Among the many men and women who left us in 2018 from the world of business included a few heavyweights whose impact can still be felt, some more than others. They include:

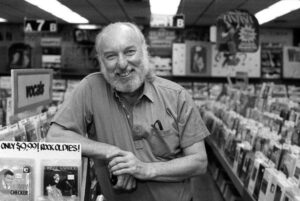

Russ Solomon

Russ Solomon

He took his little music store on Watts Street in Sacramento – opened in 1960 and named after his father’s drug store, which in turn had been named for a theater on its block – and transformed that tiny shop specializing in LP's and 45's into the mighty Tower Records, the largest distributor of music in the world. In its day, Tower was far more than a bricks-and-mortar retailer. It was nerve center. It was a place to be, a place to be seen, and a place to learn; what was cool, what was hot, and, above all, where music – if not all of America – was headed.

David Edgerton

David Edgerton

In March of 1954, he took a small, failing Miami-based food chain – Insta Burger King – reimagined it, re-named it, and reinvented just how it went about the business of making and selling its product. Included in the transfer was a device he found being used in one particular Insta Burger King location, a device that Edgerton made central to his rechristened fast food chain. He then compelled all 250 of his franchisees to install an “Insta Broiler,” a device that gave a frozen burger a distinctive grilled flavor that frying, quite simply, lacked. And Edgerton’s Insta Broiler would soon become the heart and soul of his boldly reimagined company, Burger King.

Hubert de Givenchy

Hubert de Givenchy

The creator of the Paris fashion house that bears his name, his revolutionary yet elegantly minimal designs were built around, in the words of his company’s website, “spare lines, slender hips, slim silhouettes and swan-like necks.” And while actresses all over the world would soon be flocking to him for one of his originals, it was one actress in particular – Audrey Hepburn – who’d emerge as his flesh-and-blood easel. As a result, her stunning black dress in the opening credits of Breakfast at Tiffany’s may remain to this day the greatest commercial of all time. At the very least, it stole an iconic movie scene from the likes of Hepburn, Henry Mancini and even Tiffany’s itself.

Ella Brennan

Ella Brennan

The “Grand Dame” of New Orleans cooking who transformed a so-so Garden District eatery into the world-famous Commander’s Palace, and who turned the world on to such delicacies as turtle soup and an exotic cocktail called a Sezarac. Brennan, whose first job was in Bourbon Street's legendary Old Absinthe House, was also the first to tout Louisiana cooking, in both its countrified Cajun and refined Creole forms, as a world-class cuisine. Nicknamed “Hurricane Ella” for her demanding ways, her legacy was cemented 70 years ago, the night her restaurateur older brother told her to come up with a new desert for him. Working with the house chef, and noticing a bunch of bananas sitting on the counter, she sautéed the bananas in butter, finished them by adding in rum and banana liqueur, lit the mixture on fire, and then sprinkled in dashes of cinnamon, before pouring the entire concoction over vanilla ice cream. Voila. Not just a legend, but a New Orleans dessert for the ages; Bananas Foster.

Ted Dabney

Ted Dabney

He was not just the power behind the throne, he was the circuitry. When Dabney and partner Nolan Bushnell, launched Atari in 1972, the company that introduced the world to video games, it was with the understanding that Dabney would be the product designer and engineer and Bushnell the company's front man and marketer. So when, cobbling together some wiring, some old television components and some cheap wooden paneling, Dabney built not only the electronics and trademark sound behind the legendary arcade game, Pong, but designed and constructed its signature casing based on the typical space between most bars’ jukebox and pinball machine,  Bushnell ran with it. Unfortunately for the meek and mild-mannered Dabney, he ran a bit too far, copywriting the technology for himself and omitting his partner’s name entirely. Bushnell then ousted Dabney, paying him a mere $250,000 to go away. Before doing so, however, Dabney also designed a video-and-technology-themed kids restaurant for his soon-to-be-former partner that in time became Chuck E. Cheese. While millions continue to consider Nolan Bushnell the “Father of the Video Game,” anyone with an even marginal sense of fair play, if not human decency, hopes that at some point that one tiny paragraph of pop culture history might, somehow, someway, be rewritten as it should.

Bushnell ran with it. Unfortunately for the meek and mild-mannered Dabney, he ran a bit too far, copywriting the technology for himself and omitting his partner’s name entirely. Bushnell then ousted Dabney, paying him a mere $250,000 to go away. Before doing so, however, Dabney also designed a video-and-technology-themed kids restaurant for his soon-to-be-former partner that in time became Chuck E. Cheese. While millions continue to consider Nolan Bushnell the “Father of the Video Game,” anyone with an even marginal sense of fair play, if not human decency, hopes that at some point that one tiny paragraph of pop culture history might, somehow, someway, be rewritten as it should.

