Please enjoy part two of my four-part list of 40 people who died this year whose lives, legacies and passings were given short shrift by far too many in the mainstream media.

Please enjoy part two of my four-part list of 40 people who died this year whose lives, legacies and passings were given short shrift by far too many in the mainstream media.

30. Charles “Skip” Pitts

He was a talented session man and a Memphis-based guitarist who scratchy, bold playing style helped lend the Isley Brothers’ It’s Your Thing its unmistakable and unique blend of soul, funk and rock, not to mention its funky lead guitar riff. But it wasn’t until Pitts, an acknowledged master of the wah-wah pedal, recorded a certain movie theme for director Gordon Parks that he left not just his mark, but an indelible impression, on the face of pop culture in America. Because in 1971 it was Pitts’ distinctive, repetitive and slightly distorted wah-wah guitar that helped turn Isaac Hayes' Theme from Shaft into one of the defining musical moments and one of the most important pieces of recorded music of the entire 20th Century, and in the process helped change the sound, look, feel and direction of pop, soul and funk music forever.

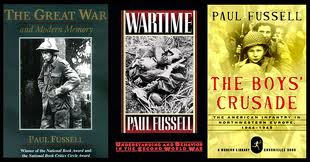

29. Paul Fussell

One of the most insightful, courageous and bare-knuckled essayists in the history of American letters. Talk about a dying breed; an observer of life with no axe to grind, no hidden agenda and, best of all, balls the size of watermelons; a man of letters who went to the office each morning armed with little more than a keen eye, a sharp wit, and the courage of his convictions. A decorated World War II veteran who earned two purple hearts and  a bronze star, Fussell wrote with great insight about everything from penis size to the Boy Scout Handbook. But he was at his best when writing about something with which he was all too acquainted; war. His epic chronicle of World War I is a must-read for anyone considering declaring, going to, or even discussing war. Fussell’s graphic, unflinching descriptions can often make it physically difficult, if not impossible, to read; what with your hands shaking, your mind numbing, and your eyes filling with tears, as they invariably will. Fussell not only wrote about the physical toll war extracted on a country and its people, but its hidden costs as well, which often

a bronze star, Fussell wrote with great insight about everything from penis size to the Boy Scout Handbook. But he was at his best when writing about something with which he was all too acquainted; war. His epic chronicle of World War I is a must-read for anyone considering declaring, going to, or even discussing war. Fussell’s graphic, unflinching descriptions can often make it physically difficult, if not impossible, to read; what with your hands shaking, your mind numbing, and your eyes filling with tears, as they invariably will. Fussell not only wrote about the physical toll war extracted on a country and its people, but its hidden costs as well, which often  came due in the form of things like “intellect, discrimination, honesty, individuality, complexity, ambiguity and irony, not to mention privacy and wit.”

came due in the form of things like “intellect, discrimination, honesty, individuality, complexity, ambiguity and irony, not to mention privacy and wit.”

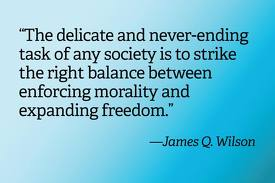

28. James Q. Wilson

28. James Q. Wilson

One of the most important social scientists of the 20th Century, Wilson radically changed how we view urban decay. His 1982 essay, “Broken Windows,” which he co-authored, contends officials shouldn’t try to fix blighted cities by attacking macro issues like drugs, gangs and violent crimes, but by focusing on smaller, social order concerns like winos, panhandlers, graffiti and, yes, broken windows. Wrote Wilson, “Social psychologists and police officers tend to agree that if a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken.” The author called vandalism and graffiti “signal crimes”  and said that if they were kept in check, residents would soon start to feel more positive about their city and their attitude would begin to manifest itself upward and outward. Wilson was the main reason why in the early 90s mayors like Rudy Giuliani in New York and Richard Daley in Chicago began attacking smaller crimes like parking violations, subway graffiti and litter, and launched initiatives to beautify and bring art, culture and flora to public spaces. And take it from someone who lived in both cities, the impact was staggering. And while some long-time residents contend that such police heavy-handedness robbed their towns of much of their individuality and color, and could at times appear almost fascist in its execution, one could not argue with the results. As former Upper West Side resident and Seinfeld creator Larry David once told a neighbor of mine, “Yeah, there’s a little less local color around here these days. But c’mon, what would you rather have next door, a Patagonia or a crack house?”

