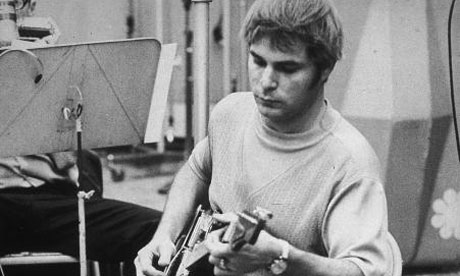

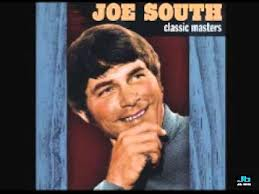

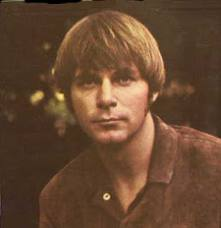

Of all the icons of 20th Century Americana, few offered such a rare blend of allure and intrigue as the young man with a guitar. And for anyone during the early to mid-1950's who saw a handsome kid named Joe South walking the streets of Atlanta, guitar in hand, what they saw was the very embodiment of what by then had become the newest, most unlikely incarnation of the American Dream – the hard-strumming, occasionally snarling, singer/songwriter.

Of all the icons of 20th Century Americana, few offered such a rare blend of allure and intrigue as the young man with a guitar. And for anyone during the early to mid-1950's who saw a handsome kid named Joe South walking the streets of Atlanta, guitar in hand, what they saw was the very embodiment of what by then had become the newest, most unlikely incarnation of the American Dream – the hard-strumming, occasionally snarling, singer/songwriter.

But unlike so many other kids with rock ‘n roll visions in their heads, for whom the guitar was merely a prop, or maybe something they’d use for a while and cast aside in time, Joe South and his guitar would always be one and the same. And wherever he went during those days and the ones that followed, that guitar of his would always be there by his side.

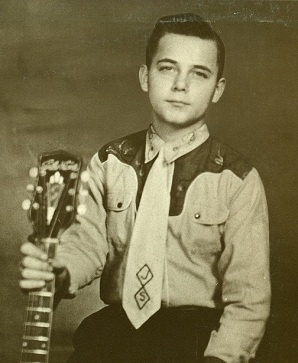

Joe South, you see, wasn’t just any kid with a guitar. He was a dynamo; a hurricane strapped to a six-string. Got one at age 11 from his daddy and taught himself to play the shit out of the thing. Tear it up, in fact. Play it like few people had ever heard a guitar get played before, and play it in a way that was unique to him.

Joe South, you see, wasn’t just any kid with a guitar. He was a dynamo; a hurricane strapped to a six-string. Got one at age 11 from his daddy and taught himself to play the shit out of the thing. Tear it up, in fact. Play it like few people had ever heard a guitar get played before, and play it in a way that was unique to him.

Joe South’s playing was not all Nashville-pure and yes ma’am-polite. It was not the least bit twangy or mournful, nor was it respectful of others or mindful. His guitar was rough, and angry, and maybe even a little mean.

It was a brand of guitar that defied you not to stand up and take notice; in fact, dared you not to.

And on top of all that, the kid turned out to be a tinkerer with a near pathological desire to experiment. That’s why one day he decided to completely re-wire his new electric guitar and modify its pickups.

And on top of all that, the kid turned out to be a tinkerer with a near pathological desire to experiment. That’s why one day he decided to completely re-wire his new electric guitar and modify its pickups.

That’s why as a high schooler he built his own radio transmitter from scratch, constructed a tower and launched his own radio station, which he ran out of his house, despite it being able to transmit no more than a mile or so.

