I never knew Harmon Killebrew. But I knew Donnie Cieloch.

I never knew Harmon Killebrew. But I knew Donnie Cieloch.

And when I was a kid growing up in Syracuse, New York, in my neighborhood Don Cieloch was Harmon Killebrew.

Cieloch (pronounced SEE-lock) was a short, barrel-chested Polish kid who lived just down the street from me. And he wasn't so much a great athlete, as he was a great ballplayer. Donnie wasn't fast, for example, but he sure knew how to take an extra base on you whenever you gave him half a reason to do so.

And while he didn't have a tremendous amount of range in the field, he could catch just about everything he ever got his hands on, especially those tough one-hoppers in the dirt.

In fact, in the summer of 1967, when we would choose up sides for pickup games at Cherry Road School, Donnie was not only picked first, he usually played first. (Though, truth be told, he also played a pretty capable third base, when given the chance.)

But don't get me wrong. Donnie Cieloch didn't get picked first day after day that summer because he was a good baserunner and a decent fielder. Lord knows there were plenty of us in Westvale who could run outrun or out-field Donnie Cieloch.

But don't get me wrong. Donnie Cieloch didn't get picked first day after day that summer because he was a good baserunner and a decent fielder. Lord knows there were plenty of us in Westvale who could run outrun or out-field Donnie Cieloch.

And heaven forbid, we didn't pick him first because we were afraid not to.

Heck, Donnie Cieloch was one of the kindest, gentlest, and most good-natured guys we knew. Not to mention, one of the most humble and soft-spoken. Which was probably just as well, because as strong as he was -- and he truly was a fireplug in both strength and stature -- he could have swept the infield dirt with most of us, had he been so inclined.

No, Donnie Cieloch got picked first every time we played in the summer of 1967 because to the 12 and 13-year old versions of ourselves, he was the single greatest hitter in our little world.

What's more, to our young and still-wide eyes, he possessed the most fluid and powerful swing we had ever seen.

While the rest of us chose to incorporate a nearly incomprehensible collection of hitches, twitches and tics into our batting stances, and then add a dash or two of additional motion just as the pitch approached -- you know, just for good measure -- Donnie would do the exact opposite.

While the rest of us chose to incorporate a nearly incomprehensible collection of hitches, twitches and tics into our batting stances, and then add a dash or two of additional motion just as the pitch approached -- you know, just for good measure -- Donnie would do the exact opposite.

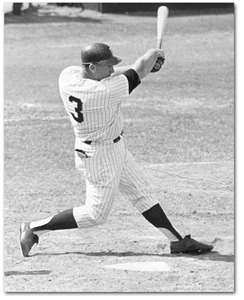

He would stand in the batter's box like a statue, dead still; his big bat cocked, his head steady, his shoulders slightly hunched and his feet squared dead-center to the pitcher, with both eyes peering out from behind a massive left bicep.

The only movement we would ever see would be a subtle, almost ominous twirling of his bat, all long and thick, and blackened with pine tar.

But at the moment of truth -- the very moment a good pitch came within swatting distance of Donnie Cieloch -- that was the moment he separated himself from every other kid in Westvale.

At that moment, Donnie's bat would twitch and then explode in the direction of the ball in a smooth, sweeping and slightly upward-bound arc. His left foot would move forward almost imperceptibly as his upper body and the cheeks on his round face would puff out, almost as if he were trying to move a brick by blowing it forward.

At the very moment of contact, both of Donnie's arms would extend straight out from his big barrel chest, with his elbows locked, making it seem, if only for an instant, that his bat and his thick, powerful arms were a single unit fused to (and extending from) a point just below his shoulders.

At the very moment of contact, both of Donnie's arms would extend straight out from his big barrel chest, with his elbows locked, making it seem, if only for an instant, that his bat and his thick, powerful arms were a single unit fused to (and extending from) a point just below his shoulders.

As he continued whipping the barrel of his bat through the hitting zone, Donnie would lean on his back leg and bend it ever-so-slightly, while extending his left leg straight out toward the pitcher, locking it tight and transforming his entire left side into something just a few years later I would learn was a hypotenuse -- the long sloping front side of a perfectly formed isosceles triangle.

Then as he started to drive through the ball, sending it back from where it came, and then some, you'd see Donnie's head lock on to a point near the end of his bat, his eyes scowling at the dirty baseball and his puffy cheeks blowing outward as he rolled his right hand over his left one, at the same time clearing his hips and pronating his now fully extended front foot until it teetered on the outer rim of his beat up old left sneaker.

And the sound.

My God, the sound!

Even four decades later there are few sounds I know that can send chills down my spine like the sound Donnie Cieloch's big wooden bat used to make when it caught a sandlot fastball just so.

Even four decades later there are few sounds I know that can send chills down my spine like the sound Donnie Cieloch's big wooden bat used to make when it caught a sandlot fastball just so.