and said that if they were kept in check, residents would soon start to feel more positive about their city and their attitude would begin to manifest itself upward and outward. Wilson was the main reason why in the early 90s mayors like Rudy Giuliani in New York and Richard Daley in Chicago began attacking smaller crimes like parking violations, subway graffiti and litter, and launched initiatives to beautify and bring art, culture and flora to public spaces. And take it from someone who lived in both cities, the impact was staggering. And while some long-time residents contend that such police heavy-handedness robbed their towns of much of their individuality and color, and could at times appear almost fascist in its execution, one could not argue with the results. As former Upper West Side resident and Seinfeld creator Larry David once told a neighbor of mine, “Yeah, there’s a little less local color around here these days. But c’mon, what would you rather have next door, a Patagonia or a crack house?”

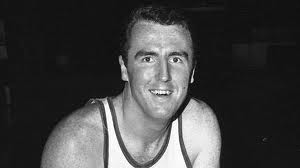

27. Kenny Heitz

27. Kenny Heitz

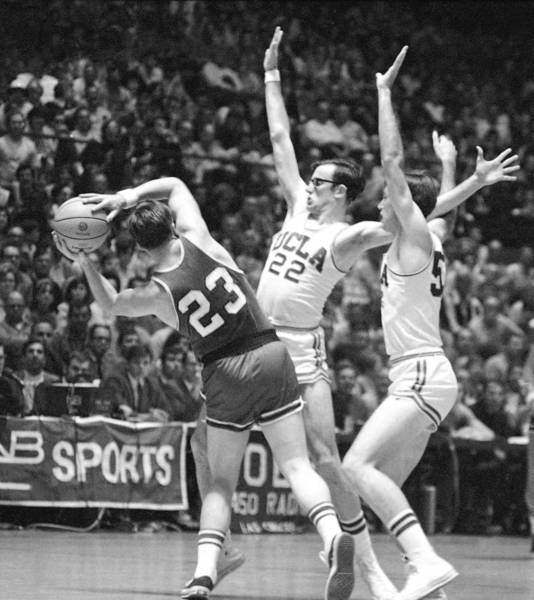

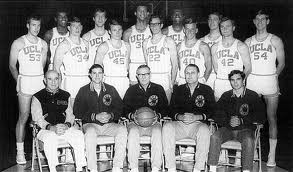

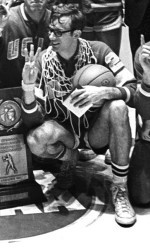

It would be easy to say Heitz was in the right place at the right time. He did, after all, enter UCLA in the fall of 1965 and become teammates on the freshman team with high school greats Lucius Allen, Lynn Shackleford, and a 7’2” giant named Lew Alcindor, the single most dominant player to ever set foot on a college court. He then started alongside Allen, Shackleford, and Alcindor on the freshman team that a few weeks later would christen an all-new Pauley Pavilion by trouncing the  UCLA varsity 75-60 in a season-opening exhibition – just seven months, mind you, after that same varsity squad won the national championship. And along the way became, with the other three, the first player in history to win three consecutive NCAA titles; doing so with a career win/loss record of 88-2. But Heitz was more than lucky. He was smart and disciplined. And on the court was relentless. As the point-man on coach John Wooden’s famed full-court trap press, Heitz played the pivotal role as the middle man, the player responsible for doggedly forcing the opposing ball-handler into one of the two corners and, in essence, “trapping” him between two defenders and the sideline. And that was Heitz’s game; stifling, almost suffocating defense. As a humble, polite, bookish kid who always played with manicured hair and horned-rimmed glasses, the UCLA fans claimed that while he may have looked like Clark Kent, he played like Superman. And perhaps the contest that symbolized Heitz’s career at UCLA was his last one as a

