As I continued piecing together the stories behind this list of 40 people who died this past year, whose lives and impact were under-appreciated or mis-represented by many in the media, one thing became clear. The deeper into the list I got, the harder it became to distill the legacies into two hundred or so words. So forgive the fact that these are slightly longer than prior entries. Also, since they did grow in length I also chose to break up the final ten names into two lists of five. Because to capture what these folks meant to America and/or American pop culture turned out to be exercise that utterly defied brevity.

As I continued piecing together the stories behind this list of 40 people who died this past year, whose lives and impact were under-appreciated or mis-represented by many in the media, one thing became clear. The deeper into the list I got, the harder it became to distill the legacies into two hundred or so words. So forgive the fact that these are slightly longer than prior entries. Also, since they did grow in length I also chose to break up the final ten names into two lists of five. Because to capture what these folks meant to America and/or American pop culture turned out to be exercise that utterly defied brevity.

Please watch for the second half of Part IV tomorrow. And as always, your comments, shares and likes are appreciated.

10. Dave Brubeck

10. Dave Brubeck

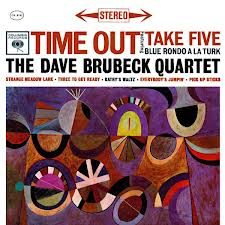

If you were to assemble of Mount Rushmore of Jazz – the four titans whose contributions forever changed the only 100% indigenous art form ever developed in this country, and who most greatly influenced all who would follow in their footsteps – you might argue for some combination of the usual suspects; giants like Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and John Coltrane. But a handful of old-school purists might also argue for the inclusion of Brubeck, one of the most daring, risk-taking and envelope-pushing composers the world of jazz has ever known. Because no man in history experimented any more with polytonality and time-signature – that is, the amount of beats played in any given measure of music – than him. And no one challenged listeners on a more consistent basis, or dared them more often to take nothing for granted. Which is ironic, because the album that became most closely identified with Dave Brubeck, a record which became the first jazz release in history to sell a million copies, and a record which would in time come to be regarded as one of the ten jazz albums in history – 1959's Time Out – was a study in time signature experimentation from beginning to end. And by all rights, the album shouldn’t have sold a lick, much less become a crossover sensation. Even the disc's biggest hit, Take Five, a delicious exercise in 50s cool which became the largest selling jazz single of all time, was recorded in 5/4 -- a time signature that under normal circumstances might otherwise doom a single to the commercial gallows, by way of the cut-out bin.

A remarkably strong-willed yet self-effacing man, Brubeck spent his entire life as a guy always willing to take a back seat so that others might have the spotlight. When in 1954, he became only the second jazz artist to grace the cover of Time, he was embarrassed, believing that Ellington deserved the honor more, and that the only reason he wasn’t was on the cover instead of Brubeck was because the Duke was black. So when a smiling Ellington knocked on his door one night to show him the issue, which had just rolled off the presses, all Brubeck could sheepishly say was, “You deserved it more.” Then five years later, when saxophonist Paul Desmond brought in two separate and ill-defined musical themes he’d been developing, and played them for Brubeck, the pianist got wildly excited at what Desmond showed him. So he asked the sax player if he could take them home that night to work on them. When he returned to the studio the following morning, what he had was the sheet music for a single song he decided to call, almost as an afterthought, Take Five. Yet when the album on which Take Five appeared was released, and the 45 of the song sent to radio stations across the country, the only name that appeared below the title was Desmond’s. And the only guy who for all those years received all those millions in songwriting royalties was the guy who, according to Brubeck, deserved them – since he, and only he, had written Take Five.

A remarkably strong-willed yet self-effacing man, Brubeck spent his entire life as a guy always willing to take a back seat so that others might have the spotlight. When in 1954, he became only the second jazz artist to grace the cover of Time, he was embarrassed, believing that Ellington deserved the honor more, and that the only reason he wasn’t was on the cover instead of Brubeck was because the Duke was black. So when a smiling Ellington knocked on his door one night to show him the issue, which had just rolled off the presses, all Brubeck could sheepishly say was, “You deserved it more.” Then five years later, when saxophonist Paul Desmond brought in two separate and ill-defined musical themes he’d been developing, and played them for Brubeck, the pianist got wildly excited at what Desmond showed him. So he asked the sax player if he could take them home that night to work on them. When he returned to the studio the following morning, what he had was the sheet music for a single song he decided to call, almost as an afterthought, Take Five. Yet when the album on which Take Five appeared was released, and the 45 of the song sent to radio stations across the country, the only name that appeared below the title was Desmond’s. And the only guy who for all those years received all those millions in songwriting royalties was the guy who, according to Brubeck, deserved them – since he, and only he, had written Take Five.

