Nat Allbright

Nat Allbright

For roughly a decade, starting in 1951, had one of the most interesting and thankless jobs in baseball. Allbright used to use – get this – teletype reports in Morse Code, sound effects and a truly remarkable descriptive ability to re-create and broadcast Brooklyn (and for a brief time, Los Angeles) Dodger games for a network of dozens of radio stations up and down the east coast. In his day, he would attend only Dodger spring training games, where he would memorize each player’s stance, habits and peculiarities on the field and then subsequently integrate them into his broadcasts – something he did over 1,500 times in his career.

Matty Alou

Matty Alou

One of the three Alou brothers who, on September 15, 1963 in Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, while playing for the San Francisco Giants, once lined up alongside one another in the same OF. The Giants starters that day were Felipe Alou in RF, Willie Mays in CF and Willie McCovey in LF. But in the 7th inning and the Giants up 8-2, Jesus Alou replaced McCovey and went to RF, with Felipe moving over to LF. Then in the bottom of the 8th, after the Giants had tacked on four more, Matty was sent in the game to play LF, with Felipe moving to his third position of the day, CF. It was the first time three brothers had ever played in the same outfield at the same time before, one of whom played all three OF positions in the same inning.

Alou was then dealt to the Pirates following the 1965 season, and at the time was a .260 hitter with warning-track power. Batting leadoff for the Bucs under legendary hitting guru Harry “the Hat” Walker, who convinced Alou that all he had to do was shorten his swing, use a bigger bat, slap the ball the other way, and run like hell, Alou proceeded to slap-hit his way – in an utterly pitching-dominant era, mind you – to not only a league batting title in '66, but successive batting averages of .342, .338, .332 and .331.

Alou was then dealt to the Pirates following the 1965 season, and at the time was a .260 hitter with warning-track power. Batting leadoff for the Bucs under legendary hitting guru Harry “the Hat” Walker, who convinced Alou that all he had to do was shorten his swing, use a bigger bat, slap the ball the other way, and run like hell, Alou proceeded to slap-hit his way – in an utterly pitching-dominant era, mind you – to not only a league batting title in '66, but successive batting averages of .342, .338, .332 and .331.

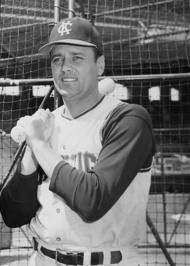

Gino Cimoli

Gino Cimoli

A fringy, fourth OF-type in the late Fifties and early Sixties. Cimoli signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers after graduating from San Francisco’s Galileo High, where both Joe DiMaggio and O.J. Simpson went. A few years later, when he led off for the Los Angeles Dodgers in the San Francisco Giants’ home opener in April of 1959, he became the first man to bat in a Major League game played on the west coast.

A few months later, after being dealt to the Pirates, he found himself a platoon CF along with Bill Virdon on the Bucs' '60 World Championship team. In fact, Cimoli was on base with a leadoff single when Dick Groat hit his infamous 8th inning double-play grounder that took a bad hop, struck Tony Kubek in the throat, and breathed life into what would become a critical, five-run rally.

When he retired, Cimoli left baseball and became a local driver for United Parcel Service. In 1990, he was given an award for working his delivery route for 21 years without an accident, and was known right up to the day he died as “the Lou Gehrig of UPS.”

When he retired, Cimoli left baseball and became a local driver for United Parcel Service. In 1990, he was given an award for working his delivery route for 21 years without an accident, and was known right up to the day he died as “the Lou Gehrig of UPS.”

Wes Covington

Baseball historians will remember Bob “Hurricane” Hazle as a rookie who came up late in the season, played like a demon, and helped the power-hitting Milwaukee Braves win their first and only World Championship in 1957. But another minor league call-up from the Braves’ farm club in Wichita that season, Covington, might have been even more important to the team’s fate.

Covington, who started the season in AAA, played only 96 games for Milwaukee that year, the bulk of them after the All Star game. But in those 96 games, Covington batted .284 with 21 HR and 65 RBI. Oddly, even though he only hit four doubles for the Braves that season, he somehow managed to hit eight triples.