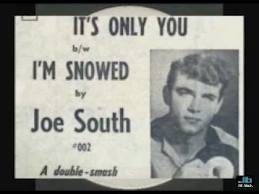

But it was that radio station and Joe South’s bold, distinctive guitar that first got him noticed; first earned him a spot on a weekend radio show playing for farmers and crack-of-dawn types on WGST in Atlanta. And it was those things that eventually got Joe a job as a staff guitarist for Bill Lowery’s National Recording Corporation; made him realize he wanted to write songs for a living, which he did for Lowery, composing a novelty hit for himself (The Flying Purple People Eater Meets the Witch Doctor), two tunes for rockabilly legend Gene Vincent (Gone, Gone, Gone and I Might Have Known) and a slightly uptempo number for local doo-wop group, The Tams (Untie Me), when they in turn took to #1 on the Soul charts.

As Lowery, who gave South that on-air job as a 12-year old, would later say: “I admired his courage so much that I put him on the air every Saturday at 6 a.m. He’d just come in every week with his guitar, stand in front of the microphone and start singing. Once in a while, he’d bring in a little song he’d written and I began to realize there was something special about this boy.”

As Lowery, who gave South that on-air job as a 12-year old, would later say: “I admired his courage so much that I put him on the air every Saturday at 6 a.m. He’d just come in every week with his guitar, stand in front of the microphone and start singing. Once in a while, he’d bring in a little song he’d written and I began to realize there was something special about this boy.”

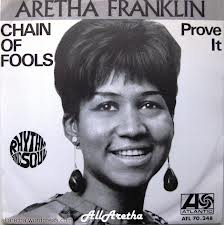

In a few years Joe outgrew NRC and Atlanta, and before his 20th birthday moved to Nashville to become a sideman. Soon he was playing on records by some of the biggest stars of the day, and was actually earning a living doing it. But again, Joe’s playing was just not suited to country, especially the pure-as-honey Owen Bradley stuff that ruled the early 60’s. So before long he found himself being flown to places like New York, Memphis and Muscle Shoals, to play behind rock, pop and soul artists like Wilson Pickett, Bob Dylan (Blonde on Blonde), Tommy Roe (Sheila), Simon & Garfunkel (Sounds of Silence) and, in particular, Aretha Franklin.

And it was Aretha’s 1967 hit Chain of Fools that allowed millions (including yours truly) to really hear Joe South for the very first time. Oh, we may not have known what we were hearing was him, especially at the time, but we heard him alright. We most definitely heard him.

And it was Aretha’s 1967 hit Chain of Fools that allowed millions (including yours truly) to really hear Joe South for the very first time. Oh, we may not have known what we were hearing was him, especially at the time, but we heard him alright. We most definitely heard him.

Because on the very first few seconds of Chain of Fools we got to hear Joe’s home-brewed electric; a brief but full-bodied slab of naked guitar teeming with so much attitude that in one sense seemed oddly disconnected from the rest of the song, but in another seemed absolutely pivotal to everything that was about to unfold.

Listen to the first four seconds of Chain of Fools -- that's all, just four seconds -- and notice how South strums and picks his intro before Aretha and her sisters take over. Listen to his guitar slowly uncoiling in a way that manages to be both understated and menacing at the same time.

But then, out of the blue, he stops dead and lets everything hang there. It’s as though the brash kid from Atlanta is saying through that guitar of his, “Hush y’all, and show some respect. This here’s the Queen of Soul.”

Because in Chain of Fools, Joe South’s guitar -- and not just at the beginning, but throughout -- is more than just a simple collection of notes. And it is more than just a guitar with a vague sense of purpose, or one playing by someone else's set of rules. It’s a guitar with muscle. It’s a guitar that carries with it a sort of musky, day-old aroma.

Because in Chain of Fools, Joe South’s guitar -- and not just at the beginning, but throughout -- is more than just a simple collection of notes. And it is more than just a guitar with a vague sense of purpose, or one playing by someone else's set of rules. It’s a guitar with muscle. It’s a guitar that carries with it a sort of musky, day-old aroma.

It is two and a half minutes worth of six-string tremolo with sweat on its brow, dirt under its fingernails, and hair on its shoulders. And for my money, it is a guitar part as brawny, as cocksure, and as proudly masculine as any ever recorded, including just about anything Duane Allman, Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page ever laid down.