UCLA varsity 75-60 in a season-opening exhibition – just seven months, mind you, after that same varsity squad won the national championship. And along the way became, with the other three, the first player in history to win three consecutive NCAA titles; doing so with a career win/loss record of 88-2. But Heitz was more than lucky. He was smart and disciplined. And on the court was relentless. As the point-man on coach John Wooden’s famed full-court trap press, Heitz played the pivotal role as the middle man, the player responsible for doggedly forcing the opposing ball-handler into one of the two corners and, in essence, “trapping” him between two defenders and the sideline. And that was Heitz’s game; stifling, almost suffocating defense. As a humble, polite, bookish kid who always played with manicured hair and horned-rimmed glasses, the UCLA fans claimed that while he may have looked like Clark Kent, he played like Superman. And perhaps the contest that symbolized Heitz’s career at UCLA was his last one as a  player. In the finals against Purdue All-American Rick Mount, one of the greatest shooters in the history of the game, and a kid who that year averaged over 35 points a game, Heitz was a ball-hawking terror. Hounding Mount all day long and all over the court, he relentlessly harassed the Indiana scoring legend into the single worst shooting performance of his college career, and at one point the usually dead-eyed Mount misfired 14 straight times. Afterward, Alcindor, who had scored 37 points, was named MVP. Kenny Heitz, it was later discovered, was runner up in the voting. He didn't score a single point.

player. In the finals against Purdue All-American Rick Mount, one of the greatest shooters in the history of the game, and a kid who that year averaged over 35 points a game, Heitz was a ball-hawking terror. Hounding Mount all day long and all over the court, he relentlessly harassed the Indiana scoring legend into the single worst shooting performance of his college career, and at one point the usually dead-eyed Mount misfired 14 straight times. Afterward, Alcindor, who had scored 37 points, was named MVP. Kenny Heitz, it was later discovered, was runner up in the voting. He didn't score a single point.

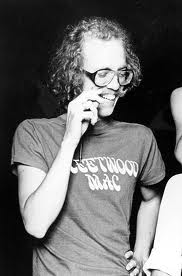

26. Bob Welch

At some point between being Peter Green’s band and being Lindsay Buckingham and Stevie Nicks’ band – that is, at some point between being a principled but struggling blues outfit and the most commercially viable rock  entity on Earth – Fleetwood Mac was Bob Welch’s band. No, Welch wasn’t a musical genius, or even a very good guitarist. What he was, was a unique singer/songwriter with a muse unlike almost any other. His songs, while non-traditional in structure and often slightly off-kilter, nevertheless employed musical hooks that often had the ability to wrap themselves around your brain, heart, soul or whatever, and simply not let go. When he was good, like he was with Sentimental Lady from the Bare Trees album, he was a hypnotic blend of California cool and new-age whimsical. And when he was bad he could devolve into some toxic mix of ponderous and plodding. But every now and then – such as his often overlooked Silver Heels on the Heroes Are Hard to Find album, or

entity on Earth – Fleetwood Mac was Bob Welch’s band. No, Welch wasn’t a musical genius, or even a very good guitarist. What he was, was a unique singer/songwriter with a muse unlike almost any other. His songs, while non-traditional in structure and often slightly off-kilter, nevertheless employed musical hooks that often had the ability to wrap themselves around your brain, heart, soul or whatever, and simply not let go. When he was good, like he was with Sentimental Lady from the Bare Trees album, he was a hypnotic blend of California cool and new-age whimsical. And when he was bad he could devolve into some toxic mix of ponderous and plodding. But every now and then – such as his often overlooked Silver Heels on the Heroes Are Hard to Find album, or  the downright stunning Hypnotized on Mystery to Me – Welch became something else altogether. He raised his game to a level that bordered on greatness. And when he did that, he could craft a pop tune that could stand toe-to-toe with anything – and I mean anything – that Fleetwood Mac ever did. In fact, for my money the band never recorded a single song any finer or any more timeless than Hypnotized – a laid back groovefest composed by Welch and featuring some subtle, almost painfully beautiful guitar work by another forgotten band member, Bob Weston – who, likewise, died this year, and who with Welch were the only two full-time members of Fleetwood Mac’s checkered roster of ex-players not invited to participate when the band got inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Which is a shame, because even Mick Fleetwood admits that Bob Welch was the glue that held Fleetwood Mac together during a dark and potentially life-threatening period for the group; a feat which, alone, should have earned him a spot onstage along with his richer, more acclaimed and far more famous former bandmates.

