Below, please enjoy part three of my four part tribute to those we lost this year whose deaths and legacies were largely overlooked, or at least under-reported, by the mainstream media.

21. Helen Gurley Brown

In one sense she was just like so many others girls her age. Born in Arkansas in the 20s; raised in both California and Georgia; attended schools like Texas College for Women and Woodbury Business College, where she dutifully honed her clerical skills; and got her start as an executive secretary at both a talent and advertising agency. But at the second of those is where she finally caught the break that would change her life. Just like Peggy Olson in Mad Men, someone at the agency recognized in young Miss Gurley her talent for words and made her a copywriter, something at which she not only excelled, but became hugely successful. Then in 1960, while toiling away after work

In one sense she was just like so many others girls her age. Born in Arkansas in the 20s; raised in both California and Georgia; attended schools like Texas College for Women and Woodbury Business College, where she dutifully honed her clerical skills; and got her start as an executive secretary at both a talent and advertising agency. But at the second of those is where she finally caught the break that would change her life. Just like Peggy Olson in Mad Men, someone at the agency recognized in young Miss Gurley her talent for words and made her a copywriter, something at which she not only excelled, but became hugely successful. Then in 1960, while toiling away after work  and on weekends, she finally finished the book that would light the fuse on the “sexual revolution.” That year, the now-married Gurley Brown published Sex and the Single Girl, a non-fiction account which encouraged women to become both financially independent and to experience a rich, full and, most of all, adventurous sex life. It was a self-help book like no self-help book ever and became a literary sensation that vaulted to the top of the New York Times best seller list, where it stayed for over a year. Three years later, Ms. Gurley Brown, then a household name, was named editor of Cosmopolitan and in short order turned the magazine into one that ripped sex out of the bedroom and splashed it all over the front page – not to mention inside, where it once ran a tasteful but tongue-in-cheek nude centerfold of hunky actor Burt Reynolds to tweak Playboy, a smart but slightly naughty magazine that regularly offered its male readers a centerfold of airbrushed, unclothed but idealized girl-next-door types.

and on weekends, she finally finished the book that would light the fuse on the “sexual revolution.” That year, the now-married Gurley Brown published Sex and the Single Girl, a non-fiction account which encouraged women to become both financially independent and to experience a rich, full and, most of all, adventurous sex life. It was a self-help book like no self-help book ever and became a literary sensation that vaulted to the top of the New York Times best seller list, where it stayed for over a year. Three years later, Ms. Gurley Brown, then a household name, was named editor of Cosmopolitan and in short order turned the magazine into one that ripped sex out of the bedroom and splashed it all over the front page – not to mention inside, where it once ran a tasteful but tongue-in-cheek nude centerfold of hunky actor Burt Reynolds to tweak Playboy, a smart but slightly naughty magazine that regularly offered its male readers a centerfold of airbrushed, unclothed but idealized girl-next-door types.  In time, Cosmo became the bible for the liberated woman and under Brown’s mentorship empowered the female of the species sexually like no publication, book, movie or TV show had ever done before, or frankly since. Eventually, Brown became recognized as a leader of the women’s lib movement and found herself often painted with the same broad brush as the likes of Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, Bella Abzug, Billie Jean King and many of the more humorless, prickly and even militant feminist icons of the day. But militant feminism was never Helen Gurley Brown’s game. Her game was sex; embracing it, exploring it, reveling in it, and ultimately becoming both liberated and empowered by it. Plus, no two ways about it; in her day she was as cute as a button and had more than her share of sex appeal.

In time, Cosmo became the bible for the liberated woman and under Brown’s mentorship empowered the female of the species sexually like no publication, book, movie or TV show had ever done before, or frankly since. Eventually, Brown became recognized as a leader of the women’s lib movement and found herself often painted with the same broad brush as the likes of Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, Bella Abzug, Billie Jean King and many of the more humorless, prickly and even militant feminist icons of the day. But militant feminism was never Helen Gurley Brown’s game. Her game was sex; embracing it, exploring it, reveling in it, and ultimately becoming both liberated and empowered by it. Plus, no two ways about it; in her day she was as cute as a button and had more than her share of sex appeal.  As a result, throughout her life and no matter where she went, she would use her brains, her looks and her feminine charms to their fullest advantage. And what’s more, unlike so many feminist contemporaries, she fully understood the power of humor and never met a quip she didn’t like. That’s why years ago Ms. Gurley Brown once told a writer with not only a wink and a smile, but a twinkle in her eye, “Good girls go to heaven. Bad girls go everywhere.”

As a result, throughout her life and no matter where she went, she would use her brains, her looks and her feminine charms to their fullest advantage. And what’s more, unlike so many feminist contemporaries, she fully understood the power of humor and never met a quip she didn’t like. That’s why years ago Ms. Gurley Brown once told a writer with not only a wink and a smile, but a twinkle in her eye, “Good girls go to heaven. Bad girls go everywhere.”