I first came to Joe South through Birds of a Feather. It was 1968. Heard the song once, jumped on my Huffy and drove straight down to Gerber’s Music Store to buy it. Bam. Just like that.

Then, that very same day, just like Joe South, I went home and played the hell out of it. Played that new 45 again and again and again, and each time I played I found myself more and more lured in by the low, driving guitar hook that trumpeted the beginning of each verse – not to mention, of course, the man-sized voice of the guy at the mic. Talk about a young man and his guitar. Birds of a Feather was all that and a bag of nickels – at least, that is, to a freshly minted teenager in the summer of 1968.

Look, I’ll admit it may not be a great song. It never came close to being anything more than a regional hit. But I’ll be damned it isn’t a great recording. Because it’s real. And it’s honest. And I could tell, even as a 13-year old, that it came from a place deep within the soul of the man.

Look, I’ll admit it may not be a great song. It never came close to being anything more than a regional hit. But I’ll be damned it isn’t a great recording. Because it’s real. And it’s honest. And I could tell, even as a 13-year old, that it came from a place deep within the soul of the man.

You see, that was the thing about Joe South. In his hands, a Joe South song always had depth and texture. Because in his hands, a Joe South song always seemed to ring truer than it did in the hands of others.

Take I Never Promised You a Rose Garden. Sure it was a country smash for Lynn Anderson. And without question, it was a great recording of a terrific song. But when Anderson croons the money line, one might find it easy to get caught up in the melody, or maybe the unique way the song marries “pardon” with “garden.”

But when South sings the iconic phrase he himself wrote, “I beg your pardon; I never promised you a rose garden,” you can’t help but see the cold, steely resolve in the young man’s eyes or hear his unflinching relationship with the truth. It’s as though he’s telling his new bride in the only way he can, “Yeah, I know it ain’t much, but I never said it would be.”

But when South sings the iconic phrase he himself wrote, “I beg your pardon; I never promised you a rose garden,” you can’t help but see the cold, steely resolve in the young man’s eyes or hear his unflinching relationship with the truth. It’s as though he’s telling his new bride in the only way he can, “Yeah, I know it ain’t much, but I never said it would be.”

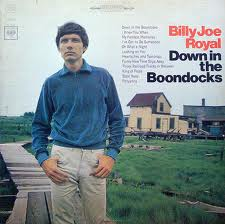

Same thing with Down in the Boondocks. In the hands of Billy Joe Royal, who turned the song into a Top Ten hit, it sounds a little like Pat Boone trying his best to do Little Richard, but entirely missing the point despite all the fun.

However when Joe South sings the line, “But I don’t dare knock upon her door ‘cause he daddy is my boss man,” it suddenly sounds almost like a tribute to Faulkner or Flannery O'Connor, all Southern, teeming with young hormones, and dripping with some dewy combination of sweat and Spanish moss.

When Joe South belts out his version of Down in the Boondocks you know immediately not only who the young man from the wrong side of the tracks is, but where he is. Hell, you can almost feel the Georgia sun baking the red clay, see the heat rising off the blacktop, and hear the cicadas in the trees.

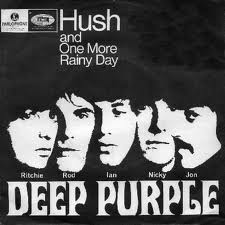

But for my money, the most poignant example of the difference between Joe South and someone doing Joe South is the 1968 hit, Hush. When Rod Evans of Deep Purple sings the title word, it sounds for all the world like space filler; a random, meaningless syllable sung merely to achieve a musical end.

But for my money, the most poignant example of the difference between Joe South and someone doing Joe South is the 1968 hit, Hush. When Rod Evans of Deep Purple sings the title word, it sounds for all the world like space filler; a random, meaningless syllable sung merely to achieve a musical end.

But in Joe South’s hands, the word hush is a command. It’s an order. And not a gentle one at that – given his ragged, angry guitar. In Joe South’s version, the guy lusts for his girl and he’s demanding that those around him shut up because he thinks – check that; he needs to believe – he hears her in the distance.