Covington, who started the season in AAA, played only 96 games for Milwaukee that year, the bulk of them after the All Star game. But in those 96 games, Covington batted .284 with 21 HR and 65 RBI. Oddly, even though he only hit four doubles for the Braves that season, he somehow managed to hit eight triples.

Following the season and during the World Series, it was Covington who was as responsible as any Braves position player for the team's Series win and for Lew Burdette's taking home the Series’ MVP award. In Game Two, with the Braves down 1-0 in games and Burdette on the mound, Covington took what looked like a sure extra-base hit away from Bobby Shantz with a diving catch to help secure a 4-2 road win over the Yankees. Then in Game Five, with the series tied 2-2 and Burdette once again on the mound, he robbed Gil MacDougal of a sure home run to help preserve a 1-0 win over Whitey Ford.

Covington never regained the magic of that ’57 season and was traded a few times over the next decade before finally deciding to call it quits after the 1966 campaign, during which he pinch-hit and did spot duty for the pennant-winning Dodgers.

Covington never regained the magic of that ’57 season and was traded a few times over the next decade before finally deciding to call it quits after the 1966 campaign, during which he pinch-hit and did spot duty for the pennant-winning Dodgers.

Covington, a native North Carolinian, then placed baseball in his rear view mirror, moved to – of all places – Alberta, Canada, and worked for many years as the ad manager of the Edmonton Sun, before succumbing to cancer this past Fourth of July.

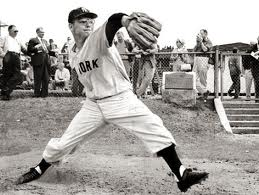

Ryne Duren

Ryne Duren

Another one of those former Kansas City A’s offered up as evidence that for years the hapless A’s were little more than a farm club for the powerful New York Yankees, in large part because Kansas City seemed to regularly trade young, talented, future All Stars like Duren and Roger Maris to the Bombers for players whose best days were behind them.

Duren was a monster of a man with a tremendous affinity for both late-game showmanship and adult beverages. He wore thick, coke-bottle glasses, was among the most intimidating, hardest throwers of his day and would slowly stroll menacingly toward the mound when summoned from the bullpen.

He was also a guy whose control was either strategically bad or, just maybe bad by nature. Whatever the case, few batters ever dared to dig in against him for fear it might be the last thing they ever did. Or, as Casey Stengel once said about his three-time All Star, "I would not admire hitting against Ryne Duren, because if he ever hit you in the head you might be in the past tense."

He was also a guy whose control was either strategically bad or, just maybe bad by nature. Whatever the case, few batters ever dared to dig in against him for fear it might be the last thing they ever did. Or, as Casey Stengel once said about his three-time All Star, "I would not admire hitting against Ryne Duren, because if he ever hit you in the head you might be in the past tense."

Ironically, Derwent Sandberg was such a big fan of the fireballing, showboating (and occasionally headhunting) Yankee reliever that in 1959 the Spokane, Washtington mortician named the youngest of his four kids after him. That kid, a son, would eventually grow up to play a pretty nice little 2B for the Chicago Cubs.

Mike Flanagan

Mike Flanagan

A two-time All Star and one-time Cy Young Award winner for the Baltimore Orioles, who would go on to serve in four different capacities for the club; player, coach, general manager and color commentator. Flanagan was a relatively soft-throwing but pinpoint-precise lefty – a pitching style he adopted working alongside Oriole teammate Scott McGregor – whose wit was often as sharp and as deadly as his breaking ball.

People mistakenly give ESPN’s Chris Berman credit for starting the silly nickname craze in baseball, making amusing and sometimes cringe-worthy puns out of different players’ names (Bert “Be Home” Blyleven). But years before ESPN even went on the air, Peter Gammons, in his ground-breaking and widely read weekly “Sunday Baseball Notes” column in the Boston Globe, regularly featured Flanagan’s best nicknames for players around the American League.

For Flanagan, the Twins’ John Castino was John “Clams” Castino, while the Brewers Sixto Lezcano became “Mordecai Six Toe” Lezcano. In 1980, Flanagan once called the four members of that year's O’s rotation, "Cy Young" (himself), “Cy Old” (Jim Palmer), “Cy Present” (Steve Stone), and “Cy Future” (McGregor).