the downright stunning Hypnotized on Mystery to Me – Welch became something else altogether. He raised his game to a level that bordered on greatness. And when he did that, he could craft a pop tune that could stand toe-to-toe with anything – and I mean anything – that Fleetwood Mac ever did. In fact, for my money the band never recorded a single song any finer or any more timeless than Hypnotized – a laid back groovefest composed by Welch and featuring some subtle, almost painfully beautiful guitar work by another forgotten band member, Bob Weston – who, likewise, died this year, and who with Welch were the only two full-time members of Fleetwood Mac’s checkered roster of ex-players not invited to participate when the band got inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Which is a shame, because even Mick Fleetwood admits that Bob Welch was the glue that held Fleetwood Mac together during a dark and potentially life-threatening period for the group; a feat which, alone, should have earned him a spot onstage along with his richer, more acclaimed and far more famous former bandmates.

25. Dan O’Keefe

In 1966, a young writer, Reader’s Digest editor and incurable romantic named Dan O’Keefe wanted to somehow commemorate his first date with his wife. To that end, O’Keefe conceived and then named for his young family their very own personal holiday, and over the years would use that holiday as a wild card, moving it at various points throughout the year, whenever some combination of need, circumstance, whimsy or fate required – but  more often than not, whenever tension simply determined the O’Keefes needed a break. They eventually started calling their little roving holiday Festivus, a word that one day just popped into Dan’s head, but which in retrospect he felt sounded both celebratory and just a little Greek or Roman. By now you probably can figure out the rest of the story, especially if you’re a fan of the most beloved and influential sitcom since The Honeymooners. Dan’s son, little Dan Junior, would eventually grow up, would eventually become a television writer, and would eventually find work on the hit TV series Seinfeld. Then one day he decided to reach back into his family’s personal history and dust off his dad’s peculiar little brainchild, name and all. And while Dan Junior eventually changed the date of Festivus

more often than not, whenever tension simply determined the O’Keefes needed a break. They eventually started calling their little roving holiday Festivus, a word that one day just popped into Dan’s head, but which in retrospect he felt sounded both celebratory and just a little Greek or Roman. By now you probably can figure out the rest of the story, especially if you’re a fan of the most beloved and influential sitcom since The Honeymooners. Dan’s son, little Dan Junior, would eventually grow up, would eventually become a television writer, and would eventually find work on the hit TV series Seinfeld. Then one day he decided to reach back into his family’s personal history and dust off his dad’s peculiar little brainchild, name and all. And while Dan Junior eventually changed the date of Festivus  to December 23 for purposes of his Seinfeld script, and added the Festivus pole, the “feats of strength” and the “airing of grievances” for comedic effect, not everything he wrote for the episode was a product of his imagination. One year he recalled, for example, after the death of his grandmother, that his father woke up one morning and determined he needed Festivus to help him deal with the loss of his mother. Later that evening the elder O’Keefe stood up at the dinner table, and offered a toast to his remaining family members, all gathered around him. He raised his glass, smiled, and offered simply, “A Festivus for the rest of us!”

to December 23 for purposes of his Seinfeld script, and added the Festivus pole, the “feats of strength” and the “airing of grievances” for comedic effect, not everything he wrote for the episode was a product of his imagination. One year he recalled, for example, after the death of his grandmother, that his father woke up one morning and determined he needed Festivus to help him deal with the loss of his mother. Later that evening the elder O’Keefe stood up at the dinner table, and offered a toast to his remaining family members, all gathered around him. He raised his glass, smiled, and offered simply, “A Festivus for the rest of us!”

24. Eve Arnold

It would be a horrible injustice to call Arnold one of the most important female photographers of the 20th Century. She was simply one of the most important photographers, period. Arnold had a unique way of capturing  the humanity, even the vulnerability, of a person – especially those who often seem bound and determined to show the world anything but. Her most celebrated subject, of course, was Marilyn Monroe. And her photos of the ill-fated star on the set of her ill-fated film The Misfits – while if they’d not been able to specifically foretell the pending demise of her marriage to the film’s writer, Arthur Miller, or, in time, her tragic and horribly suspicious death – at least offered telling glimpses of what darkness, pain and suffering lie ahead.

