Besides Aretha Franklin, a giant for the ages and a singer for all time, the music world also lost a number of lesser lights this year who, nevertheless, left their mark on our collective soul. Among them:

Besides Aretha Franklin, a giant for the ages and a singer for all time, the music world also lost a number of lesser lights this year who, nevertheless, left their mark on our collective soul. Among them:

Danny Kirwan

He may have spent much of his life a homeless and helpless substance abuser, but prior to being cast adrift by his demons, he brought a deep and abiding love of melody, if not a pop sensibility to Fleetwood Mac – which had been limping along as  an earnest but only marginally successful blues band. Kirwan’s influence compelled even the band’s leader, Peter Green, a longtime blues hard-liner, to travel down an entirely new musical sideroad. Green, in fact, would later admit he never could have written his band’s breakthrough single, Albatross, without all that Kirwan had taught him. One other Fleetwood Mac pop artifact that, likely, never would have achieved half of what it did without the ill-fated Kirwan, his hypnotic melodies, and his ever-so-gentle feel for his instrument: the band’s pre-Buckingham/Nicks gem, Bare Trees, a musical delight of the highest order on which his touch (and tremolo-tinged riffs) will be heard for as long as people long for and listen to painfully beautiful pop tunes.

an earnest but only marginally successful blues band. Kirwan’s influence compelled even the band’s leader, Peter Green, a longtime blues hard-liner, to travel down an entirely new musical sideroad. Green, in fact, would later admit he never could have written his band’s breakthrough single, Albatross, without all that Kirwan had taught him. One other Fleetwood Mac pop artifact that, likely, never would have achieved half of what it did without the ill-fated Kirwan, his hypnotic melodies, and his ever-so-gentle feel for his instrument: the band’s pre-Buckingham/Nicks gem, Bare Trees, a musical delight of the highest order on which his touch (and tremolo-tinged riffs) will be heard for as long as people long for and listen to painfully beautiful pop tunes.

Joe Osborn

Joe Osborn

In the 60’s and 70’s, he was among the most prolific and successful bass players in the glory days of Top 40 pop, before moving to Nashville and becoming the very same thing in 80’s country. Osborn was so prolific and in-demand, in fact, that it was entirely possible that no Top 40 radio station in those first two decades, nor any country station at any point in the last, spent even a single hour in which it didn’t play at least one or two records that featured the former Louisiana boy’s alternately intoxicating and driving (yet always self-taught) bass lines.

Bob Dorough

Bob Dorough

Had he only played with jazz titans Blossom Dearie and Miles Davis, and only influenced the great Mose Allison to the extent that he did, he might have earned a spot here. But in 1973, Madison Ave ad man extraordinaire Dave McCall approached Dorough, a respected but mostly unknown New York jazz pianist, and asked him to set the multiplication tables to music for his client, ABC. The result was an innocent yet eerily evocative little ditty titled Three is a Magic Number, the first in a series of Dorough compositions that would be packaged on Saturday mornings by the network as Multiplication Rock. The concept would expand, of course, yet Dorough would remain central to it, singing and playing on every song in the series. And now, looking back, if get-rich-quick real estate videos and extended Thigh-Master and Flowbee ads represent the Dark Ages of interstitial TV content, Schoolhouse Rock has to remain, now and forevermore, its Renaissance.

Nancy Wilson

Nancy Wilson

Even though her music could trace its roots back to Bessie Smith, Ethyl Waters and the jazz and blues of the 30’s and 40’s, her career took root in the 50’s, a decade during which it was almost impossible to swing a dead cat and not hit a dozen or so innovative and daring female song stylists. Yet, unlike many contemporaries, Wilson refused to be pigeonholed, either as an artist or a woman. She, in fact, constantly went her own way. That’s why to listen today to her oddly, and almost defiantly different 1964 single (You Don’t Know) How Glad I Am, and to understand it was released and became a hit at the very peak of Beatlemania, is to understand that the only voice to which she ever truly listed was the one in her soul. That’s probably why, even as a young woman, Nancy Wilson – singer, actress, music historian, civil rights activist, wife, mother and woman of indomitable class – often seemed the only adult in the room.