The 60s are still thought of as artistically daring and wildly experimental, while the 50s are regarded by many as an almost vapid era defined by Ike, suburban sprawl, and such oddities as drive-ins, hula hoops and Davy Crockett hats. But when you look at groundbreaking artistic styles like Jack Kerouac’s, J.D. Salinger’s and Allen Ginsberg’s stream-of- consciousness writing, Jackson Pollock’s dripping and pouring, Marlon Brando’s and Elia Kazan’s uber-realistic acting and directing – along with, of course, Brubeck’s endless experimenting with tone, form, style and time, you realize that, in many ways, artists in the 50s took far more chances and broke way more rules than those in the decade that followed. And in many ways – even more than, say, Elvis Presley, tail fins, James Dean and hoop skirts – if there is one artifact of 50s-era culture that utterly captures the essence of that decade’s vibe, look and attitude it is Dave Brubeck’s Time Out – from its wild collection of songs and influences, to its ultra-hip, cocktail-cool and wonderfully era-defining cover. As the New York Times wrote of him following his death a few months back, “He did not always please the critics, who often described his music as schematic, bombastic and – a word he particularly disliked – stolid. But his very stubbornness and strangeness – the blockiness of his playing, the oppositional push-and-pull between his piano and Paul Desmond’s alto saxophone – make the Brubeck quartet’s best work still sound original.”

consciousness writing, Jackson Pollock’s dripping and pouring, Marlon Brando’s and Elia Kazan’s uber-realistic acting and directing – along with, of course, Brubeck’s endless experimenting with tone, form, style and time, you realize that, in many ways, artists in the 50s took far more chances and broke way more rules than those in the decade that followed. And in many ways – even more than, say, Elvis Presley, tail fins, James Dean and hoop skirts – if there is one artifact of 50s-era culture that utterly captures the essence of that decade’s vibe, look and attitude it is Dave Brubeck’s Time Out – from its wild collection of songs and influences, to its ultra-hip, cocktail-cool and wonderfully era-defining cover. As the New York Times wrote of him following his death a few months back, “He did not always please the critics, who often described his music as schematic, bombastic and – a word he particularly disliked – stolid. But his very stubbornness and strangeness – the blockiness of his playing, the oppositional push-and-pull between his piano and Paul Desmond’s alto saxophone – make the Brubeck quartet’s best work still sound original.”

Sure, Dave Brubeck died in 2012. Most people know that. I'm just not sure most people know what a cultural and artistic giant he was, or just how highly our children's children will someday regard him.

9. Donald “Duck” Dunn

I never knew or met Dunn, but my sense is he’d hate the fact I’m sitting here writing this. He’d despise, in other words, being singled out or being placed in anyone’s spotlight, however small. Because Dunn was a bass  player’s bass player, and he played the instrument as he apparently viewed it; as background; as foundation; as one of the three building blocks of any great R&B tune – the others being the drums and, in the case of Dunn anyway, the guitar. Because Duck Dunn comprised one third of one of the most storied and stunning forces of nature in the long and glorious history of rock ‘n roll, the powerful, driving rhythm section that in the 1960s called Stax Records in Memphis home – a trio of backbeat players which included Dunn, Al Jackson, Jr. on drums and Steve Cropper on guitar. Together, those three lords of the groove established one infectious rhythm after another, to the point that it probably only seems that all a legend like Isaac

player’s bass player, and he played the instrument as he apparently viewed it; as background; as foundation; as one of the three building blocks of any great R&B tune – the others being the drums and, in the case of Dunn anyway, the guitar. Because Duck Dunn comprised one third of one of the most storied and stunning forces of nature in the long and glorious history of rock ‘n roll, the powerful, driving rhythm section that in the 1960s called Stax Records in Memphis home – a trio of backbeat players which included Dunn, Al Jackson, Jr. on drums and Steve Cropper on guitar. Together, those three lords of the groove established one infectious rhythm after another, to the point that it probably only seems that all a legend like Isaac  Hayes, Eddie Floyd, Otis Redding, Carla Thomas, Wilson Pickett, Save and Dave, Aretha Franklin or the Staples Singers had to do was simply step to the mic, strap it down, and hold on tight. I’m not trying to make light of these people’s talents or minimize their contributions. They were all brilliant vocalists, and all worthy of singing lead in God’s house band. I’m just trying to point out just how vital Dunn, Jackson and Cropper were to not only Memphis Soul, but the history of American music.