the humanity, even the vulnerability, of a person – especially those who often seem bound and determined to show the world anything but. Her most celebrated subject, of course, was Marilyn Monroe. And her photos of the ill-fated star on the set of her ill-fated film The Misfits – while if they’d not been able to specifically foretell the pending demise of her marriage to the film’s writer, Arthur Miller, or, in time, her tragic and horribly suspicious death – at least offered telling glimpses of what darkness, pain and suffering lie ahead.  But Eve Arnold didn’t simply shoot the famous. She was a photojournalist of the highest order, and her stunning, even moving black-and-white images ranging from things like neo-Nazi rallies, the institutionalized, the poor, the mentally ill, and China under Chairman Mao, to a

But Eve Arnold didn’t simply shoot the famous. She was a photojournalist of the highest order, and her stunning, even moving black-and-white images ranging from things like neo-Nazi rallies, the institutionalized, the poor, the mentally ill, and China under Chairman Mao, to a  young, dashing and ferociously determined Malcolm X, reveal that just as in the case of titans of the lens like Margaret Bourke White, Diane Arbus, Vivian Maier, Dorothea Lange and even Annie Leibovitz, when it comes to being able to capture the essence of a man on film, women take a back seat to no one.

young, dashing and ferociously determined Malcolm X, reveal that just as in the case of titans of the lens like Margaret Bourke White, Diane Arbus, Vivian Maier, Dorothea Lange and even Annie Leibovitz, when it comes to being able to capture the essence of a man on film, women take a back seat to no one.

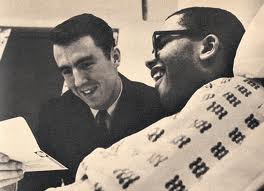

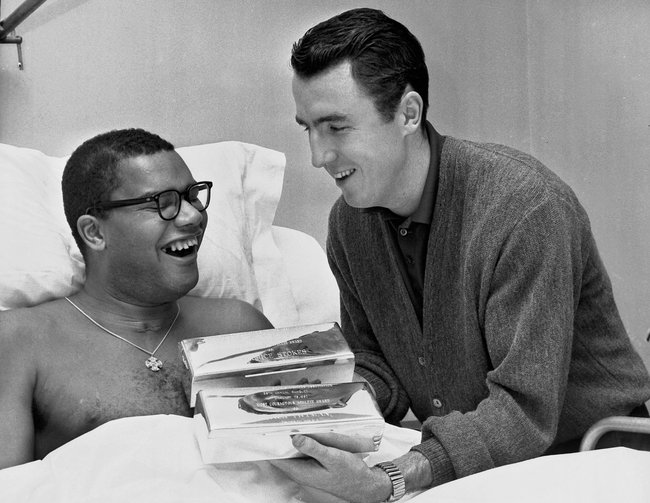

23. Jack Twyman

23. Jack Twyman

In the spring of 1958, during the Cincinnati Royals final game of the regular season, 24-year old Maurice Stokes, a talented and powerful black forward from one of the poorest sections of Pittsburgh, went up for a rebound, had his feet cut out from underneath him, and crashed to the floor, directly on his head.  Three days later, following an opening-round playoff game in Detroit, Stokes told a teammate on the plane home that he felt he was going to die. Moments later the massive young All Star slumped over, fell unconscious, and lapsed into a deep coma. When he finally awoke in the hospital days later, his left side was paralyzed, his ability to speak was gone, and his NBA career was over. Initially, support for Stokes was strong as players from around the NBA kept dropping by and visiting. But soon that support began to wane as, at least for those other players, life returned to normal. Only one person continued to visit, and kept doing so every day; Jack Twyman, a fellow Royal and another kid from Pittsburgh. The difference was Twyman was white and from a far nicer side of town. That first year, when it became obvious that his bills

