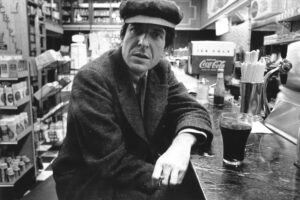

Within hours of each other this week, my generation lost two of its greatest songwriters. Leonard Cohen was a brilliant and iconoclastic Canadian poet who went through life thinly disguised as a troubadour/folk singer. Leon Russell, meanwhile, was a one-time piano-playing prodigy from a red-dirt town in Oklahoma who over a half century ago moved to L.A. and reinvented himself as a boogie-woogie, rock 'n roll shaman that, at times, seemed dropped from another planet.

Within hours of each other this week, my generation lost two of its greatest songwriters. Leonard Cohen was a brilliant and iconoclastic Canadian poet who went through life thinly disguised as a troubadour/folk singer. Leon Russell, meanwhile, was a one-time piano-playing prodigy from a red-dirt town in Oklahoma who over a half century ago moved to L.A. and reinvented himself as a boogie-woogie, rock 'n roll shaman that, at times, seemed dropped from another planet.

Yet for all their greatness and mutual commitment to the exacting discipline of crafting distinctive pop tunes, each writer had one -- and I mean one -- crystalline moment during which the tumblers fell into place, the doors to heaven cracked ajar, and they found it within themselves to marry words and melody perfectly and create a song that is now rightly considered called a masterpiece.

In Cohen's case, his moment of divinity came with his 1984 release, Hallelujah, which a decade later the ill-fated singer Jeff Buckley covered on his album, Grace. Buckley's spine-tingling take remained largely undiscovered for the balance of the decade until the eve of the millennium or so, at which point film and television musical directors, one by one, began stumbling upon it and using it as Hollywood shorthand for a moment in which an onscreen character achieves a spiritual awakening.

In short order, the song was everywhere on the pop scene, particularly on network TV where it added an element of texture and poignancy to an ungodly parade of shows over two decades: NCIS, The West Wing, Crossing Jordan, ER, Ugly Betty, Criminal Minds, The O.C., House, Third Watch and Without a Trace. And that is literally just a handful of hour-long dramas that Buckley's version of the song, no pun intended, graced during that period.

Yet despite that hyper-exposure, Jeff Buckley's Hallelujah remains transcendent. That is truly the best word I can conjure up. If you don't believe me, close your eyes and listen for yourself.

Jeff Buckley singing Leonard Cohen's Hallelujah

Russell's masterpiece never came close to Hallelujah's almost celestial level of pop acclaim and exposure, it was no less soulful or influential, especially to those in his own industry. A raw and honest ballad written for his debut solo album, A Song for You was never released as a single. What's more, the eponymous album that spawned it -- released early in 1970 -- went virtually nowhere when it hit the stores. As a result, A Song for You might have sunk quietly and remained buried in the pop culture graveyard, and that would have been it.

But just one year later, Russell's remarkable little song was discovered, recorded and released as a 45 by, of all people, Andy Williams. Williams' version of A Song for You gave further proof to its true greatness and earned the singer a spot on the adult charts. Then, two years after that, the sadly forgotten Donny Hathaway likewise did a cover, which elbowed its way into the Top 40 -- this time on the soul charts. Willie Nelson, meanwhile, then a virtual unknown, did the same and earned for himself one of his very first hits as a performer -- this time on the country charts.

In time, A Song for You found itself being recorded with greater and greater frequency by singers across the board. Soon the song became a rite of passage for vocalists of all shades and stripes -- not unlike the joke "The Aristocrats" was for stand-up comedians; a rich and far-from-blank canvas to be examined, explored, interpreted and ultimately marked with each artist's own signature.

To date, A Song for You (like Russell's Superstar, another insider's ballad) has been licensed to hundreds upon hundreds of singers the world over, ranging from Neil Diamond, Jaye P. Morgan and the Carpenters to Herbie Hancock, Simply Red and Bizzy Bone.

But just as Buckley transformed Hallelujah, one version of A Song for You stands above them all. And no one, and I mean no one, put his stamp on A Song for You quite like the great Ray Charles. I promise you, give me a year, or ten, I'm not sure I could come up with a more perfect union of song and singer, or a more perfect marriage of message and messenger. Again, if you've somehow managed to not hear this classic Ray Charles recording over the years, listen and experience its timeless and poignant beauty for yourself.

Ray Charles singing Leon Russell's A Song for You

While, as compositions, both Hallelujah and A Song for You are musical forces of nature, and both achieve a level of greatness reserved for precious few pop song, neither were the tunes I chose to play when I heard that the men who'd written them had passed. Nope. I selected a couple of lesser known songs that had more meaning to me personally, had seared themselves deeper into my consciousness, and had connected me to their composers in a way that trumped anything else the two men ever wrote.

In the case of Cohen, it was a song I'd discovered one lonely night, when restless and unable to sleep, I got out of bed, went to the computer, and there, alone with my thoughts, fears and uncertainties, went to YouTube and began scurrying down one rabbit hole after another. And it was down one such hole that I came upon a song I vaguely remembered from my past. Sisters of Mercy first saw the light of day in Robert Altman's anti-western McCabe and Mrs. Miller, which I'd seen years ago when it first came out.