20. Fern Parsons

20. Fern Parsons

At first blush she was merely an under-employed actor who, frankly, did relatively little screen work in her seven decades. But she mattered and she’s on this list for two reasons. First, Parsons, who actually made her screen debut in a short for the original Mickey Mouse Club, spent her life a strident and feisty-as-hell union activist working on behalf of all actors, but especially older ones. When the Screen Actors Guild formed a chapter in her hometown of Chicago in 1955, she was fifth in line to join, and then sat on the SAG board both locally and nationally on and off for the next 44 years. Decades later, when a production company sought to use non-union actors  while the union players were out on strike, a riled-up Parsons grabbed a sign and defiantly joined the picket line – at 90 years of age. But more than her activism, Fern Parsons is on this list for two movies. If women have their Beaches, Terms of Endearment, and Sleepless in Seattle, men have their guilty pleasures too; particularly two tug-at-your-heart, male-targeted weepers; Field of Dreams and Hoosiers -- and Parsons stars in both of them. In the former she's

while the union players were out on strike, a riled-up Parsons grabbed a sign and defiantly joined the picket line – at 90 years of age. But more than her activism, Fern Parsons is on this list for two movies. If women have their Beaches, Terms of Endearment, and Sleepless in Seattle, men have their guilty pleasures too; particularly two tug-at-your-heart, male-targeted weepers; Field of Dreams and Hoosiers -- and Parsons stars in both of them. In the former she's  Kevin Costner’s stern and utterly humorless mother-in-law who, with her son, cannot see the ballplayers on Ray’s field. In the latter, she’s virtually the opposite. Parsons plays Barbara Hershey’s down-home and spunky mother, Opal, who spontaneously stands and suggests a recount at the town hall meeting to determine the fate of Coach Dale, and who earlier in the film prefaces her dinner invite to the man with the memorable and deliciously earthy line, Sun don't shine on the same dog's ass every day. But, mister, you ain't seen a ray of light since you got here.

Kevin Costner’s stern and utterly humorless mother-in-law who, with her son, cannot see the ballplayers on Ray’s field. In the latter, she’s virtually the opposite. Parsons plays Barbara Hershey’s down-home and spunky mother, Opal, who spontaneously stands and suggests a recount at the town hall meeting to determine the fate of Coach Dale, and who earlier in the film prefaces her dinner invite to the man with the memorable and deliciously earthy line, Sun don't shine on the same dog's ass every day. But, mister, you ain't seen a ray of light since you got here.

19. Hal David

19. Hal David

The man who, just maybe, asked more musical questions than any songwriter in history. "Do you know the way to San Jose?" "What’s it all about, Alfie?" "What do you get when you fall in love?" And, of course; "What’s new pussycat?" As the longtime lyricist for legendary composer Burt Bacharach, the two made music for a relatively brief time in the 1960s that, by all rights, could have been – and probably should have – considered trite or passé, especially in light of so many of the far cooler and more youth-driven musical trends of the era; the British Invasion, garage punk, rock operas, power pop, surf music, folk rock, psychedelia, and even the first, faint rumblings of heavy metal. Yet Bacharach and David found a way to matter during that cosmic and trippy age because even back then they were recognized as brilliant and possibly even timeless songwriters – especially when interpreted by a soulful young diva named Dionne Warwick. The genius of Hal David can  probably best distilled in one story. In his Upper West Side apartment one evening, Bacharach was working on song he had built around a somber, slow-building and ultimately wildly dramatic melody, and played it for Warwick who happened to stop by. The singer went crazy over the song, and excitedly urged the two to finish it so she could give it a whirl. So David took the melody as written into the bedroom, worked on it for a half an hour or so, and came out with the lyrics fully written and the song finished. And in that amount of time, he composed a set of lyrics to a collection of notes and phrases that, even now, almost seem to defy words. Yet the song Hal David was able to finish that night in a matter of minutes remains to this day one of the most

probably best distilled in one story. In his Upper West Side apartment one evening, Bacharach was working on song he had built around a somber, slow-building and ultimately wildly dramatic melody, and played it for Warwick who happened to stop by. The singer went crazy over the song, and excitedly urged the two to finish it so she could give it a whirl. So David took the melody as written into the bedroom, worked on it for a half an hour or so, and came out with the lyrics fully written and the song finished. And in that amount of time, he composed a set of lyrics to a collection of notes and phrases that, even now, almost seem to defy words. Yet the song Hal David was able to finish that night in a matter of minutes remains to this day one of the most  astounding marriages of music and language in the Burt Bacharach canon, as well as one of the soulful and stirring ballads of all time. What’s more, it remains a song in which Bacharach’s partner-in-words poses not one, but two of his trademark questions; "What am I to do?"...and a far more impassioned, heart-felt and gut-wrenchingly honest one with which he ends it; "Anyone who had a heart would surely take me in his arms and love me…why won’t you?"

astounding marriages of music and language in the Burt Bacharach canon, as well as one of the soulful and stirring ballads of all time. What’s more, it remains a song in which Bacharach’s partner-in-words poses not one, but two of his trademark questions; "What am I to do?"...and a far more impassioned, heart-felt and gut-wrenchingly honest one with which he ends it; "Anyone who had a heart would surely take me in his arms and love me…why won’t you?"

