Mitchell Page

Mitchell Page

One of the most exciting young players that Charlie Finley, the one-time maverick owner of the Oakland A’s, received when selling off one of the last members of his powerful, mustachioed and electric green-and-yellow-wearing, three-time World Champions of the 1970's. A guy whose oh-so promising career seemed to end almost as soon as it started. And a guy who, perhaps surprisingly, later re-surfaced as Albert Pujols’ hitting coach with the Cardinals.

After having traded away Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson for prospects, and having lost free agents Sal Bando, Joe Rudi, Rollie Fingers and Catfish Hunter, without receiving any compensation at all (as well as attempting to sell Rudi, Fingers and Vida Blue to Boston and New York for a combined $3.5 million a year earlier, only to have the deals overturned by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who claimed he was ruling “in the best interests of baseball”), Finley swapped his starting 2B Phil Garner and two garden-variety throw-ins to the Pirates for a five-player haul of minor league talent that included three potential All Stars, Tony Armas, Rick Langford, and perhaps the most talented of them all, Page.

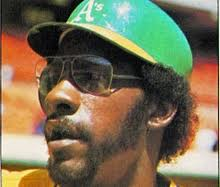

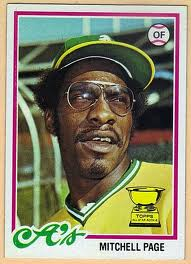

Mitchell Page was a slashing, power-hitting OF from the notorious mean streets of Compton, California – a place which had given rise to some of the most ruthless African-American gangs of the day – and was known for his large aviator glasses and his powerful, almost violent left-handed swing. He also carried with him on the field a real sawgger and a palpable sense of excitement.

Mitchell Page was a slashing, power-hitting OF from the notorious mean streets of Compton, California – a place which had given rise to some of the most ruthless African-American gangs of the day – and was known for his large aviator glasses and his powerful, almost violent left-handed swing. He also carried with him on the field a real sawgger and a palpable sense of excitement.

When he would stroll to the plate that first year in Oakland, A’s announcer Monte Moore would often tell listeners in a dramatic, animated fashion, “Here he comes…Mitchell Page, the Swingin’ Rage.”

He also – according to many players who played with and against him, as well as many he coached, and who coached alongside him – may just have had the deepest speaking voice of any man on the planet.

In 1977, Page’s first year with the A’s, while playing in cavernous Oakland Alameda County Stadium and regularly batting third, he hit a robust .307, with 21 HR, 75 RBI and 42 SB in 47 attempts. For his outstanding '77 campaign, Page received nine first-place votes and finished second overall in the Rookie of the Year balloting behind future Hall of Famer, Eddie Murray; ironically, another kid from the streets of Compton.

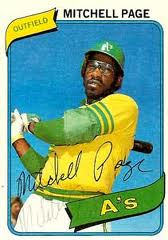

But then it all seemed to unravel for Page. He had a pretty good sophomore season, though his numbers dropped noticeably across the board. Two years later, however, over the course of a full season, he hit an empty .247, with just 9 HR and 42 RBI. It would be Page’s last season as a regular.

But then it all seemed to unravel for Page. He had a pretty good sophomore season, though his numbers dropped noticeably across the board. Two years later, however, over the course of a full season, he hit an empty .247, with just 9 HR and 42 RBI. It would be Page’s last season as a regular.

Perhaps, not coincidentally, some teammates and coaches began noticing around that time that Page had developed a taste for both booze and cigarettes, and was playing as hard off the field as he was on it.

The next five seasons – his last five seasons as a player, in fact – the now part-timer and occasional pinch hitter would average only 137 AB per year, while hitting just .231 and totaling a mere 25 HR. Page was finally released by the last-place Pirates in 1984, after only 12 AB.

In 1998, he was hired by the Cardinals to coach their minor league hitters at AAA Memphis, and in 2001 was named hitting coach of the big club in St. Louis. Among his students that first year was the prodigious Pujols, who under Page would go on to win Rookie of the Year honors and put together one of the most productive starts to any career in Major League Baseball history.

Immediately, however, after the 2004 World Series, during which his Redbirds hit just .190 while being swept by the Boston Red Sox, Page checked himself into a substance-abuse clinic and stepped down as the Cardinals' hitting coach. He would never work regularly in the Major Leagues again.

At the time of his death seven years later, he had been employed as a part-time hitting instructor for St. Louis.

At the time of his death seven years later, he had been employed as a part-time hitting instructor for St. Louis.

Mitchell Page was found dead this past March in a Jupiter, Florida hotel room, not far from the Cardinals’ Spring Training complex. Cause of death was listed as natural causes. He was 59.