Hayes, Eddie Floyd, Otis Redding, Carla Thomas, Wilson Pickett, Save and Dave, Aretha Franklin or the Staples Singers had to do was simply step to the mic, strap it down, and hold on tight. I’m not trying to make light of these people’s talents or minimize their contributions. They were all brilliant vocalists, and all worthy of singing lead in God’s house band. I’m just trying to point out just how vital Dunn, Jackson and Cropper were to not only Memphis Soul, but the history of American music.

Some may remember the humble, soft-spoken Dunn as the pipe-smoking bassist of the Blues Brothers Band, who not only played with them on Saturday Night Live, but was a featured in the two movies. Others may be under the mistaken impression he was the guy playing the funky, bluesy bass on Booker T. and the MG’s first hit, Green Onions. (He wasn’t. He joined the band a year after the song was released.) But who Duck Dunn was, was one of the most anonymous great musicians of his or any other time, and an entirely self-taught bassist whose brilliance was measured not so much by the notes he played but by the company he kept. (When you get a chance, search the phrase “Duck Dunn discography,” and then sit back and prepare to be amazed.)

Some may remember the humble, soft-spoken Dunn as the pipe-smoking bassist of the Blues Brothers Band, who not only played with them on Saturday Night Live, but was a featured in the two movies. Others may be under the mistaken impression he was the guy playing the funky, bluesy bass on Booker T. and the MG’s first hit, Green Onions. (He wasn’t. He joined the band a year after the song was released.) But who Duck Dunn was, was one of the most anonymous great musicians of his or any other time, and an entirely self-taught bassist whose brilliance was measured not so much by the notes he played but by the company he kept. (When you get a chance, search the phrase “Duck Dunn discography,” and then sit back and prepare to be amazed.)

It would be tempting at this point to single out some shining moment like his interplay with the seagull effects on Redding’s (Sittin’ on the) Dock of  the Bay, or the way his bass powers Pickett’s Mustang Sally like a broad-shouldered, well-oiled and low-rumbling slant six. But instead, let me leave you with a song that, at least for me, captures his genius perfectly, Sam and Dave’s version of the minor Isaac Hayes/Dave Porter classic, I Thank You, two and a half minutes worth of vintage Memphis Soul and a song built almost entirely on Dunn's simple but powerful two (and maybe three) note bass line. Sure, other more celebrated rock bassists often played louder, faster, more nimbly, or certainly more conspicuously than Duck Dunn. But none of them understood any better that, as a bassist, when it comes to funk, soul and R&B, greatness is often achieved by all the things you don’t do.

the Bay, or the way his bass powers Pickett’s Mustang Sally like a broad-shouldered, well-oiled and low-rumbling slant six. But instead, let me leave you with a song that, at least for me, captures his genius perfectly, Sam and Dave’s version of the minor Isaac Hayes/Dave Porter classic, I Thank You, two and a half minutes worth of vintage Memphis Soul and a song built almost entirely on Dunn's simple but powerful two (and maybe three) note bass line. Sure, other more celebrated rock bassists often played louder, faster, more nimbly, or certainly more conspicuously than Duck Dunn. But none of them understood any better that, as a bassist, when it comes to funk, soul and R&B, greatness is often achieved by all the things you don’t do.

8. Marvin Miller

8. Marvin Miller

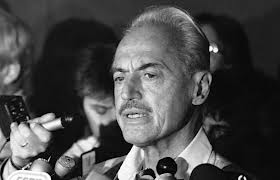

At first blush, Miller might be thought of as the guy who turned our national pastime on its ear four decades ago as the legal mind behind Curt Flood’s brash, historic and ultimately failed attempt to overturn baseball’s reserve clause. But Miller’s legacy was far more complex than lighting the fuse on the free agency era or creating the MLB Players Association. Drill down a bit and what you’ll find is, arguably, one of the seminal figures in baseball history, right up there alongside A.G. Spalding, Ban Johnson, Babe Ruth,  Bill Veeck, Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey. In fact, if you were to distill the history of the game into five seismic moments, you would probably pick its creation, its first night game, the breaking of its color line, the onset of free agency and the explosion of subscription TV. And Miller was the only guy whose fingerprints were all over at least two of those.