18. Bob Stewart

18. Bob Stewart

One day Bob Stewart ran into a young announcer named Monty Hall on the street, who would soon go on to fame and fortune as host of Let’s Make a Deal. Hall, who knew the attorney at a new company headed up by daytime TV producers Mark Goodson and Bill Todman, and who had just come from the company’s offices, said to Stewart, “You got any ideas?” Stewart did indeed have an idea. He had watched an auction one afternoon at lunch and got the idea for a show called The Auctioneer. Stewart eventually went to work for Goodson-Todman and eventually turned The Auctioneer into a show hosted by Bill Cullen that he would call The Price is Right. Later, Stewart  conceived a game hosted by newsman Mike Wallace that for its pilot was shot under the working title, Nothing but the Truth. Wallace would eventually get replaced by Bud Collyer and the show re-christened To Tell the Truth. Later still, the young producer created a word-association game he built around celebrity contestants and a concept he’d been kicking around in his brain for a while called a “lightning round.” Stewart called his new show Password. And later still, then as an independent producer, he conceived a game that once again featured celebrity contestants and once again relied on word association. He called his little concoction, The $10,000 Pyramid.

conceived a game hosted by newsman Mike Wallace that for its pilot was shot under the working title, Nothing but the Truth. Wallace would eventually get replaced by Bud Collyer and the show re-christened To Tell the Truth. Later still, the young producer created a word-association game he built around celebrity contestants and a concept he’d been kicking around in his brain for a while called a “lightning round.” Stewart called his new show Password. And later still, then as an independent producer, he conceived a game that once again featured celebrity contestants and once again relied on word association. He called his little concoction, The $10,000 Pyramid.  Yes, they were only game shows. Yes, they were inconsequential. And yes, they could at times seem downright mindless. But to argue game show pioneer Bob Stewart didn’t fundamentally change pop culture in this country is to contend that the guy who invented, say, the drive-thru window, the hot dog bun, or the vending machine didn’t somehow along the way also radically alter the very nature of how and when America feeds itself.

Yes, they were only game shows. Yes, they were inconsequential. And yes, they could at times seem downright mindless. But to argue game show pioneer Bob Stewart didn’t fundamentally change pop culture in this country is to contend that the guy who invented, say, the drive-thru window, the hot dog bun, or the vending machine didn’t somehow along the way also radically alter the very nature of how and when America feeds itself.

17. Sylvia Woods

17. Sylvia Woods

Aretha Franklin may be the “Queen of Soul,” but Woods was the undisputed “Queen of Soul Food.” As matron and chief cook of a restaurant she founded with husband, Herbert, in 1962 near the corner of 127th Street and Lennox Ave in the heart of Harlem, Woods not only made great mouth-watering soul food accessible to everyone, she used her delicious brand of southern-style cooking as a way to tear down walls and bring people together, regardless of who they were, what they did, what they earned, what color they were, or who they prayed to. Born to a dirt-poor family from rural South Carolina in 1926, Sylvia Woods met her husband and love of her life while working side by side with him,  picking beans under the hot sun. She was 11 years old and he was 12. Later he followed her to New York, where she found work as a waitress. Sylvia’s first day on that waitressing job also turned out to be her very first time in a restaurant. A few years later she opened Sylvia’s. At the time, her little restaurant had just six tables and 15 stools. Yet, she soon found the world beating a path to her door, fueled by her lip-smacking, finger-licking mix of ribs, fried chicken and catfish, black-eyed peas, fried okra, collard greens, sweet tea and, of course, fresh-from-the-oven corn bread. Before long, Sylvia’s humble little restaurant was teeming with everyone from headliners at the nearby Apollo to a succession of residents of Gracie Mansion; mayors like David Dinkins, Ed Koch, Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg. When Nelson Mandela came to town, he ate there. Caroline Kennedy ate there. Magic Johnson ate there; so did Russell Simmons. Jann Wenner said Ahmet Ertegun used to love

picking beans under the hot sun. She was 11 years old and he was 12. Later he followed her to New York, where she found work as a waitress. Sylvia’s first day on that waitressing job also turned out to be her very first time in a restaurant. A few years later she opened Sylvia’s. At the time, her little restaurant had just six tables and 15 stools. Yet, she soon found the world beating a path to her door, fueled by her lip-smacking, finger-licking mix of ribs, fried chicken and catfish, black-eyed peas, fried okra, collard greens, sweet tea and, of course, fresh-from-the-oven corn bread. Before long, Sylvia’s humble little restaurant was teeming with everyone from headliners at the nearby Apollo to a succession of residents of Gracie Mansion; mayors like David Dinkins, Ed Koch, Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg. When Nelson Mandela came to town, he ate there. Caroline Kennedy ate there. Magic Johnson ate there; so did Russell Simmons. Jann Wenner said Ahmet Ertegun used to love  Sylvia’s, and before the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction one year treated 20 or so R&B legends, including Solomon Burke, to break bread with him there. Quincy Jones and Ashley Judd ate there. When Bill O’Reilly and Al Sharpton wanted to sit down and hash out their differences over lunch, they did so at one of Sylvia’s corner tables. But perhaps the most celebrated regular of all was one of the most notorious soul food lovers to ever feel someone’s pain; the man many claim was this nation’s real first black president. Bill Clinton not only used to regularly walk to Sylvia’s for lunch from his office on 125th, but when she died earlier this year he reached out to her children and asked to speak