Don’t get me wrong. By Deep Purple, Hush is a great song, in large measure because of Jon Lord’s organ. But it’s a completely different song with a completely different meaning when performed by five Brits, than it is when played and sung with lustful, burning desire – the way Joe South does it.

Don’t believe me? Listen for yourself. (And do yourself a favor; crank it up,)

I’m not sure what happened to Joe South. For a while it all seemed to be working for him. For a three year stretch from the late 60’s to the early 70’s he seemed to be everywhere, winning a Grammy for Best Song, writing, singing and/or producing huge hits like Games, People Play, Walk a Mile in My Shoes, Don’t It Make You Wanna Go Home and (I Beg Your Pardon) I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, and becoming very much a regular on the primetime variety show circuit.

I even remember once reading a Playboy interview with the legendary agent Allen Klein, who at the time managed both the Stones and the Beatles, along with South. And in that interview he stunned me by contending that the single most talented member of his stable of musicians was not Mick Jagger, Keith Richard, Paul McCartney or even John Lennon. It was Joe South.

I even remember once reading a Playboy interview with the legendary agent Allen Klein, who at the time managed both the Stones and the Beatles, along with South. And in that interview he stunned me by contending that the single most talented member of his stable of musicians was not Mick Jagger, Keith Richard, Paul McCartney or even John Lennon. It was Joe South.

But then, just as quickly as it came – poof – it all seemed to disappear.

The company line is that the 1971 suicide of South’s brother, Tom, a member of his band, compelled him to abruptly retreat from the public eye. But the sudden and woefully unexplained demise of Joe South’s brilliant talent and career seems, even now, way more complicated than the mere death of a sibling – however unexpected and however traumatic.

As the decade wore on, rumors began swirling about steady drug use on South’s part, including heroin. Joe South’s behavior, which apparently could be prickly even in the best of times, according to a few reports got even more erratic as the decade progressed. Soon stories started to arise about him yelling things like “Kiss my ass” to audience members during what eventually slowly became smaller and smaller concert events.

As the decade wore on, rumors began swirling about steady drug use on South’s part, including heroin. Joe South’s behavior, which apparently could be prickly even in the best of times, according to a few reports got even more erratic as the decade progressed. Soon stories started to arise about him yelling things like “Kiss my ass” to audience members during what eventually slowly became smaller and smaller concert events.

He even dared to write and record a song around that time he titled simply, “I’m a Star.”

After the death of his brother, Joe South went on to release just one more album his entire life, in 1975, but it went nowhere and, in the opinion of many critics, deserved to go there.

There remains a school of thought that contends that drugs had always been at the root of Joe South’s behavioral and creative problems, as opposed to his brother’s suicide. In fact, some accounts hold that his brother’s suicide was itself a product of drug abuse.

South was later arrested on drug charges of his own and eventually moved to Hawaii, where according to the AMG Music Guide he lived a couple of years in the jungles of Maui.

Rumors, which may or may not have been based in truth, continued to follow the reclusive South over the course of the next few decades. One of the juicier ones even held that, burned out and no longer able to function, much less write or perform in front of an audience, he moved back into his mother’s home in Atlanta, where he lived for years,

I honestly don’t know what was true about Joe South and what wasn’t. Very little was written about him for the past four decades. All I know is that for a very short stretch during my teenage years he was like a comet in the night, hurling across the darkness and leaving a tail as brilliant as anything I’d ever seen.

And then, like I said – poof – it was gone. Or at least he was gone.

You can talk all you want about the deaths of rock legends like Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, Syd Barrett, Amy Winehouse and even John Belushi; terrific, and perhaps even brilliant young talents who fell victim to drugs and alcohol long before their time.

You can talk all you want about the deaths of rock legends like Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, Syd Barrett, Amy Winehouse and even John Belushi; terrific, and perhaps even brilliant young talents who fell victim to drugs and alcohol long before their time.

But let me tell you, Joe South may have been the biggest victim of them all. Because unlike all those others who actually died, at least physically, and who are now revered as some combination of hero and martyr; cultural icons for future generations to lionize and even idolize, Joe South wasn’t so lucky.