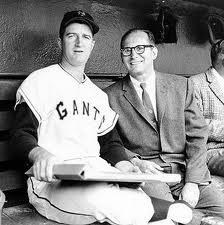

Don Mueller

Don Mueller

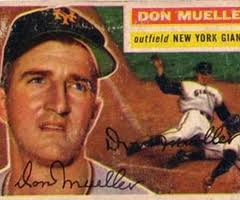

He was, perhaps, the greatest singles hitter of his day, a man they often called “Mandrake the Magician” for his uncanny ability to find holes in the infield and then slap singles through them, and a guy who played a remarkable but largely unsung role in what was probably the single greatest moment in baseball history.

In the bottom of the 9th against the Brooklyn Dodgers in the final game of the 1951 playoff for the N.L. pennant, the Giants found themselves on the short end of a 4-1 score. After an Alvin Dark single to start the inning, Mueller came to the plate with Dodger 1B Gil Hodges playing behind the runner, Dark.

Since Hodges was playing what amounted to a “no-doubles” defense, he was guarding the line and not playing his normal position. Looking out of the corner of his eye at the hole created by a vacated Hodges on the right side of the infield, Mueller slapped a hard-hit grounder just past the Dodger 1B for a clean single to RF, a ground ball that under most circumstances Hodges might have turned into a double play.

Since Hodges was playing what amounted to a “no-doubles” defense, he was guarding the line and not playing his normal position. Looking out of the corner of his eye at the hole created by a vacated Hodges on the right side of the infield, Mueller slapped a hard-hit grounder just past the Dodger 1B for a clean single to RF, a ground ball that under most circumstances Hodges might have turned into a double play.

On the play, Dark turned second sharply and flew into third. And when the next batter, Whitey Lockwood, hit a line drive double into the corner, the Giants suddenly had one run in, with runners on second and third and nobody out.

The following batter, Giant RF Bobby Thompson, was tight as a drum as he moved toward the plate. It was only when he looked down and saw people rushing in the direction of Mueller, his Giant teammate, that he was able to take a moment and collect himself.

The following batter, Giant RF Bobby Thompson, was tight as a drum as he moved toward the plate. It was only when he looked down and saw people rushing in the direction of Mueller, his Giant teammate, that he was able to take a moment and collect himself.

Mueller had slid awkwardly into 3B and injured himself badly on Lockwood’s smash. And, just as years later Thompson would tell sportswriters about his legendary “Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” his thoughts were no longer on the game. They were with his teammate and friend, the slap-hitting two-time All Star who had just been carried off the Polo Grounds infield with a badly broken ankle.

And Thompson contends to this day that it was not the moment or the situation, but Don Mueller’s potential career-ending injury that he was focused on when he stepped in to face reliever Ralph Branca, and it was his thoughts of his fellow Giant OF that allowed him to compose himself just long enough to dig in for what was about to become the most famous AB in major league history.

And Thompson contends to this day that it was not the moment or the situation, but Don Mueller’s potential career-ending injury that he was focused on when he stepped in to face reliever Ralph Branca, and it was his thoughts of his fellow Giant OF that allowed him to compose himself just long enough to dig in for what was about to become the most famous AB in major league history.

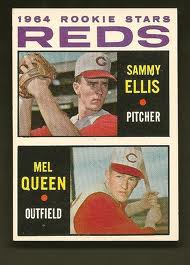

Mel Queen, Jr.

Mel Queen, Jr.

One of a handful of players, who made it to the big leagues as both a pitcher and position player. However, unlike most converted hurlers, Queen both played and pitched in the same year, appearing in 32 games for the 1966 Reds as an OF, while appearing in six games on the mound that very same season.

Queen's greatest baseball legacy, however, came not as a player but as pitching coach for the Toronto Blue Jays. Of the four years in which he served as the Jay’s pitching coach, Pat Hentgen won the A.L. Cy Young Award in 1996, while Roger Clemens won it in both ’97 and ’98.

But even that might not have been his greatest achievement as a coach.

But even that might not have been his greatest achievement as a coach.

In 2001, working as a minor league instructor with 24-year old Roy Halladay, who had gone 4-7 with a 10.64 ERA just a year prior, and who had been demoted all the way from Toronto to Class A Dunedin, Queen changed his arm slot, taught him two new grips on his fastball, and literally, transformed him from a historically failed phenom into not only a Cy Young Award winner but, arguably, the best pitcher of his generation.

A few years earlier, while serving as pitching coach of the Jays in 1999, Queen led a revolt against then-manager Tim Johnson, who Queen learned had lied about being Marine in Viet Nam as a way of motivating his players – including a story about how he once been forced to shoot a young Vietnamese girl. With Queen as Johnson’s most outraged and vocal critic, Johnson was subsequently fired in Spring Training, the first time a manager had gotten the axe that early in a season since Cub owner Philip K. Wrigley canned Phil Cavaretta prior to the ’54 campaign.

Queen, whose father was an OF with the Yankees and Pirates back in the late 40’s and early 50’s, had his finest year as a player in 1967 – his first year as a full-time pitcher – when he went 14-8 with a 2.76 ERA for Cincinnati, while twirling two complete game shutouts for the Reds.