Bill Veeck, Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey. In fact, if you were to distill the history of the game into five seismic moments, you would probably pick its creation, its first night game, the breaking of its color line, the onset of free agency and the explosion of subscription TV. And Miller was the only guy whose fingerprints were all over at least two of those.

But beyond that, drill down even further and what you’ll find is a union advisor who in later years held the utterly indefensible position that steroids and performance enhancing drugs were not a union issue, and that testing for banned substances had no part in the game. And that’s  the point at which Miller’s long and deeply rooted legacy begins to grow cloudy. Because while Miller turned out to be a great legal mind and a brilliant tactician, he also proved to be a man blinded by ideological zeal and fueled by an almost pathological desire to further his agenda, regardless of price.

the point at which Miller’s long and deeply rooted legacy begins to grow cloudy. Because while Miller turned out to be a great legal mind and a brilliant tactician, he also proved to be a man blinded by ideological zeal and fueled by an almost pathological desire to further his agenda, regardless of price.

Forget that steroids were shattering forever many of the benchmarks that helped define the game in which his members were making their millions, many of them time-tested numbers which had given baseball a series of historical touchstones that would allow one generation after another of ticket-buying fans to unite and bond. Forget that steroids may have been jeopardizing the health, if not the very lives, of those taking them – all of whom were dues-paying members. And forget that by ingesting steroids and other PEDs, legal or otherwise, many of the most established members of the MLBPA were denying jobs and livelihoods to countless, clear-eyed and determined kids who refused to take them. At some point Miller’s mission seemed to be about two things and two things only; unfettered freedom for his members and unlimited money for their bank accounts.

That’s why Miller remains both a historically significant and a deeply flawed character. Because while he gave rise to a vitally important union that supported a highly moral and even righteous cause, one that would forever change the game’s history and its economic makeup, he ended up lending advise and counsel to what amounted to a professional guild driven almost exclusively by self-interest, short-term thinking and greed. Because what he had started so many years ago as a brotherhood to protect the weakest and most vulnerable, at some point crossed over and began operating solely in the interests of its richest and most powerful.

That’s why Miller remains both a historically significant and a deeply flawed character. Because while he gave rise to a vitally important union that supported a highly moral and even righteous cause, one that would forever change the game’s history and its economic makeup, he ended up lending advise and counsel to what amounted to a professional guild driven almost exclusively by self-interest, short-term thinking and greed. Because what he had started so many years ago as a brotherhood to protect the weakest and most vulnerable, at some point crossed over and began operating solely in the interests of its richest and most powerful.

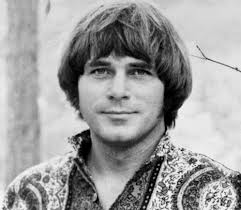

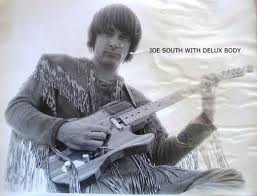

7. Joe South

7. Joe South

In many ways, the greatness of South as an artist might have perfectly captured by the handful of brawny, seductive and slightly ominous notes that as a young session guitarist he laid down at the very top of Aretha Franklin’s classic Chain of Fools. Listen to them. In those four seconds, South and the two lower strings of his guitar offer up what amounts to a clear shot over your bow – you know, just to get your attention. It is four seconds worth of musical bravado and sweaty, Southern in-your-faceness that in one sense seems oddly disjointed from the rest of the song, but in another utterly defines it; four seconds worth of muscle, grit and attitude that demand you stop whatever you’re doing and pay attention…or  else. Heck, South may just as well have bitch-slapped you across the face and snarled, “Shut the f*** up, and listen. This here’s the Queen of Soul.”

else. Heck, South may just as well have bitch-slapped you across the face and snarled, “Shut the f*** up, and listen. This here’s the Queen of Soul.”

Long before the image of a young rebel/poet with a guitar strapped over his shoulder became something of an American icon, there was Joe South walking the streets of Atlanta and playing anywhere and everywhere he could. At 15 years old he even scored his own morning radio show during which, at 6:00 am every Saturday, come rain or shine, he – and only he – would talk, tell stories and play his songs for the farmers milking their cows.

