent voice in a landscape suddenly overrun with TV foodies – men and women from all stations of life and degrees of privilege who continued to have to work overtime to do half the things that that aging ex-rocker seemed to be able to do by just punching the clock.

“Don’t Eat Before Reading This,” brought his bold and daring culinary worldview to the attention of the New York publishing community. And it was that one frank, no-holds-barred account of life in a professional kitchen that led to his breakthrough 2000 memoir, Kitchen Confidential, which overnight became a New York Times best seller and established him as the most soulful, honest and irreverent voice in a landscape suddenly overrun with TV foodies – men and women from all stations of life and degrees of privilege who continued to have to work overtime to do half the things that that aging ex-rocker seemed to be able to do by just punching the clock.

Music deaths in 2018

Actor deaths in 2018

Business deaths in 2018

Sports deaths in 2018

Miscellaneous deaths in 2018