Sylvia’s, and before the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction one year treated 20 or so R&B legends, including Solomon Burke, to break bread with him there. Quincy Jones and Ashley Judd ate there. When Bill O’Reilly and Al Sharpton wanted to sit down and hash out their differences over lunch, they did so at one of Sylvia’s corner tables. But perhaps the most celebrated regular of all was one of the most notorious soul food lovers to ever feel someone’s pain; the man many claim was this nation’s real first black president. Bill Clinton not only used to regularly walk to Sylvia’s for lunch from his office on 125th, but when she died earlier this year he reached out to her children and asked to speak  at their mother’s memorial. Not bad for a little southern girl and former bean picker who ventured north to Harlem just as one of the most volatile, racially charged eras in this country’s history was about to unfold, and who then proceeded to wage a one-woman war against hatred, intolerance, cruelty and ignorance by cooking with love, trafficking in humanity, and whenever someone set foot in her little soul food restaurant – regardless of who they were, or where they came from – embracing them like family.

at their mother’s memorial. Not bad for a little southern girl and former bean picker who ventured north to Harlem just as one of the most volatile, racially charged eras in this country’s history was about to unfold, and who then proceeded to wage a one-woman war against hatred, intolerance, cruelty and ignorance by cooking with love, trafficking in humanity, and whenever someone set foot in her little soul food restaurant – regardless of who they were, or where they came from – embracing them like family.

16. Steve Sabol

16. Steve Sabol

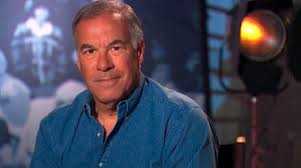

The man who changed forever how we watch, and perhaps more importantly, how we describe sports on television. As the son of the founder of NFL Films, Sabol – even more than Pete Rozelle, long considered the Moses of the NFL, and even more than the Colts’ sudden death win over the Giants in the ’58 NFL Championship, which hurled the league headlong into the  television era – was the guy whose ability to marry poetic and stirring words with hyper-dramatic and often slow motion shots of football players, coaches and fans fundamentally and almost singularly branded the NFL, searing it into our collective consciousness, and elevating it into something akin to gallant, noble, almost death-defying gladiator warfare. And you see; even there, homage was being paid the remarkable legacy of Steve Sabol. Because, as a young man fresh out of college, he began writing highly dramatic scripted narrations for his father’s

television era – was the guy whose ability to marry poetic and stirring words with hyper-dramatic and often slow motion shots of football players, coaches and fans fundamentally and almost singularly branded the NFL, searing it into our collective consciousness, and elevating it into something akin to gallant, noble, almost death-defying gladiator warfare. And you see; even there, homage was being paid the remarkable legacy of Steve Sabol. Because, as a young man fresh out of college, he began writing highly dramatic scripted narrations for his father’s  packages of video game stories, highlights and blooper reels that dusted off and put into use a kind of over-wrought language that had long been dormant in sports reporting; a language that traded heavily on muscular, often melodramatic prose, classical references, and perhaps most of all, military imagery – all, of course, delivered in deep, dulcet and deadly serious, voice-of-God tones. And to watch the story of even an inconsequential game on NFL Films, especially in Sabol’s hands, was in many ways to watch it for the very first time – even if you happened to be there, live and in person. The man wasn’t perfect, of course. His film of Super Bowl III -- in which Joe Namath’s lowly Jets of the upstart AFL stunned the daunting and heavily favored Colts of the NFL -- told a

packages of video game stories, highlights and blooper reels that dusted off and put into use a kind of over-wrought language that had long been dormant in sports reporting; a language that traded heavily on muscular, often melodramatic prose, classical references, and perhaps most of all, military imagery – all, of course, delivered in deep, dulcet and deadly serious, voice-of-God tones. And to watch the story of even an inconsequential game on NFL Films, especially in Sabol’s hands, was in many ways to watch it for the very first time – even if you happened to be there, live and in person. The man wasn’t perfect, of course. His film of Super Bowl III -- in which Joe Namath’s lowly Jets of the upstart AFL stunned the daunting and heavily favored Colts of the NFL -- told a  story with an almost toxic level of NFL bias, greatly embellished the role that substitute quarterback and Sabol favorite, Johnny Unitas, played in the game, and let one of the great sports upsets of all time slip into history woefully mis-documented. But when he was good, there were truly none better. Even today, to listen to his words unfold over cameraman Phil Tuckett’s electrifying, almost spine-tingling shot of John Riggins’ face as the exhausted but fiercely determined running back rumbles toward the goal line – directly at the camera – puffing his way to a stunning, game-altering 43-yard touchdown in the closing moments of Super Bowl XLVII is to witness one of the greatest moments ever achieved in television sports production. And following the now-legendary “Ice Bowl” between the Packers and the Cowboys on New Year’s Eve 1967, Steve Sabol and his typewriter not only helped turn an anonymous offensive lineman who made a single key block,