Berman, of course, was a sports announcer for a television station just outside of Boston at the time Gammons was featuring Flanagan’s nicknames.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts, part of Flanagan's deal when signing with the Orioles was that they would pay for the final years of his college education, which they did. At UMass, Flanagan not only played baseball, but was on the freshman basketball team as well, where he scrimmaged regularly against NBA legend, Julius Erving, who also went to the Amherst school.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts, part of Flanagan's deal when signing with the Orioles was that they would pay for the final years of his college education, which they did. At UMass, Flanagan not only played baseball, but was on the freshman basketball team as well, where he scrimmaged regularly against NBA legend, Julius Erving, who also went to the Amherst school.

Flanagan’s best season as an Oriole came in 1979, when he went 23-9 and fashioned a 3.09 ERA, while leading Baltimore into the World Series. For his efforts, he earned that year's A.L. Cy Young Award.

This past summer, apparently despondent over some significant financial problems and reeling from what he viewed as a failed tenure in the Oriole front office, he went into the woods behind his house in Maryland, put a shotgun to his head, and pulled the trigger. Flanagan was 59. At the time of his death he was still working as an analyst for Oriole games on the Mid-Atlantic Sports Network (MASN), opposite Gary Thorne.

Bob Forsch

Bob Forsch

A much better all-around player than many fans realize. He’s still #3 on the all-time St. Louis Cardinal list for victories. He’s the only Cardinal hurler to throw two no-hitters. He and brother, Ken Forsch, are the only brothers in Major League history to each twirl no-hitters. He also played on two pennant-winners, earned a World Series ring in 1982, and won 20 games in 1977.

A converted minor league 3B, he remained a great hitting pitcher throughout his career, homering twelve times at the big league level, hitting .300 in 1975, winning the first-ever Silver Slugger Award for pitchers in 1980, and taking home the award again in 1987.

Joe Frazier

Joe Frazier

A great baseball man who was truly at the wrong place at the wrong time. As a loyal organizational soldier, he managed in the New York Mets’ farm system in the late sixties and early seventies and won at multiple levels with an almost missionary-like dedication to fundamentals.

But by the time he was finally given the helm of his first big league club in 1976, New York’s once-respectable lineup was by then littered with fringy prospects and role players like Mike Vail, George Theodore and Benny Ayala. What’s more, the Mets’ pitching staff had begun to be built around back-of-the-rotation arms like Nino Espinosa, Pat Zachary and Craig Swan. Frazier subsequently helmed a woefully undermanned ’76 team to a remarkable 86-76 record and a third place finish.

But in 1977, when they started a more realistic 15-30, he was unceremoniously dumped by the Mets’ brass in favor of Joe Torre and was never given a big league shot again. His former team, meanwhile, proceeded to finish last or next-to-last the next seven straight seasons.

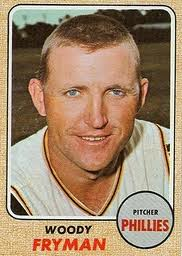

Woodie Fryman

Woodie Fryman

A physically unassuming southpaw who, through a combination of guts and guile, earned himself a few moments in the sun, not to mention a couple of All Star nods.

Fryman signed with the Pirates as a 25-year old in 1965, and the next year was immediately thrown into one of the most-heated pennant races in National League history. Initially a middle reliever, he soon found himself in the rotation and in one stretch helped keep the pitching-challenged Bucs close by shutting out the Phillies, Mets and Cubs in succession. In the second of those three shutouts, against New York, Ron Hunt led off with a single and was thrown out stealing. Fryman subsequently retired the next 26 batters.

A few years later, after having been traded to the Phillies in a multi-player deal that included Jim Bunning, he went 10-5 with a 1.61 ERA through June 18 and made the All Star team.

Then, in 1972, after having been sent in a mid-season trade to the Tigers, he found himself in yet another hotly contested pennant race. And again he rose to the occasion. Pitching in a new league, Fryman fashioned a 9-3 record with a shimmering 2.21 ERA for Detroit.

Then, in 1972, after having been sent in a mid-season trade to the Tigers, he found himself in yet another hotly contested pennant race. And again he rose to the occasion. Pitching in a new league, Fryman fashioned a 9-3 record with a shimmering 2.21 ERA for Detroit.