As he got older South turned to songwriting, though no singer ever seemed to be able to capture a Joe South song quite the way Joe South could. In Deep Purple’s hands, for example, the title word of his song Hush almost seems like filler; something plugged in at various points throughout the tune only because a one-syllable word seems to be in order.  When South sings that word, on the other hand, “hush” becomes a command. It becomes a order; one that carries with it implied consequences. Or when Lynn Anderson sings, “I beg your pardon, I never promised you a rose garden,” the line seems little more than cute sentiment or a slightly witty rhyme. But when South sings those words, they drip with some brutal mix of truth and irony. And in Billy Joe Royal’s hands, Down in the Boondocks feels like just another pop tune with a contrived conceit. But when South tells the story of two lovers from opposite sides of the tracks, it sounds as real and as sun-baked as Faulkner.

When South sings that word, on the other hand, “hush” becomes a command. It becomes a order; one that carries with it implied consequences. Or when Lynn Anderson sings, “I beg your pardon, I never promised you a rose garden,” the line seems little more than cute sentiment or a slightly witty rhyme. But when South sings those words, they drip with some brutal mix of truth and irony. And in Billy Joe Royal’s hands, Down in the Boondocks feels like just another pop tune with a contrived conceit. But when South tells the story of two lovers from opposite sides of the tracks, it sounds as real and as sun-baked as Faulkner.

Joe South eventually moved out from the shadows and onto center stage, and for two years he seemed to be everywhere, from the pop charts and country stations, to the weekly variety shows. In 1969, his Games People Play became a Top Ten hit and earned him two Grammy Awards, including one for Song of the Year. And his Walk a Mile in My Shoes, released shortly thereafter, was met with only slightly less commercial and critical acclaim. Joe South was on fire.

But then – poof – as quickly as it came, it was over. Some claim it was his drug use, including heroin. Others blame it on his reaction to his brother’s sudden suicide. Regardless, South’s behavior grew erratic and he became testy with fans and ugly to those around him. Eventually he withdrew altogether. One story even had him living for a while in the jungles of Hawaii. Whether fact or fiction, this much cannot be disputed: at the peak of his fame Joe South simply stopped making music. Oh, he released a hodgepodge of rambling, barely coherent songs a few years later, but that album went nowhere, and did so on its own merits – or lack thereof.

But then – poof – as quickly as it came, it was over. Some claim it was his drug use, including heroin. Others blame it on his reaction to his brother’s sudden suicide. Regardless, South’s behavior grew erratic and he became testy with fans and ugly to those around him. Eventually he withdrew altogether. One story even had him living for a while in the jungles of Hawaii. Whether fact or fiction, this much cannot be disputed: at the peak of his fame Joe South simply stopped making music. Oh, he released a hodgepodge of rambling, barely coherent songs a few years later, but that album went nowhere, and did so on its own merits – or lack thereof.

As far as Joe South’s creative decline goes, I can’t say for sure what brought it on. I only know this; that the man committed the greatest sin a guy in his line of work could ever commit. He just faded away. Whereas gone-before-their-time rockers like Janis Joplin, Kurt Cobain and Richie Valens, to name just a few – artists whose lives were cut short at the very peak of their fame – who continue to receive acclaim and be remembered in a way that, just maybe, exceeds their actual talent, South was just the opposite. His talent was enormous, and yet when he passed a few months back – some four decades after the peak of his relevance – there was barely a ripple of attention paid to it, or his legacy. That’s so sad, because as great a singer as Joe South was, he was even a better guitar player. And as great a guitarist as he was, he was an  even greater songwriter.

even greater songwriter.

You see, when he was in full control, Joe South didn’t just write songs, he composed them. And before his muse deserted him he was, in the tradition of celebrated wordsmiths like Faulkner, Robert Penn Warren, Eudora Welty and Harper Lee, a Southerner who could find in his place of birth deep, lasting and universal truths. His South was not the South of tractor pulls, mullets and oversized belt buckles. It was a lyrical South and a sepia-colored South; a South full of red dirt farms, swimming holes, barefoot girls, and giant oak trees teeming with chirping cicadas and dripping with long, languid strands of Spanish moss. That’s why as a songwriter, he had more in common with, say, Stephen Foster, Harlan Howard or Hank Williams than he did with so many of his rock contemporaries.