He lived.

Or that is to say, his body lived. Because, based on a wealth of evidence, his mind died, his muse died, and without question, something inside his soul died.

I don’t know this for a fact, of course, since I never talked to him or anyone who knew him. But my sense is, while Joe South’s heart may have been pounding away all these years, whatever it was in his soul that drove him as a boy to practice for hours on end, compelled him to write songs night after night, build a radio station, and get up before the crack of dawn each Saturday to play on the radio while other kids his age were tucked away in bed, that part of him died long before his body did.

As a result, for all the mistakes he made in life, Joe South ended up making the biggest mistake of all for someone in his chosen line of work. He simply faded away.

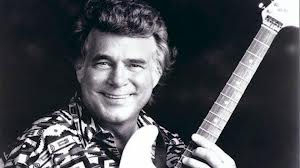

I’ll remember Joe South not so much for his hits, but his gifts. I’ll remember him for the rich, full-bodied timbre of his voice. I’ll remember the incredibly muscular nature of his guitar. I’ll even remember his ability to seamlessly marry gospel and rock, something very few artists have ever been able to – at least to the extent he did.

I’ll remember Joe South not so much for his hits, but his gifts. I’ll remember him for the rich, full-bodied timbre of his voice. I’ll remember the incredibly muscular nature of his guitar. I’ll even remember his ability to seamlessly marry gospel and rock, something very few artists have ever been able to – at least to the extent he did.

But perhaps most of all I’ll remember the uniquely Southern nature of his songwriting. Because above all, Joe South was a poet. The meter of his lyrics were matched only by their astounding visual power. In a single phrase, or in a simple lyric, he had the ability to take the mundane or the everyday and suddenly impart to you some deep, universal truth.

Even though I lived in the South for a time, I felt I knew a lot about the place even before I set foot there. A big part of that, of course, was having fallen in love with films like Cool Hand Luke, In the Heat of the Night and To Kill a Mockingbird. But a big part of it too was the music of Joe South. In one sense his songs were every bit as beautifully lyrical as those three classic movies, and every as Southern, if not more so.

That’s why I’d like to think Joe eventually retreated back to Atlanta, back the place it all started, to live out his days. Because for all his success and all his achievement in the music industry, he never seemed entirely comfortable as a rock star. In fact, in many ways he never seemed to be anything more than a grown up version of that good looking young kid who spent hours wandering the streets of his hometown, his guitar at his side.

That’s why when I heard he passed this week at the age of 72, I stopped what I was doing, put on a song of his I’ve grown to love over the years, and sat there quietly as it played.

That’s why when I heard he passed this week at the age of 72, I stopped what I was doing, put on a song of his I’ve grown to love over the years, and sat there quietly as it played.

And as I sat there and listened, it occurred to me I should share the song with you today, especially its last two verses and chorus. The song was never a huge hit for him, but it ended up being one of its best.

And what’s more, its chorus is one for the ages; one that repeats like a good old gospel standard, again and again, louder and louder, with hand-clapping and at a full octave higher, until at some point you find yourself being carried away and eventually, somewhere deep inside, you feel the rapture.

That feeling? That spirit? That rapture? For those who truly got him, that’s who Joe South was, and what his music was all about.

That, of course, and those first four seconds of Chain of Fools.

That, of course, and those first four seconds of Chain of Fools.

Thank you for the incredible passion, Joe. And for the music too. I know it was hard. And know it’s been a long time coming. But apparently God was willing and the creek didn't rise. Because it seems, child, you finally made it home.

But there's a six lane highway down by the creek

Where I went skinny dippin' as a child.

And a drive-in show where the meadow used to grow

And the strawberries used to grow wild.

There's a drag strip down by the riverside

Where my grandma's cow used to graze.

Now the grass don't grow and the river don't flow

Like it did in my childhood days.

Don't it make you wanna go home, now?

Don’t it make you wanna go home?

All God’s children get weary when they roam.

Don’t it make you wanna go home?