But one game in particular defined the season for the occasionally over-achieving journeyman. On the second last day of the year, facing the power-laden, second-place Red Sox who trailed Detroit by just ½ game, the southpaw battled Boston’s Luis Tiant pitch for pitch. Fryman gave up an unearned run in the first, but only two hits the rest of the way.

The Tigers, meanwhile, scratched across a run in the 6th and two in the 7th to win game and the division behind their soft-tossing, portly, but at remarkably critical times, tough-as-hell lefthander

Lou Gorman

Lou Gorman

An Irish Catholic kid from Providence who grew up a die-hard Red Sox fan, and who as GM helped build both the Sox’ ill-fated 1986 World Series club and their powerful but ultimately not-quite-good-enough teams of the Nineties, featuring the likes of Mo Vaughn, John Valentin,Wade Boggs and Mike Greenwell.

Gorman, who learned the game “the Oriole way” while working for Baltimore in the early Sixties, became the first-ever farm director of the expansion Kansas City Royals and helped turn KC into a model franchise that soon began fighting the Yankees tooth-and-nail for AL supremacy. He later became the first-ever GM of the expansion (and undercapitalized) Seattle Mariners. With his first pick of the expansion draft he selected Rupert Jones, and with his first amateur pick selected Alvin Davis, both of whom turned out to be very good big leaguers for the M’s.

Gorman also worked for a time as head of player personnel with the New York Mets and assisted one-time co-worker Frank Cashen, who had cut his teeth with Gorman in Baltimore, in re-building the then-hapless Met franchise through shrewd draft picks like Darryl Strawberry, Lenny Dykstra and Dwight Gooden and key trades for undervalued stars like Keith Hernandez.

Gorman also worked for a time as head of player personnel with the New York Mets and assisted one-time co-worker Frank Cashen, who had cut his teeth with Gorman in Baltimore, in re-building the then-hapless Met franchise through shrewd draft picks like Darryl Strawberry, Lenny Dykstra and Dwight Gooden and key trades for undervalued stars like Keith Hernandez.

Ironically, in 1986, the Mets that Gorman helped build went on to break hearts throughout New England when they stunningly came back to shock his Red Sox -- with Gorman as GM -- in that year’s now-classic World Series.

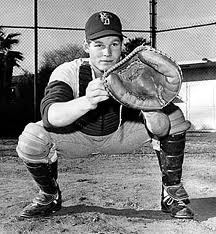

Greg Goossen

Greg Goossen

A catcher and sometime first baseman who was originally signed with the Dodgers, spent a number of years in the Mets system, and was traded prior to the 1969 season to the expansion Seattle Pilots. While the deal robbed him of his chance to earn a World Series ring with the Miracle Mets of ‘69, it did allow him to become a central character in Jim Bouton’s legendary and often unvarnished look at the ins and outs of a Major League clubhouse, Ball Four, which Bouton wrote about Seattle’s ’69 season.

Following his baseball days, Goossen briefly worked as a private investigator in a firm he started while still an active player. He then helped his brother train the 1980’s middleweight boxing champion, Michael Nunn. Around that same time Goossen also had a chance meeting with actor, Gene Hackman, and in short time the two became fast friends. Eventually, Hackman began insisting that Goossen be used as his stand-in during film shoots, before Goossen in turn started earning small roles for himself in a number of big-budget features, like Waterworld, Unforgiven, The Firm, Get Shorty, The Royal Tenenbaums and Wyatt Earp.

Following his baseball days, Goossen briefly worked as a private investigator in a firm he started while still an active player. He then helped his brother train the 1980’s middleweight boxing champion, Michael Nunn. Around that same time Goossen also had a chance meeting with actor, Gene Hackman, and in short time the two became fast friends. Eventually, Hackman began insisting that Goossen be used as his stand-in during film shoots, before Goossen in turn started earning small roles for himself in a number of big-budget features, like Waterworld, Unforgiven, The Firm, Get Shorty, The Royal Tenenbaums and Wyatt Earp.

Part Two of Three: more 2011 baseball deaths you may have missed.

Part Three of Three: more 2011 baseball deaths you may have missed.