That’s also why when I had heard he died I went home and put on his, Don’t It Make You Want to Go Home, a stunningly lyrical paean to the land, the innocence and the memories of his boyhood Georgia, and a song which marries rock and gospel as well as any I’ve ever heard. Joe South may have passed virtually unnoticed in 2012. But do yourself a favor. Listen once again to him when, as a young man full of spit, fire and vinegar, he kicked open the damn door on Chain of Fools with four seconds worth of some of the most masculine, cocksure and ballsy guitar ever committed to vinyl – and this time do it closely. In those four seconds, along with the two or so minutes that follow, you will not only get to taste Joe South’s greatness, you’ll find yourself a perfect metaphor for how excruciatingly brief it was.

That’s also why when I had heard he died I went home and put on his, Don’t It Make You Want to Go Home, a stunningly lyrical paean to the land, the innocence and the memories of his boyhood Georgia, and a song which marries rock and gospel as well as any I’ve ever heard. Joe South may have passed virtually unnoticed in 2012. But do yourself a favor. Listen once again to him when, as a young man full of spit, fire and vinegar, he kicked open the damn door on Chain of Fools with four seconds worth of some of the most masculine, cocksure and ballsy guitar ever committed to vinyl – and this time do it closely. In those four seconds, along with the two or so minutes that follow, you will not only get to taste Joe South’s greatness, you’ll find yourself a perfect metaphor for how excruciatingly brief it was.

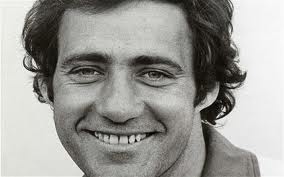

6. Georgio Chinaglia

6. Georgio Chinaglia

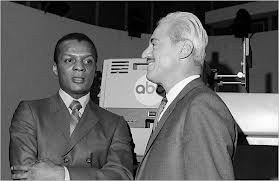

To know about Chinaglia, perhaps the seminal figure in the long and bumpy history of soccer as an official U.S. sport, it’s probably important to also know a little something about Steve Ross, the media visionary and former head of Warner Communications who brought him here. Ross was the guy who first conceived of the radical concept of  narrowcasting; TV networks designed to match subsets of the viewing public. That groundbreaking idea soon led to the birth of nets like Nickelodeon and, more famously, MTV. Ross also dreamed up a user-driven concept called interactive TV, a modern incarnation of which is now known to millions as On Demand.

narrowcasting; TV networks designed to match subsets of the viewing public. That groundbreaking idea soon led to the birth of nets like Nickelodeon and, more famously, MTV. Ross also dreamed up a user-driven concept called interactive TV, a modern incarnation of which is now known to millions as On Demand.

In the early 70s, Steve Ross had decided to purchase Atlantic Records, and during the due-diligence became friends with Nesuhi and Ahmet Ertegun, the legendary label’s co-founders – and, as it turned out, two wildly rabid soccer fans. Through the two, Ross began to  realize the enormous potential of soccer as a pro sport. So he spearheaded the formation of the North American Soccer League, and launched its flagship franchise, the New York Cosmos. Never one to do things in a small way, he then went out and signed Brazilian star and soccer immortal, Pele, the most famous athlete in the world, followed by West German great, Franz Beckenbauer. Both men, however, though popular attractions, were far from great players anymore.

realize the enormous potential of soccer as a pro sport. So he spearheaded the formation of the North American Soccer League, and launched its flagship franchise, the New York Cosmos. Never one to do things in a small way, he then went out and signed Brazilian star and soccer immortal, Pele, the most famous athlete in the world, followed by West German great, Franz Beckenbauer. Both men, however, though popular attractions, were far from great players anymore.

So Ross upped the ante. He went out and targeted a true soccer superstar to bring to New York, setting his sights on an Italian  heartthrob and renowned wild child named Georgio Chinaglia; at that point the greatest, most dynamic and most beloved athlete in Italy, and a powerful and fiercely talented young man at the very top of his game. When Chinaglia finally signed with the Cosmos, the news so stunned Italian football fans that at one point a number of them, including scores of adoring women, threatened to lie down in front of his plane’s wheels rather than let their much-adored disco-dancing, hard-drinking and skirt-chasing idol leave. But New York was calling. And what’s more, New York was about to fall in love, and Chinaglia was about to return the favor.

heartthrob and renowned wild child named Georgio Chinaglia; at that point the greatest, most dynamic and most beloved athlete in Italy, and a powerful and fiercely talented young man at the very top of his game. When Chinaglia finally signed with the Cosmos, the news so stunned Italian football fans that at one point a number of them, including scores of adoring women, threatened to lie down in front of his plane’s wheels rather than let their much-adored disco-dancing, hard-drinking and skirt-chasing idol leave. But New York was calling. And what’s more, New York was about to fall in love, and Chinaglia was about to return the favor.