story with an almost toxic level of NFL bias, greatly embellished the role that substitute quarterback and Sabol favorite, Johnny Unitas, played in the game, and let one of the great sports upsets of all time slip into history woefully mis-documented. But when he was good, there were truly none better. Even today, to listen to his words unfold over cameraman Phil Tuckett’s electrifying, almost spine-tingling shot of John Riggins’ face as the exhausted but fiercely determined running back rumbles toward the goal line – directly at the camera – puffing his way to a stunning, game-altering 43-yard touchdown in the closing moments of Super Bowl XLVII is to witness one of the greatest moments ever achieved in television sports production. And following the now-legendary “Ice Bowl” between the Packers and the Cowboys on New Year’s Eve 1967, Steve Sabol and his typewriter not only helped turn an anonymous offensive lineman who made a single key block,  Jerry Kramer, into something of a star, if not a household name, in the process he conceived, coined and introduced to the football-loving public one of the most iconic, descriptive, oft-repeated, corny, yet beloved phrases in the history of American sports: frozen tundra.

Jerry Kramer, into something of a star, if not a household name, in the process he conceived, coined and introduced to the football-loving public one of the most iconic, descriptive, oft-repeated, corny, yet beloved phrases in the history of American sports: frozen tundra.

15. Phyllis Diller

15. Phyllis Diller

There was any number of women doing comedy before Phyllis Diller, of course. From film legends like Margaret Dumont, of Marx Brothers fame, Rosalind Russell, Mae West and Judy Holliday, to TV greats like Lucille Ball and Audrey Meadows, and even skit pioneers like Imogene Coca and Elaine May; the history of American comedy is littered with funny women who could, and often would, stop at nothing to get a laugh. But the thing one that separated Diller from all those others is that none of them ever did standup; none ever worked an audience or a room alone, armed with little more than a spotlight, a microphone, and a few jokes she had written rattling around in her brain. And that’s why Diller matters, and that’s why she’s earned a place on this list. Along with salty and sassy African-American comic legend Moms Mabley, who was carving out a niche for herself doing  standup on the old Chitlin’ Circuit, Phyllis Diller, a contemporary of Mabley’s, was likewise clearing a path for women comics that, frankly, had never existed until one day in the early 1950s the young St. Louis housewife decided to tease her hair into an unruly mess, put on a loud, garish dress, don some heavy makeup, grab a cigarette holder, and stride out onstage in a small club, all sassy and full of self-effacing charm; a club, mind you, that until that point always been the exclusive domain of male comics. What’s more, in one of the loneliest, most unforgiving and most deeply personal of all the performing arts, she doubled down that day by making herself the butt of her own jokes. Who else but a brave and daring young woman, even a comic, would ever

standup on the old Chitlin’ Circuit, Phyllis Diller, a contemporary of Mabley’s, was likewise clearing a path for women comics that, frankly, had never existed until one day in the early 1950s the young St. Louis housewife decided to tease her hair into an unruly mess, put on a loud, garish dress, don some heavy makeup, grab a cigarette holder, and stride out onstage in a small club, all sassy and full of self-effacing charm; a club, mind you, that until that point always been the exclusive domain of male comics. What’s more, in one of the loneliest, most unforgiving and most deeply personal of all the performing arts, she doubled down that day by making herself the butt of her own jokes. Who else but a brave and daring young woman, even a comic, would ever  stand in front of a group of strangers and announce, “My body's in such bad shape I wear prescription underwear?" Or shamelessly talk about her miserable sex life with her fictional husband Fang by claiming, “His finest hour lasted a minute and a half?” Or tell about the time she ran to the curb in her nightgown just as the truck was pulling away and asked the driver, “Am I too late for the garbage?” only have him reply, “No, hop in?” Whether or not you liked her, or deemed her particularly funny, is really immaterial. What matters, and why she's on this list, is one simple fact. If you were to trace a line backwards from Tig Notaro, through the likes of Sarah Silverman, Margaret Cho, Tracey Ullman, Roseanne Barr, Ellen DeGeneres, Whoopi Goldberg, Lily Tomlin and even Joan Rivers, that line would trace all the way back to – and form immediately behind – a gutsy and refreshingly self-effacing one-time housewife named Phyllis Diller.

stand in front of a group of strangers and announce, “My body's in such bad shape I wear prescription underwear?" Or shamelessly talk about her miserable sex life with her fictional husband Fang by claiming, “His finest hour lasted a minute and a half?” Or tell about the time she ran to the curb in her nightgown just as the truck was pulling away and asked the driver, “Am I too late for the garbage?” only have him reply, “No, hop in?” Whether or not you liked her, or deemed her particularly funny, is really immaterial. What matters, and why she's on this list, is one simple fact. If you were to trace a line backwards from Tig Notaro, through the likes of Sarah Silverman, Margaret Cho, Tracey Ullman, Roseanne Barr, Ellen DeGeneres, Whoopi Goldberg, Lily Tomlin and even Joan Rivers, that line would trace all the way back to – and form immediately behind – a gutsy and refreshingly self-effacing one-time housewife named Phyllis Diller.