Three days later, following an opening-round playoff game in Detroit, Stokes told a teammate on the plane home that he felt he was going to die. Moments later the massive young All Star slumped over, fell unconscious, and lapsed into a deep coma. When he finally awoke in the hospital days later, his left side was paralyzed, his ability to speak was gone, and his NBA career was over. Initially, support for Stokes was strong as players from around the NBA kept dropping by and visiting. But soon that support began to wane as, at least for those other players, life returned to normal. Only one person continued to visit, and kept doing so every day; Jack Twyman, a fellow Royal and another kid from Pittsburgh. The difference was Twyman was white and from a far nicer side of town. That first year, when it became obvious that his bills  would outstrip Stokes’ ability to pay them, Twyman pitched in and arranged for a charity basketball game in the Catskills, which in turn generated over $100,000. The next year he did the same thing; and the year after that, and the year after that. Eventually Twyman’s little exhibition became an annual affair known as the Stokes game, and each year he would organize and run it, even as he continued his own career as a player and broadcaster. But it was not nearly enough. So when it became clear that his teammate needed additional help, and not just physical and emotional help, but financial help as well, Twyman, with his wife’s blessing, adopted the wheelchair-bound young black man and had himself appointed his legal guardian; something he remained until Stokes’ death at the age of 36. I guess it would be easy for me, an old Royal fan, to remember Twyman as the first player in NBA history to average 30 points a game for a season, or as a six-time All Star and Hall of

would outstrip Stokes’ ability to pay them, Twyman pitched in and arranged for a charity basketball game in the Catskills, which in turn generated over $100,000. The next year he did the same thing; and the year after that, and the year after that. Eventually Twyman’s little exhibition became an annual affair known as the Stokes game, and each year he would organize and run it, even as he continued his own career as a player and broadcaster. But it was not nearly enough. So when it became clear that his teammate needed additional help, and not just physical and emotional help, but financial help as well, Twyman, with his wife’s blessing, adopted the wheelchair-bound young black man and had himself appointed his legal guardian; something he remained until Stokes’ death at the age of 36. I guess it would be easy for me, an old Royal fan, to remember Twyman as the first player in NBA history to average 30 points a game for a season, or as a six-time All Star and Hall of  Famer. Or maybe for me to remember him for one of the most dramatic moments I ever witnessed live on television when, as color man for ABC prior to Game Seven of the 1970 finals between New York and Los Angeles, Twyman looked to his left, saw injured superstar Willis Reed – who had been ruled out of the game and was not expected to play – hobbling out of the Knick locker room in full uniform, stopped his train of thought, turned away from play-by-play man Chris Schenkel, and announced clearly and distinctly, even as the roar in Madison Square Garden began to rock the rafters and I felt the hairs on the back of my neck begin to rise, “I think we see Willis coming out.” Remembering him for any or all of that kind of stuff would be easy; even understandable. But personally, I’ll remember the man for these two simple but immutable truths: Jack Twyman was, quietly and with little fanfare, the single greatest teammate I've ever seen in the history of sports. But even more than that – far more, in fact – in a decade in which race would become both a dividing and defining issue for an entire generation of young, impressionable American minds, more than my parents, more than the nuns at school, more than any book I ever read, or TV show or movie I ever watched, Jack Twyman taught me more about loving my fellow man, regardless of color, than any person I ever knew.

Famer. Or maybe for me to remember him for one of the most dramatic moments I ever witnessed live on television when, as color man for ABC prior to Game Seven of the 1970 finals between New York and Los Angeles, Twyman looked to his left, saw injured superstar Willis Reed – who had been ruled out of the game and was not expected to play – hobbling out of the Knick locker room in full uniform, stopped his train of thought, turned away from play-by-play man Chris Schenkel, and announced clearly and distinctly, even as the roar in Madison Square Garden began to rock the rafters and I felt the hairs on the back of my neck begin to rise, “I think we see Willis coming out.” Remembering him for any or all of that kind of stuff would be easy; even understandable. But personally, I’ll remember the man for these two simple but immutable truths: Jack Twyman was, quietly and with little fanfare, the single greatest teammate I've ever seen in the history of sports. But even more than that – far more, in fact – in a decade in which race would become both a dividing and defining issue for an entire generation of young, impressionable American minds, more than my parents, more than the nuns at school, more than any book I ever read, or TV show or movie I ever watched, Jack Twyman taught me more about loving my fellow man, regardless of color, than any person I ever knew.

