Remember in the 90's when tribute albums were all the rage? When different (and often diametrically opposed) artists would go into the studio and pay their musical respects to a specific icon, songwriter or theme by laying down a single track, which would then be combined with other such tracks by other such artists to form a unique, one-of-a-kind album?

When they worked (like If I Were a Carpenter, a quirky but refreshing homage to the pop hits of the Carpenters by edgy, critical darlings like Sonic Youth, The Cranberries and others) the results could be magic. More often, however, they ended up like so many other financially motivated studio concoctions; one or two gems followed by a parade of near-misses and flat-out misfires.

One of the most daring (and to some degree, successful) such albums was Rhythm County and Blues, which brought contemporary country and R&B stars together to sing duets on eleven gems from the two genres. Conceived by Tony Brown, produced by Don Was, and featuring some top-of-the-line sidemen, the album was built on a simple, but rock-solid premise: that traditional country and R&B share the same musical DNA and are, therefore, a lot more alike than many fans of either would care to admit.

The disc's eclectic mix of singers and songs was probably more compelling on paper than it ended up being in the studio, but it was tough not to be intrigued by the track listing:

1. "Ain't Nothing Like the Real Thing" — Vince Gill with Gladys Knight

(Written By Valerie Simpson & Nickolas Ashford)

2. "Funny How Time Slips Away" — Al Green with Lyle Lovett

(Written by Willie Nelson)

3. "I Fall to Pieces" — Aaron Neville with Trisha Yearwood

(Written by Hank Cochran & Harlan Howard)

4. "Somethin' Else" — Little Richard with Tanya Tucker

(Written by Eddie Cochran & Sharon Sheeley)

5. "When Something Is Wrong with My Baby" — Patti LaBelle with Travis Tritt

(Written by Isaac Hayes & David Porter)

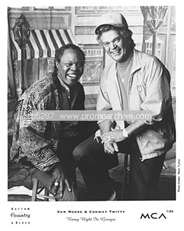

6. "Rainy Night in Georgia" — Sam Moore with Conway Twitty

(Written by Tony Joe White)

7. "Chain of Fools" — Clint Black with The Pointer Sisters

(Written by Don Covay)

8. "Since I Fell for You" — Natalie Cole with Reba McEntire

(Written by Buddy Johnson)

9. "Southern Nights" — Chet Atkins with Allen Toussaint

(Written by Allen Toussaint)

10. "The Weight" — The Staple Singers with Marty Stuart

(Written by Robbie Robertson)

11. "Patches" — George Jones with B. B. King

(Written by Ronald Dunbar & General Johnson)

I'll spare you a synopsis of each track (a couple of were pretty bad) and focus instead on a song that turned out to be one of the most soulful, spirited and (for me) deeply moving musical moments of the decade: Sam Moore and Conway Twitty's cover of Brook Benton's ”Rainy Night in Georgia."

For those who don't know, Moore was the "Sam" half of the old Stax-based soul duo, Sam and Dave ("Soul Man," "Hold On, I'm Comin'"). A daring, expressive tenor, Moore could often sound like a soaring, wailing lead guitar to his partner Dave Porter's gritty, full-bottomed bass of a voice.

Twitty, meanwhile, was a former pop star who crossed over and became one of the seminal country voices of his generation. Like Moore, Twitty also frequently went into the studio with a partner (he and Loretta Lynn recorded many songs together, including five straight #1 hits), so when the two stars agreed to lay down Tony Joe White's 1968 classic, each was well versed in the often-fickle dynamics of duet singing.

Their version starts off innocently enough, with Twitty flying solo on the first verse. At this point "Rainy Night" feels like a well-meaning but largely lukewarm imitation of the Benton original, with the singer -- sad, lonely and hovering by his suitcase -- trying desperately to outrun the pain of some lost love.

But then Moore takes over in the second verse and does something that fundamentally changes the song. His voice is unfettered and lilting. And with each word he sings and each musical phrase he weaves, "Rainy Night" becomes less dark. In Moore's hands the tune is still sad and plaintive, but now there's a real sense of hope, almost as though the singer has found an inner resolve and can imagine a day when, like so many other things he's loved and lost, he'll be able to look back on this woman and find comfort in her memory.

[pullquote]In Moore's hands the tune is still sad and plaintive, but now there's a real sense of hope, almost as though the singer has found an inner resolve and can imagine a day when he'll be able to look back on this woman and find comfort in her memory. [/pullquote]But Moore does something else as well. He establishes that his role will be complementary and that "Rainy Night" will remain Twitty's tale to tell. He'll serve simply as a musical counterbalance to his country cousin. It's as though the singer takes a half-step back and cedes center stage to Twitty. And when he does, Twitty reaches out and grabs the moment.