14. Jon Lord

14. Jon Lord

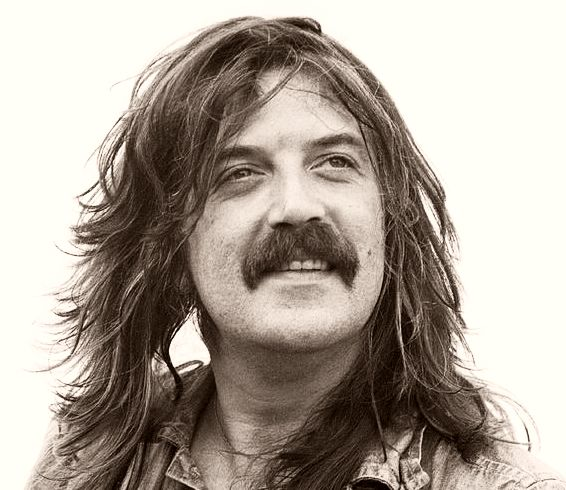

He wasn’t just the organist for Deep Purple; he was the man responsible for creating the full, ballsy, ferociously loud, and wickedly distorted sound that would become the calling card of Black Sabbath, Metallica, Led Zeppelin and just about every heavy metal band ever formed, along with the genre of music they played. Before there even was heavy metal, in fact, there was Deep Purple, a London-based quintet known for not only playing  at ear-splitting levels, but having two fabulously talented musicians; Ritchie Blackmore, the lead guitarist, and Lord, their organist. The two were steeped in jazz and used to love trading hot licks and jazzy

at ear-splitting levels, but having two fabulously talented musicians; Ritchie Blackmore, the lead guitarist, and Lord, their organist. The two were steeped in jazz and used to love trading hot licks and jazzy  solos back and forth with one another. The problem was Blackmore’s guitar was always being run through a large column amp while Lord’s Hammond C3 organ had only its smaller, less powerful and self-contained one. One day, Lord devised a way to wire his C3 through the same amp as Blackmore and, in essence, put his instrument on equal footing with the guitar. The result was a raucous and frenetic lo-fi sound that gave the

solos back and forth with one another. The problem was Blackmore’s guitar was always being run through a large column amp while Lord’s Hammond C3 organ had only its smaller, less powerful and self-contained one. One day, Lord devised a way to wire his C3 through the same amp as Blackmore and, in essence, put his instrument on equal footing with the guitar. The result was a raucous and frenetic lo-fi sound that gave the  band, especially live, a heightened sense of energy and even greater stage presence. And with that one innovation, the signature heavy metal sound that kids would be banging their heads to for generations was born. Yet even in the studio, that single tweak began manifesting itself in ways that people back then, and even now, didn’t fully appreciate. Every kid, for example, who ever picks up a guitar invariably tries to learn Blackmore’s indelible three-chord riff that opens Smoke on the Water, hoping against hope to not only play it like him, but sound like him. What

band, especially live, a heightened sense of energy and even greater stage presence. And with that one innovation, the signature heavy metal sound that kids would be banging their heads to for generations was born. Yet even in the studio, that single tweak began manifesting itself in ways that people back then, and even now, didn’t fully appreciate. Every kid, for example, who ever picks up a guitar invariably tries to learn Blackmore’s indelible three-chord riff that opens Smoke on the Water, hoping against hope to not only play it like him, but sound like him. What  they don’t realize is that directly under Blackmore’s guitar in that opening is Lord’s organ, playing the exact same chords, and being run through the exact same amp. And it’s the powerful combination of those two instruments that makes that riff stand out and why people still point to it as one of the two or three defining “guitar” riffs in the history of rock. But if Jon Lord had never done anything else in his life other than play the slow-to-boil but eventually soaring solo that begins at around the 2:45 mark of Deep Purple’s version of Hush – the single most incredible rock and roll organ I’ve ever heard in my life; and yes, that includes Gimme Some Lovin’ and Like a Rollin’ Stone – well, that would have been alright by me.

they don’t realize is that directly under Blackmore’s guitar in that opening is Lord’s organ, playing the exact same chords, and being run through the exact same amp. And it’s the powerful combination of those two instruments that makes that riff stand out and why people still point to it as one of the two or three defining “guitar” riffs in the history of rock. But if Jon Lord had never done anything else in his life other than play the slow-to-boil but eventually soaring solo that begins at around the 2:45 mark of Deep Purple’s version of Hush – the single most incredible rock and roll organ I’ve ever heard in my life; and yes, that includes Gimme Some Lovin’ and Like a Rollin’ Stone – well, that would have been alright by me.