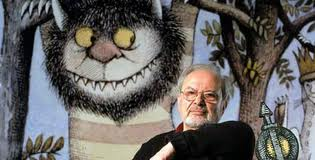

22. Maurice Sendak

22. Maurice Sendak

As a young boy he was a talented, sensitive, even meek and often taunted Jew/Polack living in a very unforgiving, rough-and-tumble part of Brooklyn; a kid who, by the way, also happened to be gay. What’s more, he grew up transfixed by the constant radio reports of such horrors-of-the-day as the Lindbergh baby kidnapping, the Leopold and Loeb murder trial, the Great Depression and, eventually, World War II, before and during which he lost virtually all his extended family to the Holocaust. So how in God’s name, when he started working as a children’s book author and illustrator a  decade or so later, could anyone blame Maurice Sendak when so many of his characters ended up being hairy, horned, fanged, wide-eyed monsters? If Sendak had only written and illustrated one book in his time, that book – 1964’s Where the Wild Things Are – would have assured him cultural immortality. It was that revolutionary, that impactful, and resonated that deeply with kids everywhere; in fact, nearly a half century later, still does. But he ended up writing and/or illustrating over 100 other books in a career that spanned seven decades, many of them classics in their own right. Perhaps the reason that kids love Maurice Sendak so much is that, like Dr. Seuss, he liked them. And he respected them.

decade or so later, could anyone blame Maurice Sendak when so many of his characters ended up being hairy, horned, fanged, wide-eyed monsters? If Sendak had only written and illustrated one book in his time, that book – 1964’s Where the Wild Things Are – would have assured him cultural immortality. It was that revolutionary, that impactful, and resonated that deeply with kids everywhere; in fact, nearly a half century later, still does. But he ended up writing and/or illustrating over 100 other books in a career that spanned seven decades, many of them classics in their own right. Perhaps the reason that kids love Maurice Sendak so much is that, like Dr. Seuss, he liked them. And he respected them.  Maybe it was because, as he once told Terry Gross on her interview program, Fresh Air, he never really wrote specifically with them in mind. But just maybe it was because he had faith in his readers’ ability to wrap their little brains around such grown-up and universally human concepts as uncertainty, innuendo, anger, revenge, fear, darkness and others – concepts that he took head on, but ones that more sugary-sweet and rosy-cheeked authors and animators wouldn’t touch on a dare. "Do parents sit down and tell their kids everything? I don't know. I don't know," he told Gross in the last of the seven times she had him on her show over the years. "I've convinced myself -- I hope I'm right -- that children despair of you if you don't tell them the truth."

Maybe it was because, as he once told Terry Gross on her interview program, Fresh Air, he never really wrote specifically with them in mind. But just maybe it was because he had faith in his readers’ ability to wrap their little brains around such grown-up and universally human concepts as uncertainty, innuendo, anger, revenge, fear, darkness and others – concepts that he took head on, but ones that more sugary-sweet and rosy-cheeked authors and animators wouldn’t touch on a dare. "Do parents sit down and tell their kids everything? I don't know. I don't know," he told Gross in the last of the seven times she had him on her show over the years. "I've convinced myself -- I hope I'm right -- that children despair of you if you don't tell them the truth."

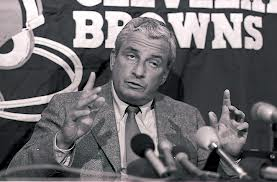

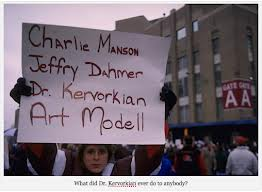

21. Art Modell

All legacies are not created equal. Take former Browns owner Art Modell. Sure he moved the team out of Cleveland, broke millions of hearts, and got vilified for his efforts. But most don't know the backstory. Modell, an ambitious Jewish kid from Brooklyn who cut his teeth in advertising, bought the team in 1961 for $4 million, using only $250,000 of his own money. Then a few years later, when the Browns’ stadium became too costly for its owner, the cash-strapped city, to maintain, Modell rode to the rescue, said he would maintain it if Cleveland leased the stadium to a holding company he formed for $1 a year, which they agreed to do. He then sublet Municipal Stadium back to