Roy Clark

Roy Clark

To millions, he was little more than one half of the lame, joke-spewing hayseed co-hosts of the syndicated, pickin’-and-grinnin’ giant, Hee Haw. But to others, he was one of the most wildly talented players to ever come down the pike. Having cut his teeth as, literally, a boy doing club gigs in and around Washington, DC, he’d soon win the National Banjo Championship as both a 15 and 16 year old, become a teenage member of rockabilly legend Wanda Jackson’s band, as well as Jimmy Dean’s, appear on the Tonight Show two years even before Johnny Carson would take over, tour with both Red Foley and Ernest Tubb, earn a spot on Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts, become a semi-regular on the Beverly Hillbillies, guest star on the Odd Couple, become a member of the Grand Ole’ Opry, and be inducted into Country Music Hall of Fame – all while still a young man. Not bad for a guy who once said he never intended to become a country guitar player. He just wanted to play – and pick – whatever made him happy.

Marty Balin

Marty Balin

Yes, by the 1970’s the Jefferson Airplane, the darlings of the 60’s counter culture, had regrettably reinvented themselves as Jefferson Starship, a truly awful band of unapologetic and nearly untethered rock and roll mercenaries. And Balin, who’d left for a few years in the late 60’s, returned as the poster child of all that bad art and good commerce. (I had a taste of the real world, when I went down on you...Really?) Regardless, as lead singer of the original Airplane, Balin penned and sang two magnificent songs that some Boomers, even now, will take to their graves. Today, a simple but exquisitely produced ballad from the Airplane's breakthrough album, Surrealistic Pillow, was no doubt playing on many a turntable when at least a few of those kids experienced (ahem) physical communion for the first time. Meanwhile, Volunteers is one of the few anti-establishment songs from the era that, while it may no longer communicate even half the rage and defiance so many Boomers once felt, still manages to somehow hold up after all these years.

Dennis Edwards

Dennis Edwards

Under Smokey Robinson, the Temptations were David Ruffin’s group and rode his syrupy yet gently raspy tenor to such lofty heights as My Girl and The Way You Do the Things You Do. But after one particular 45, Get Ready, failed to make a dent on the Top 20, Berry Gordy axed Robinson as the group’s producer and replaced him with a talented young wunderkind named Norman Whitfield. In no time, the Temps had stopped singing about love and romance and went about attempting to set the most searing issues in Black America to music. To serve as the voice of those real-life issues, Whitfield hand-picked a singer whose raw and occasionally angry instrument captured perfectly the Temps’ new-found sense of social purpose. And when that happened, almost overnight, Just My Imagination and Since I Lost My Baby exploded into Cloud Nine, Ball of Confusion, Runaway Child, Running Wild and, above all, Papa Was a Rolling Stone.

Tony Joe White

Tony Joe White

A Cajun singer, songwriter and picker whose muscular talent – every now and then, anyway – was able to rise above his almost pathological laid-back attitude and militant aversion to traveling too far from his beloved home in the little Louisiana crossroads town of Goodwill. To many, Polk Salad Annie was just a gimmick song. But to others, it was a magical two and a half minutes worth of authentic bayou patois, storytelling and swamp guitar; two and a half minutes of rich, down-home attitude that exposed more truth than a whole season's worth of reality shows or Anne Rice novels. But even if Tony Joe White did nothing else in his time among us than write Rainy Night in Georgia – a stunningly lyrical ballad that, on his very first listen of Brook Benton's rendering, he didn’t even recognize as his own – he would have earned more than a simple passing mention on this page.

Rick Hall

Until he had a falling out with Aretha Franklin’s then-husband, who promised never to record in his studio again, Hall’s revered FAME Studio in tiny Muscle Shoals, Alabama served as the unlikely birthplace of a brand of soul and R&B that was, and is still to this day, a high water mark in American pop culture; everything from Aretha’s Do Right Woman (Do Right Man) and Wilson Pickett’s Hey, Jude to Clarence Carter’s Slip Away, James and Bobby Purify’s I’m Your Puppet, Etta James’ Tell Mama, Bob Seger’s Old Time Rock and Roll, and the Rolling Stones’ Wild Horses.

Ray Thomas

Ray Thomas

While he wrote and sang many of the Moody Blues’ most beloved and iconic album cuts – such evocative progressive rock ballads as Dear Diary, Tuesday Afternoon and Are You Sitting Comfortably? – for millions of Boomers, Thomas’ flute solo on Justin Heyward’s ethereal Knights in White Satin will remain, at least for as long as they’re able to smoke a little weed and sport a set of headphones, prog-rock’s defining moment.