12. Dick Clark

12. Dick Clark

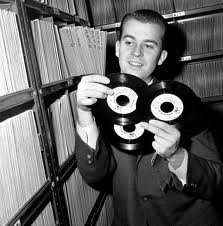

Talk about muddy legacies. And I’m not talking about his rather toothless New Year’s Eve specials or that mind-numbing series of blooper shows he produced and co-hosted with Ed McMahon. I’m talking about his rock 'n roll legacy. On one hand, Dick Clark was the guy in the 50s who scrubbed rock clean, dressed it up for its coming-out party, and introduced it for the first time to millions of kids and their parents across America, especially in suburbia. His American Bandstand, which was both a syndicated Philly show and, for a brief time, a New York-based network one, emerged as the single most important proving ground and an essential measuring stick for any rock, pop or soul act trying to make it in the music business. Appearing on Bandstand meant one of two things; a  band (or singer) had either hit the big time or, most likely, soon would. What’s more, the roster of musicians that appeared on Clark’s iconic and long-running weekly dance show reads like a Who’s Who of American pop culture. The list of names is so expansive, so eclectic, so multi-generational, and so star-studded it almost defies description. And it is impossible to tell the story of rock in American without a full chapter dedicated to Dick Clark and American Bandstand. But there was a dark side to Clark’s Bandstand days. As a shrewd businessman, he understood not only the power of his pulpit, but the value of securing publishing rights. And in the days before payola became not only illegal but scandalous, he regularly told bands, managers, and record companies that the only way he would play their song was if they assigned him 50% of its publishing rights. What’s more, he used to

band (or singer) had either hit the big time or, most likely, soon would. What’s more, the roster of musicians that appeared on Clark’s iconic and long-running weekly dance show reads like a Who’s Who of American pop culture. The list of names is so expansive, so eclectic, so multi-generational, and so star-studded it almost defies description. And it is impossible to tell the story of rock in American without a full chapter dedicated to Dick Clark and American Bandstand. But there was a dark side to Clark’s Bandstand days. As a shrewd businessman, he understood not only the power of his pulpit, but the value of securing publishing rights. And in the days before payola became not only illegal but scandalous, he regularly told bands, managers, and record companies that the only way he would play their song was if they assigned him 50% of its publishing rights. What’s more, he used to  barter playtime in exchange for a piece of so many record labels, and did that so frequently, that at one point prior to the payola hearings in the late 50s Dick Clark owned a piece of 33 different record labels. At those congressional hearings, before which he wisely divested himself of many of the assets he acquired in exchange for playing songs and booking bands, he was a humble, affable, well-mannered and respectful witness. As a result, he skated and avoided any retribution on the part of Congress; something that Alan Freed, perhaps the most powerful DJ of the day, who was also called to testify, but who proved to be a far more prickly and defiant witness, could not say. For that reason, while Clark went immediately back to work as “American’s oldest teenager,” Freed was fired by his station and soon found himself out of radio altogether and consigned to rock 'n roll history. Perhaps Dick Clark’s lasting and undeniable but nevertheless murky legacy was best summed up by songwriter and producer, Artie Singer, who once managed the old do-wop group, Danny and the Juniors. Singer told PBS once in a documentary

barter playtime in exchange for a piece of so many record labels, and did that so frequently, that at one point prior to the payola hearings in the late 50s Dick Clark owned a piece of 33 different record labels. At those congressional hearings, before which he wisely divested himself of many of the assets he acquired in exchange for playing songs and booking bands, he was a humble, affable, well-mannered and respectful witness. As a result, he skated and avoided any retribution on the part of Congress; something that Alan Freed, perhaps the most powerful DJ of the day, who was also called to testify, but who proved to be a far more prickly and defiant witness, could not say. For that reason, while Clark went immediately back to work as “American’s oldest teenager,” Freed was fired by his station and soon found himself out of radio altogether and consigned to rock 'n roll history. Perhaps Dick Clark’s lasting and undeniable but nevertheless murky legacy was best summed up by songwriter and producer, Artie Singer, who once managed the old do-wop group, Danny and the Juniors. Singer told PBS once in a documentary  about payola that while it hurt to sign over 50% of the rights to a song he had written, just to get it played, in the end he’d do it again because he owed his career to the deal. “It was bittersweet,” admitted Singer, “But I owe everything to him. Without (Dick Clark)…and without me saying ‘Here, take this (the money)’…there would have been no At the Hop…and there would have been no Danny and the Juniors.”

about payola that while it hurt to sign over 50% of the rights to a song he had written, just to get it played, in the end he’d do it again because he owed his career to the deal. “It was bittersweet,” admitted Singer, “But I owe everything to him. Without (Dick Clark)…and without me saying ‘Here, take this (the money)’…there would have been no At the Hop…and there would have been no Danny and the Juniors.”