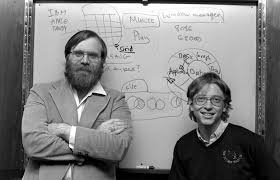

Paul Allen

Paul Allen

If he had only been the father of home computing, the guy who convinced Bill Gates to drop out of Harvard to help him start a software company, he’d be listed here. And if he’d only co-founded Microsoft or personally named it (by mashing up microcomputer and software), he be listed. But after holding onto 36% of the company for as long as it took it to go public, something that overnight allowed him to become one of the richest men in the world, Paul Allen really seemed to catch fire, while spitting in the very face of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s tired old notion that “there are no second acts in American life.” He quickly set up organizations to research and study the unknown (Allen Institute for Brain Science, Institute for Artificial Intelligence). He invested heavily in technology startups (Vulcan Capital). He funded the exploration of outer space and suborbital space travel (Mojave Aerospace Ventures). He bought media companies and used them as living labs to study the matrix of content and connectivity (Charter Communications, Home Shopping Network). He became so  enamored with musicians and their live performances he bought Ticketmaster. He funded an expedition to recover the bell of the H.M.S. Hood, the British warship whose unexpected sinking was immortalized in Johnny Horton’s hit 1959 song, Sink the Bismarck. He bought pro sports teams (Portland Trailblazers, Seattle Seahawks). He built sports arenas (CitiLink Field). He produced feature length Hollywood movies (Far From Heaven, Rock Candy). He donated over $2 billion in support of arts, education and conservation initiatives, including the Great Elephant Census, in which a baseline of the world’s elephant population was created, while personally fighting against the sale of products made from endangered species, like elephants, rhinos, lions, tigers, leopards, cheetahs and marine turtles. He collected priceless art. He taught himself the guitar, started a rock band, and jammed onstage with the likes of Stevie Wonder, Joe Walsh and Ringo Starr. And, among so many other things, he opened the Museum of Pop Culture, designed by Frank Gehry and originally intended to look like a giant version of the guitar favored by his hero and fellow Seattle boy, Jimi Hendrix. In a world overrun with those all-too-willing to hawk seminars, self-help aids and pithy books designed to make you tons of money, Paul Allen did something refreshingly different and far more valuable. He staged a 30-year free clinic on how to live once you do it.

enamored with musicians and their live performances he bought Ticketmaster. He funded an expedition to recover the bell of the H.M.S. Hood, the British warship whose unexpected sinking was immortalized in Johnny Horton’s hit 1959 song, Sink the Bismarck. He bought pro sports teams (Portland Trailblazers, Seattle Seahawks). He built sports arenas (CitiLink Field). He produced feature length Hollywood movies (Far From Heaven, Rock Candy). He donated over $2 billion in support of arts, education and conservation initiatives, including the Great Elephant Census, in which a baseline of the world’s elephant population was created, while personally fighting against the sale of products made from endangered species, like elephants, rhinos, lions, tigers, leopards, cheetahs and marine turtles. He collected priceless art. He taught himself the guitar, started a rock band, and jammed onstage with the likes of Stevie Wonder, Joe Walsh and Ringo Starr. And, among so many other things, he opened the Museum of Pop Culture, designed by Frank Gehry and originally intended to look like a giant version of the guitar favored by his hero and fellow Seattle boy, Jimi Hendrix. In a world overrun with those all-too-willing to hawk seminars, self-help aids and pithy books designed to make you tons of money, Paul Allen did something refreshingly different and far more valuable. He staged a 30-year free clinic on how to live once you do it.

Wayne Huizenga

Wayne Huizenga

He built a Fortune 500 company, Waste Management, from a single garbage truck, he spun a handful of video stores into Blockbuster Video, which he then flipped to Viacom for billions just before the home video market cratered, and he bought a small enterprise, Auto Nation, USA, and turned it into AutoNation, a giant nationwide retailer that, by the time of his death, had sold over 12 million cars and counting in under 20 years. Yet, much like the gruff central character in Born Yesterday, the Illinois-born garbage collector was an often reviled public figure  whose success always seemed eclipsed by his less-than-cuddly junkman demeanor. In the late 90's, as founder and owner of the Florida Marlins – one of three South Florida pro sports franchises he owned, along with the Florida Panthers and Miami Dolphins – he was booed unmercifully at local sporting events for having ordered GM Dave Dombrowski to sell off the Marlins’ most expensive players just weeks after they captured the 1997 World Series. Like just about everything else in his life, however, that wholesale selloff of assets still inflated by the halo effect of a World Series – and as unpopular as it may have been across the country, and even Huizenga later apologized for it – would be later seen by experts as a brilliant business, and maybe even baseball decision, because many of the young, high-ceiling players that Dombrowski received would serve as the core of the Marlins next world championship just six years later.

whose success always seemed eclipsed by his less-than-cuddly junkman demeanor. In the late 90's, as founder and owner of the Florida Marlins – one of three South Florida pro sports franchises he owned, along with the Florida Panthers and Miami Dolphins – he was booed unmercifully at local sporting events for having ordered GM Dave Dombrowski to sell off the Marlins’ most expensive players just weeks after they captured the 1997 World Series. Like just about everything else in his life, however, that wholesale selloff of assets still inflated by the halo effect of a World Series – and as unpopular as it may have been across the country, and even Huizenga later apologized for it – would be later seen by experts as a brilliant business, and maybe even baseball decision, because many of the young, high-ceiling players that Dombrowski received would serve as the core of the Marlins next world championship just six years later.

Music Deaths of 2018

Sports Deaths of 2018

Actor Deaths of 2018