And when he put on his Cosmo uniform, it was, indeed, a marriage made in heaven. Ross bonded with Chinaglia like no player ever, and allowed him to get away with  things no other player was allowed to do. For instance, the star striker was so proud of his U.S. citizenship papers that for years he kept them hanging in his locker – right next to an open bottle of Chivas Regal, and would regularly show the two as evidence of how much he loved New York. And for Chinaglia there was no such thing as curfew, even on game night. Ross’ look-the-other-way attitude caused resentment among many of his superstar’s teammates, but the results were undeniable. A franchise that just a few years earlier couldn’t draw 4,000 to a tiny municipal stadium on Randall’s Island was suddenly drawing 48,000 screaming fanatics to the Meadowlands. And it wasn’t just immigrant soccer buffs filling those seats. Some of the biggest names in all of pop culture started getting caught up in Chinaglia-mania and became regulars at Cosmo matches; people like Barbra Streisand, Mick Jagger, Phil Collins, Robert Redford, Muhammad Ali, Quincy Jones, Andy Warhol, Henry Kissinger and Steven Spielberg.

things no other player was allowed to do. For instance, the star striker was so proud of his U.S. citizenship papers that for years he kept them hanging in his locker – right next to an open bottle of Chivas Regal, and would regularly show the two as evidence of how much he loved New York. And for Chinaglia there was no such thing as curfew, even on game night. Ross’ look-the-other-way attitude caused resentment among many of his superstar’s teammates, but the results were undeniable. A franchise that just a few years earlier couldn’t draw 4,000 to a tiny municipal stadium on Randall’s Island was suddenly drawing 48,000 screaming fanatics to the Meadowlands. And it wasn’t just immigrant soccer buffs filling those seats. Some of the biggest names in all of pop culture started getting caught up in Chinaglia-mania and became regulars at Cosmo matches; people like Barbra Streisand, Mick Jagger, Phil Collins, Robert Redford, Muhammad Ali, Quincy Jones, Andy Warhol, Henry Kissinger and Steven Spielberg.

Chinaglia not only made headlines off the field, he proved to be as good as advertised on it. In his New York career, he ended up scoring two or more goals 54 times, three or more goals 16 times, and once scored 7 goals in a playoff game. The brash, cocky midfielder in time became the greatest scorer in NASL history, and the league’s most indelible personality.

Chinaglia not only made headlines off the field, he proved to be as good as advertised on it. In his New York career, he ended up scoring two or more goals 54 times, three or more goals 16 times, and once scored 7 goals in a playoff game. The brash, cocky midfielder in time became the greatest scorer in NASL history, and the league’s most indelible personality.

Yes, soccer may never have caught on in this country the way Steve Ross thought and certainly hoped it would. But in his day the passionate and full-of-life Chinaglia made it matter. And over three decades later, it still does and then some. Soccer is here, and slowly but surely it continues to grow. And the one man fans of the sport have to thank for that is a guy who wasn’t even born here, yet moved here before his 30th birthday and never looked back; a guy who single-handedly lit a fire in many American hearts for the game that decades later still remains; and a guy who planted the seeds for what has since become a true American archetype; the soccer mom.

As the New York Times once wrote of Georgio Chinaglia, this country's first-ever soccer superstar, at the very height of his fame: ''When I go home over the George Washington Bridge,'' he says with visible emotion, ''I feel as if I've lived here all my life. The rest is like a film. Like when we play in Los Angeles. We return to the airport here, and I feel as if I can breathe again, I'm home.''

As the New York Times once wrote of Georgio Chinaglia, this country's first-ever soccer superstar, at the very height of his fame: ''When I go home over the George Washington Bridge,'' he says with visible emotion, ''I feel as if I've lived here all my life. The rest is like a film. Like when we play in Los Angeles. We return to the airport here, and I feel as if I can breathe again, I'm home.''