11. Kitty Wells

11. Kitty Wells

She was to country music what the Phyllis Diller was to standup; a lady whose accomplishments as an artist, as great as they may have been, would in time find themselves overshadowed by the epic scope of the ground she broke. Before Kitty Wells – or to be more precise, before one particular song Kitty Wells recorded – a woman in country music was expected to be like so many expected her to be in the bedroom; passive, complementary and ready, willing and able to serve (or perhaps service) her man. In 1952, Hank Thompson had a #1 hit titled The Wild Side of Life, in which the singer’s young, night-loving “honky tonk angel” of a bride-to-be abandons him for a man she met in a roadhouse and crosses over to the “wild side of life.” The song, released in March of 1951, went so far as to imply that many of society’s ills are the fault of women. Three months later, Wells, a soft- spoken, God-fearing and polite wife and mother (she would stay married to her husband for 74 years), came out swinging with a song penned by Louisiana songwriter, Jay Miller. Wells’ song, sung to the same melody as Thompson’s, though at a slightly faster tempo, takes the perspective of a woman at a bar listening to Thompson’s original on the jukebox, who then bristles at its sentiments and contends she’s in a road house not because she wants to be, but because her cheating husband has compelled her to be. When Thompson’s sanctimoniously sings, “I didn’t know God man honky-tonk angels,” Wells throws it right back at him and warbles, “It wasn’t God who made honky tonk angels,” before adding, “Too many times married men think they're still single. And that's caused many a good girl to go wrong.” Wells’ in-your-face rebuttal, along with the simple but unapologetic way she delivered it, struck a chord with people, but especially women, who suddenly found themselves – and in many cases their home lives – represented as never before on the radio. “It Wasn't God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels” began selling as few country singles had ever sold. But not without controversy. It eventually got banned on radio stations throughout the country, as well

spoken, God-fearing and polite wife and mother (she would stay married to her husband for 74 years), came out swinging with a song penned by Louisiana songwriter, Jay Miller. Wells’ song, sung to the same melody as Thompson’s, though at a slightly faster tempo, takes the perspective of a woman at a bar listening to Thompson’s original on the jukebox, who then bristles at its sentiments and contends she’s in a road house not because she wants to be, but because her cheating husband has compelled her to be. When Thompson’s sanctimoniously sings, “I didn’t know God man honky-tonk angels,” Wells throws it right back at him and warbles, “It wasn’t God who made honky tonk angels,” before adding, “Too many times married men think they're still single. And that's caused many a good girl to go wrong.” Wells’ in-your-face rebuttal, along with the simple but unapologetic way she delivered it, struck a chord with people, but especially women, who suddenly found themselves – and in many cases their home lives – represented as never before on the radio. “It Wasn't God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels” began selling as few country singles had ever sold. But not without controversy. It eventually got banned on radio stations throughout the country, as well  as on NBC and the Grand Ole Opry. But not before Kitty Wells changed the course of musical history forever, and not before she became the first of her kind; a female country superstar who showed the world she was willing to go toe-to-toe with a man, and one who refused to blink in the process. She would eventually become the first female country singer to release a full length album, would eventually gain entry into the Country Music Hall of Fame, and would eventually become only the third country artist, behind Hank Williams and Roy Acuff, to receive the Grammy’s Lifetime Achievement Award. But Kitty Wills makes this list because she earned her title the “Queen of Country Music” the old fashioned way. Years ago and in a world that now seems so distant and so far removed, the young, soft-spoken and unassuming singer dared to walk alone down a dark and uncharted trail. And in the process, she was able to tear down a wall of sexual bias that had divided her world,

as on NBC and the Grand Ole Opry. But not before Kitty Wells changed the course of musical history forever, and not before she became the first of her kind; a female country superstar who showed the world she was willing to go toe-to-toe with a man, and one who refused to blink in the process. She would eventually become the first female country singer to release a full length album, would eventually gain entry into the Country Music Hall of Fame, and would eventually become only the third country artist, behind Hank Williams and Roy Acuff, to receive the Grammy’s Lifetime Achievement Award. But Kitty Wills makes this list because she earned her title the “Queen of Country Music” the old fashioned way. Years ago and in a world that now seems so distant and so far removed, the young, soft-spoken and unassuming singer dared to walk alone down a dark and uncharted trail. And in the process, she was able to tear down a wall of sexual bias that had divided her world,  her industry, and just maybe her country, for generations. And because she did that, and because she did it in such a quiet, polite and disarming manner, she made it much more likely that all those who would eventually walk in her footsteps – strong, independent types like Patsy Cline, Loretta Lynn and Tammy Wynette; Reba McEntire, Shania Twain and Taylor Swift – would someday find themselves in a position to not only explore their enormous talents, but actually realize them.

her industry, and just maybe her country, for generations. And because she did that, and because she did it in such a quiet, polite and disarming manner, she made it much more likely that all those who would eventually walk in her footsteps – strong, independent types like Patsy Cline, Loretta Lynn and Tammy Wynette; Reba McEntire, Shania Twain and Taylor Swift – would someday find themselves in a position to not only explore their enormous talents, but actually realize them.