It was a deep sound, a rich sound, a beautiful sound, and it echoed and continued echoing even as that ragged old baseball, with its dirty brown skin and fraying red stitches, arched skyward toward the left fielder, who by that time was usually playing so deep that, if we didn't already know who it was out there, we'd never be able to make out his face.

What's more, Donnie Cieloch was one of the handful of guys on the Cherry Road diamond that summer who hit a ball with backspin. And not just casual backspin, but vicious backspin, grown-up backspin; real honest-to-goodness traction-inducing and gravity-defying backspin.

The rest of us, when we got a hold of one, usually would hit it with enough topspin that the ball would invariably drive itself back into the ground, often in the gaps between the outfielders.

But the balls Donnie hit had such incredible backspin that when he'd crack one it would arc majestically outward, gaining altitude as it climbed its way though the hot, sticky air toward the stately pines that lined the outer perimeter of our home diamond.

Unlike me, whose hardest hit balls that summer always seemed to seek out an Earth-bound resting place, when Donnie Cieloch really got into one, it somehow seemed as though the ball would leave his bat seeking a path to heaven.

[pullquote]At that moment, Donnie’s bat would explode in the direction of the ball in a smooth, sweeping and slightly upward-bound arc. His left foot would move forward almost imperceptibly as his upper body and the cheeks on his round face would puff out, almost as if he were trying to move a brick by blowing it forward. [/pullquote]The summer of '67 was a magical time.

It was the Summer of Love.

It was the Summer of Sgt. Pepper's.

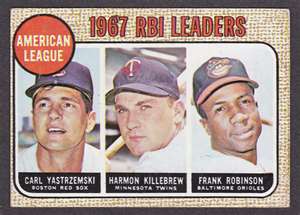

And to baseball fans across the country, it was the Summer of the Greatest Pennant Race Ever; a six-month marathon that would culminate with four American League teams -- the Twins, Tigers, Red Sox and White Sox -- all within a game of one another heading into the final week of the season.

What's more, back then, before the creation of a toxic consolation prize called the Wild Card, the stakes were so much higher. It was win or go home.

The summer of '67 was also the summer of Yaz's Triple Crown, the summer of Lonborg's Cy Young and the summer the perennially hapless Red Sox finally started living what some enterprising sportswriter called their "Impossible Dream."

The summer of '67 was also the summer of Yaz's Triple Crown, the summer of Lonborg's Cy Young and the summer the perennially hapless Red Sox finally started living what some enterprising sportswriter called their "Impossible Dream."

But in the summer of 1967, I was not a Red Sox fan.

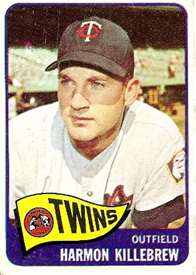

I was a Twins fan. Because I was a Harmon Killebrew fan.

And when the Twins' hopes died that final weekend in Fenway, as they lost two in a row to a truly inspired Boston team, a little part of me died with them.

I'll never forget watching the final two games on NBC, watching as Yaz completed the greatest season I'd ever seen a player have, watching him carry his team as no hitter had ever carried a team, watching him win the American League pennant virtually by himself.

It wasn't until years later that I looked up the numbers and realized it wasn't Yaz that beat the Twins that summer.

It was the Twins that beat the Twins. Or at the very least, it was their stubborn manager. But that's another story for another time.

This much was clear, however -- even then -- to anyone who watched the Twins and Sox in 1967, or pored over their box scores each morning as if looking for clues to a mystery: as great as Carl Yastrzemski was that year, Harmon Killebrew was right there with him.

But that's the way it always was with Killebrew. Always in someone else's shadow.

Even the year he got inducted into the Hall of Fame, who did he go in with?

Hank Aaron.

Maybe nice guys do finish second.

Harmon Killebrew died just over a week ago, the victim of esophageal cancer. And his passing was mourned, as it should have been, throughout Major League Baseball. But those hit hardest by his passing were the fans in Minnesota, those who knew Charmin' Harmon best.

I never knew Harmon Killebrew. But I knew Donnie Cieloch.

I never knew Harmon Killebrew. But I knew Donnie Cieloch.

And I was sad to learn he's now gone too. Don Cieloch died seven years ago of a heart attack in Buffalo, a divorced father of two who lived out his days making cars in the local GM plant.

But because I shared one special summer with both men, when I first learned of their passing what came to mind was not sadness, but a fading image: a grainy, black & white mental snapshot of the single most beautiful right-handed swing I'd ever seen.

A swing shared by two kind, gentle and remarkably humble men; two men separated by a thousand miles of highway, a couple decades' worth of summers, and a lifetime of fate.

A short, compact, powerful swing. A cleanup hitter's swing.

The kind of swing that once upon a time could send a ball skyward, full of backspin; almost as though it was seeking a path to heaven.