Ed King

Ed King

He may have cut his teeth with the Strawberry Alarm Clock and it may have been him playing that fuzzy solo on the poppy little psychedelic gem, Incense and Peppermints. But where King left a little piece of himself all over our cement-fresh psyches would take place a decade later in a different part of the country, and on an entirely different kind of record. Because even though his next band would notably feature three lead guitar players, and even though all three of those players would soon become famous, it not infamous, for blistering live solos of interminable length, it was only one of those guitarists – Ed King – who (following a drawled countdown by lead singer Ronnie Van Zant) who’d pluck out the first few notes of what would become one of the true anthems of rock, Lynyrd Skynyrd's Sweet Home Alabama.

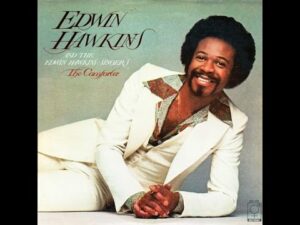

Edwin Hawkins

Edwin Hawkins

He never thought of himself as a pop star; he was, after all, just a choir director at a small Southern Baptist church in Oakland. Yet two moments that he and his choir once committed to vinyl became touchstones for his generation. On Melanie’s Lay Down (Candles in the Rain), the Edwin Hawkins Singers’ took what was ostensibly a reflection of the folk singer’s largely forgettable performance at Woodstock and transformed it into a protest anthem of stunning spiritual power and majesty. And Oh Happy Day, the choir director’s mash-up arrangement of long lost 18th Century hymn and 18th Century melody – recorded by his own choir at his own church in the heart of the ghetto in his own hometown – which topped the charts in 1969, stands to this day a touchstone of an era when Americans so sought salvation from the chaos about them that a single uplifting gospel 45 managed to outsell even the Beatles.

Among the other notable musical passings of 2018:

Joe Jackson

Joe Jackson

Domineering patriarch of the musical Jacksons who rode his son’s outsized talent to gain an outsized level of sway in the industry that, at the end of the day, had little use for him

Matt Murphy

Talented Blues Brothers guitarist who appeared as a short-order cook and Aretha Franklin’s husband in the Jake and Elwood movie of the same name

D.J. Fontana

Elvis Presley’s drummer during his early and historic days at Sun Records and on the Louisiana Hayride

Gary Burden

Gary Burden

Prolific graphic artist responsible for the design of hundreds of classic album covers, including Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s Déjà Vu, Joni Mitchell’s Blue, the Eagles’ Desperado, Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush and the Doors’ Morrison Hotel and Hard Rock Café

Hazel Smith

Nashville publicist, goodwill ambassador, and spiritual godmother who, while working on behalf of one of her clients, Tompall and the Glaser Brothers, first uttered the phrase, “Outlaw Country,” thereby branding a type of country that would, at least for a time, eclipse the very music from which it sprang

Vic Damone

Italian crooner and 50’s hit-maker who – some say out of deference to his dear friend, Frank Sinatra, and some say because mobsters once held upside down out a hotel window by his ankles – turned down the role of Johnny Fontaine in the Godfather

Hugh Masekela

Barrier-shattering South African trumpeter whose music was described by Eric Burdon in the song Monterey as “black as night” and whose brazen horn was featured on the Byrds’ wonderful So You Wanna Be a Rock and Roll Star

Dolores O’Riordan

Dolores O’Riordan

Sultry voiced siren and lead singer of the Cranberries

Roy Hargrove

Groundbreaking trumpeter who bridged the often opposing worlds of hip-hop and classic jazz

Jim Rodford

Founding member of Argent and third bassist for the Kinks who played with Ray Davies’ band from the late 70’s until they disbanded in 1996

Charles Neville

Charles Neville

Saxophone playing member of New Orleans’ favorite sons, the Neville Brothers

Randy Scruggs

Earl’s boy, who was a pretty fair picker in his own right

Yvonne Staples

Pop Staples’ oldest girl, who not only doubled as the Staples Singers’ manager, but who can be heard singing background on such stirring gospel-pop gems as Respect Yourself and I’ll Take You There

Business Deaths of 2018

Sports Deaths of 2018

Actor Deaths of 2018

Miscellaneous Deaths of 2018