In the case of Cohen, it was a song I'd discovered one lonely night, when restless and unable to sleep, I got out of bed, went to the computer, and there, alone with my thoughts, fears and uncertainties, went to YouTube and began scurrying down one rabbit hole after another. And it was down one such hole that I came upon a song I vaguely remembered from my past. Sisters of Mercy first saw the light of day in Robert Altman's anti-western McCabe and Mrs. Miller, which I'd seen years ago when it first came out.

What I stumbled upon that night was a slightly eerie song that, like Altman's daring and highly unconventional film, was about a makeshift brothel in a time long-ago, about the ladies who called it home, and about the comforts, physical or otherwise, they tenderly dispatched to lonely men with dwindling options. And the more I listened, and the more Cohen's words and imagery crawled inside me, the more I realized I may have just stumbled upon the most spiritual pop tune ever written -- Hallelujah included.

In fact, I'm not sure I've heard Sisters of Mercy since and not felt myself swallowing hard to choke back the waves of unleashed emotions.

Because while, on the surface, Sisters of Mercy is about ladies who ply the proverbial world's oldest trade, what it's really about is so much more. With its haunting religious imagery invoking devout nuns and their odd and selfless marriages to an unseen god, Cohen's song becomes a paean to spiritual comfort-givers on the darkest and loneliest of nights. Yes, Sisters of Mercy is about hard women who happen to trade sex for dollars, but it is also about weary travelers and about the compassionate souls who hear their confessions and forgive them their sins.

Cohen's is a song, above all, about communion; momentary, transitory, but sweet life-affirming communion. And that night, his words, images and melody helped me forget, if only for a moment, all those reasons why I couldn't bring myself to sleep.

In fact, I believe that's why I remain so moved by Beth Orton's rendering, which she recorded live at a tribute concert. Because in her hands, Sisters of Mercy removes any and all traces of sex and elevates the loneliness, empathy and fleeting moments of fragile and often indelicate human intimacy to a place just this side of godliness. And it celebrates those tiny shards of connection that are as much emotional and spiritual as they are physical.

Beth Orton singing Leonard Cohen's Sisters of Mercy

In the case of Russell, the song I chose was virtually the opposite, at least in terms of tone. Though both are ultimately songs of celebration, Sisters of Mercy's is somber, reverential and even a little sadly resigned. Russell's Rainbow in Your Eyes, on the other hand, is joyous, and alive and brimming with light.

Written and recorded following his very first marriage after 35 years' worth of life as a single musician and one night stands, the song starts out innocent and slightly angelic before Russell's blistering organ abruptly rips open its choir robe to reveal something joyful and devilish about the union of two gypsy hearts who, at least for a moment, found each other.

Rainbow in Your Eyes will never be counted among Leon Russell's greatest love songs, but that's not for lack of merit. To the contrary, it's a vibrant, soaring and rapturous hosanna to love's transformative power.

If anything, it never got its due for one simple reason; an almost criminal lack of exposure. Since his marriage (to backup singer Mary McCready) ended up lasting less time than it probably took to produce the album, and its demise was apparently painful to the legendary sideman and songwriter, Russell did little to promote the Wedding Album upon its initial pressing. What's more, he subsequently kept it from being released on CD for nearly 30 years. As a result, very few ever heard it or got a chance to set the needle down on Side A and experience its remarkable gateway song.

Let me do my small part in trying to correct that situation right now and play for you a recording that takes me back to, of all places, a basketball court at the Montgomery, Alabama YMCA, and back to a simpler time for me, when life, like Russell's joyous and joyful song, was defined less by choices made and roads taken than by beauty, light, and the almost limitless options that lay ahead.

And as I write this now, I realize those two songs I played had more than a few things in common, and maybe that's why I chose them. They're both celebrations. They're both, in their own way, love songs. But more than anything, they're two songs that share a common lyrical image -- that of two hearts beating closely and with one another, in one case for a lifetime, and in the other a few precious moments.

Rest in peace, Mr. Cohen. And thank you. Thank you for Suzanne. Thank you for I'm Your Man, Bird on a Wire, Who on Fire, Hallelujah, Sisters of Mercy, and the rest. And thank you too for your ceaseless dedication to your craft, and for serving as both a poet and a moral bellwether for us. We will likely never see your kind again.

And Mr. Russell. I wish you eternal peace, and thank you too. Thank you for making me chuckle. Making me think. And, most of all, making me feel.

And, finally, as a musician who once lent your gifts to Pet Sounds, who, unlike almost every other studio musician the guy ever hired, had the balls to never take Phil Spector's idiosyncratic crap, who played anonymously on hundreds of hits, big and small, by artists ranging from Gary Lewis and Glen Campbell to Eric Clapton and J.J. Cale, who recorded in Nashville with the legendary Owen Bradley, who pieced together and served as the backbone of Joe Cocker's Mad Dogs and Englishmen band, and who was key part of George Harrison's Concert for Bangladesh, to name but a few, thank you for leaving your fingerprints all over something I once took for granted, but something that now I've come to fully appreciate; the rich, textured and unforgettable soundtrack of my life.

Here's to heartbeats, gentlemen, and to those who continue to seek, feel and, above all, find comfort in them. From all of us to both of you, thanks again.

And Godspeed.