All legacies are not created equal. Take former Browns owner Art Modell. Sure he moved the team out of Cleveland, broke millions of hearts, and got vilified for his efforts. But most don't know the backstory. Modell, an ambitious Jewish kid from Brooklyn who cut his teeth in advertising, bought the team in 1961 for $4 million, using only $250,000 of his own money. Then a few years later, when the Browns’ stadium became too costly for its owner, the cash-strapped city, to maintain, Modell rode to the rescue, said he would maintain it if Cleveland leased the stadium to a holding company he formed for $1 a year, which they agreed to do. He then sublet Municipal Stadium back to  the Browns and Indians for full value – with half the rent money going to his holding company and half going straight into his pocket. Modell next built luxury suites, which made revenues soar. But, while he split proceeds from NFL games with the Browns, he pocketed 100% of money from the baseball games, sharing none of it with the Indians. Two decades later the Tribe, fed up with the one-sided deal, decided to build a baseball-only stadium in town which included, of course, luxury suites –

the Browns and Indians for full value – with half the rent money going to his holding company and half going straight into his pocket. Modell next built luxury suites, which made revenues soar. But, while he split proceeds from NFL games with the Browns, he pocketed 100% of money from the baseball games, sharing none of it with the Indians. Two decades later the Tribe, fed up with the one-sided deal, decided to build a baseball-only stadium in town which included, of course, luxury suites –  putting a major dent in Modell’s revenue model and making his sweet deal look a lot less sweet. So he demanded the city use taxpayer money to refurbish his decaying old ballpark – something Cleveland begrudgingly did for fear of losing the Browns. But not before a neighboring community offered to build a new, state-of-the-art stadium for Modell just miles from the old one. He turned them down cold because it would mean an end to his $1 lease deal with Cleveland. However, even as all this was going on, and as the cash-strapped

putting a major dent in Modell’s revenue model and making his sweet deal look a lot less sweet. So he demanded the city use taxpayer money to refurbish his decaying old ballpark – something Cleveland begrudgingly did for fear of losing the Browns. But not before a neighboring community offered to build a new, state-of-the-art stadium for Modell just miles from the old one. He turned them down cold because it would mean an end to his $1 lease deal with Cleveland. However, even as all this was going on, and as the cash-strapped  Cleveland was bending over backward to try to accommodate him, Modell began secretly negotiating with Baltimore for an even more profitable deal. Forget he had promised fans and public officials many times over he’d never take the Browns out of Cleveland. Forget he had once vilified Colts owner Robert Irsay for sneaking his club out of town under the shadow of night for Indianapolis. Hell, forget he was the NFL’s most vocal backer of a lawsuit to prevent Oakland owner Al Davis from moving the Raiders to Los Angeles, and even testified on the league’s behalf. None of that mattered. Once Modell got his mega-deal and earned himself yet another huge payoff, he and Cleveland’s

Cleveland was bending over backward to try to accommodate him, Modell began secretly negotiating with Baltimore for an even more profitable deal. Forget he had promised fans and public officials many times over he’d never take the Browns out of Cleveland. Forget he had once vilified Colts owner Robert Irsay for sneaking his club out of town under the shadow of night for Indianapolis. Hell, forget he was the NFL’s most vocal backer of a lawsuit to prevent Oakland owner Al Davis from moving the Raiders to Los Angeles, and even testified on the league’s behalf. None of that mattered. Once Modell got his mega-deal and earned himself yet another huge payoff, he and Cleveland’s  beloved Browns were off for Baltimore. For the final game there were more people outside Municipal Stadium in protest than inside watching football. And on the NFL Today, Mike Ditka not only said Cleveland had the best fans in the NFL and that they didn’t deserve such treatment, he went so far as to say that if Art Modell had any honor at all he would have sold the team to a local owner. But perhaps the best response came from Cleveland native and

beloved Browns were off for Baltimore. For the final game there were more people outside Municipal Stadium in protest than inside watching football. And on the NFL Today, Mike Ditka not only said Cleveland had the best fans in the NFL and that they didn’t deserve such treatment, he went so far as to say that if Art Modell had any honor at all he would have sold the team to a local owner. But perhaps the best response came from Cleveland native and  longtime Brownie fan, Drew Carey. On an episode of his hit show shortly after the move, when guest star and former Brown Bernie Kosar asked where the bathroom was, Carey pointed it out, before quickly warning Kosar, “But hey, don’t take a Modell in there.”

longtime Brownie fan, Drew Carey. On an episode of his hit show shortly after the move, when guest star and former Brown Bernie Kosar asked where the bathroom was, Carey pointed it out, before quickly warning Kosar, “But hey, don’t take a Modell in there.”