"How many times I wonder," he belts out in the song's bridge, " and it still comes out the same." Then Moore, like some jazz-inspired chorus, mitigates Twitty's melancholy with his hope-laden rendering of the next two lines, which he modifies ever-so-slightly from the original. "No matter how you look at it, or think of it," Moore sings, "you see...it's life and we've just got to play the game."

By shifting from the second person singular voice to the first person plural (changing the "you" in Benton's original to the collective "we") and adding the phrase "you see," he makes the line less dour and cynical than originally written, and uses it to gently remind us that pain is universal and that we are all in this thing together.

But make no mistake; despite Moore's spirited vocals, the song's overriding presence remains Twitty. He and his powerful, bluesy, and slightly ragged baritone are its anchor. And when this version of "Rainy Night" begins its long, protracted and beautiful fade, that fact becomes abundantly clear. Because the fade is the point at which this particular version finds a higher gear and becomes something more than just another cover of a 25-year old chestnut.

In fact, much like Elvis Presley's "Suspicious Minds," with its hypnotically repetitive, Gospel-flavored coda, in the case of Moore and Twitty's version of "Rainy Night in Georgia," the fade not only makes the song; it is the song.

It's important to note here who the two singers are; two men of roughly the same age, one black and one white; dirt-poor kids from the Jim Crow South who spent their boyhood days in two worlds divided by a wall of hatred and ignorance; men who years ago would have never had the chance to know one another, much less play with one another. Yet that's exactly what they're doing here. They're playing. And just like two kids in a sandlot, a tree house or some muddy old swimming hole, they couldn't be happier.

[pullquote]Much like Elvis Presley's "Suspicious Minds," in the case of Moore and Twitty's "Rainy Night in Georgia," the fade not only makes the song; it is the song[/pullquote]The song's fade is actually a 90-second, improvised call-and-response jam, with the two men playing off one another to intoxicating effect. At one point Twitty tells Moore the sound of falling rain reminds him of his old tin roof back home. Moore answers, "It does. It really does." It's at that moment that these two very different men from two very different worlds come together in a way that, truth be told, they hadn't until then; united in song and bound by memories of days gone by and the warm rainy nights that were so much a part of their childhood in the Deep South.

Moore at this point starts scatting, clearly carried away by the moment, and impishly coaxes Twitty to do the same. "C'mon, try, try, try," Moore urges his partner, who over the course of so many years crafted one of the most no-nonsense public personas in country music. It's to no avail, however, and Twitty simply replies, "I want to Sam, but I can't."

Moore then urges Twitty to give one of his signature low, sensual moans, which he does to his partner's delight. Moore returns the favor by offering up one of his own.

Now for more background: this version of "Rainy Night" was recorded in 1993, just months before Twitty would die unexpectedly. The song would not be released, however, until the spring of the following year. I first heard it when someone gave me "Rhythm Country and Blues" as a gift. So I not only heard this version for the very first time on my home stereo with the volume up, I did so with the abrupt nature of Twitty's passing still echoing down some deep dark corridor of my mind.

For that reason, when I heard him interject, amid all this playful banter, a rhetorical and heartfelt, but eerily faraway, "Awww Brook Benton, where are ya' son?" I literally got chills and felt a quiver of emotion well up inside me.

Benton, a black man like Moore, and a contemporary of Twitty's, had died just four years earlier. And as I listened I could hear an aging Twitty (who I sensed for one fleeting moment, felt all alone in that studio full of people) crying out to a departed friend and colleague. In a musical sense, he seemed to be saluting Benton for taking a simple ballad and turning it into a timeless classic. But in a deeper, far more personal one, it was as though Twitty was calling out to Benton, assuring him that, wherever he was and whatever he was doing, not to worry; his old buddy Conway would be joining him soon.

The song ends a few bars later, and does so in fitting fashion. Moore, who began "Rainy Night's" intoxicating fade with a brief bit of vocal improv that he punctuated by singing his duet partner's first and last names, ends it with a joyous and slightly giggled "Conway!" -- as though asking the engineers, producers and other musicians in the room to give it up for a guy one Nashville scribe once called "the best friend a song could ever have."

The song ends a few bars later, and does so in fitting fashion. Moore, who began "Rainy Night's" intoxicating fade with a brief bit of vocal improv that he punctuated by singing his duet partner's first and last names, ends it with a joyous and slightly giggled "Conway!" -- as though asking the engineers, producers and other musicians in the room to give it up for a guy one Nashville scribe once called "the best friend a song could ever have."

And believe me, when you hear this version for the first time you'll understand why. Because in the hands of Sam Moore and Conway Twitty, "Rainy Night in Georgia" becomes something more than just one more sad lament to lost love. It becomes a joyous testament to the power of music to tear down walls.

What's more, it emerges as proof positive that every once in a while two very different people, from two very different worlds, can find comfort in a single shared memory of a place far, far away and a time oh-so-long ago.