Queen, whose father was an OF with the Yankees and Pirates back in the late 40’s and early 50’s, had his finest year as a player in 1967 – his first year as a full-time pitcher – when he went 14-8 with a 2.76 ERA for Cincinnati, while twirling two complete game shutouts for the Reds.

In parts of seven seasons with the Red and Angels he would compile a lifetime ERA of 3.14.

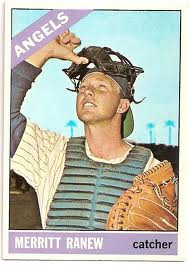

Merritt Ranew

Merritt Ranew

In one sense, he was just one more journeyman catcher floating in that ill-defined gap between AAA and the big leagues. But in another he was a remarkable competitor and a fiercely loyal teammate; a little like the fictional Bruce Pearson, the hard-working, but not-so-talented receiver in Mark Harris' novel, Bang the Drum Slowly, a simple man and a trusty footsoldier whose guts, passion and heart always seemed to offset whatever shortcomings he may have had as a player.

One time, while catching for the Seattle Angels of the PCL against the Vancouver Mounties, Ranew came to the defense of his pitcher and it nearly cost him his life. It was the spring of 1966, just a few months after the Giants' Juan Marichal had shocked the baseball world by beating Johnny Roseboro bloody with a number of vicious and potentially lethal swings of his bat to Dodger catcher's head.

Sports Illustrated described the incident involving Ranew, which took place in Vancouver in May of that year:

Sports Illustrated described the incident involving Ranew, which took place in Vancouver in May of that year:

Seattle Pitcher Jim Coates threw one high and tight and struck Ricardo Joseph of Vancouver on the shoulder. Joseph charged the mound, but before he could get to Coates, he was tackled from behind and had his chin bloodied by Seattle catcher Merritt Ranew.

The ensuing free-for-all finally subsided, but then Vancouver’s Tommy Reynolds bunted up the first base line, forcing Coates to field the ball and tried to run the pitcher down. Again Ranew raced to the aid of Coates. Vancouver’s Santiago Rosario dashed from the on-deck circle and hit Ranew over the head with his bat, opening up a deep, three-inch gash. There is internal bleeding in the brain, and the left side of Ranew’s face is paralyzed.

It can be said now that Merritt Ranew drifted near death for days after the attack, with a blood clot on the brain that had to be removed surgically in what doctors told him later was a life-or-death operation. He didn't regain consciousness until nearly 72 hours after the procedure, and remained hospitalized for a full three weeks after the incident.

It can be said now that Merritt Ranew drifted near death for days after the attack, with a blood clot on the brain that had to be removed surgically in what doctors told him later was a life-or-death operation. He didn't regain consciousness until nearly 72 hours after the procedure, and remained hospitalized for a full three weeks after the incident.

Though he later professed a lack of respect for Rosario, and admitted the doctors told him after he woke up following the operation it could have gone either way, he found a way to put it all behind him. Ranew was back next Spring Training behind the plate, again in the minor leagues, again catching in Seattle, and again trying to do whatever it took to get himself to the big leagues.

Merritt Ranew never did achieve much of a Major League career, but he does have this distinction: he remains the only man who ever wore the uniforms of both the shortest-lived teams in modern baseball history. He was a member of the Houston Colt 45's for one of the three years the National League expansion team played under that name, and a member of the legendary '69 Seattle Pilots during that storied club's only year of existence.

After baseball, Ranew returned home to Albany, Georgia where he became a successful businesman, trained and rode a number of prize-winning show horses, including one World Champion, humbly accepted the key to his hometown, and accoring to some who knew him, rarely ever talked about his baseball career.

After baseball, Ranew returned home to Albany, Georgia where he became a successful businesman, trained and rode a number of prize-winning show horses, including one World Champion, humbly accepted the key to his hometown, and accoring to some who knew him, rarely ever talked about his baseball career.

In fact, it was not until Steven Lee, Ranew's step-son, read about the Santigo Rosario incident online a few months back -- even as the former gutsy catcher lay near death in a nearby hospice -- that he learned of the tragedy that almost befell his step-father on that near-fateful night in Vancouver so many seasons ago.

Shannon Stone

Shannon Stone

When Shannon Stone was 12 years old he went to a Texas Rangers game. He especially wanted to see his favorite Ranger, Buddy Bell. He brought his glove, just in case. Shannon’s dream was to catch a foul ball hit by Buddy Bell.

Sure enough, at one point that day Bell lifted a ball into the stands. At first, it looked well short of where Shannon was, but then a gust of wind caught the ball and carried it closer and closer to him, until using his glove he reached up and caught it clean.

It was, at that point in his young life, Shannon Stone’s greatest moment ever, and one he would never forget.

This past summer, the Dallas-area fireman wanted to take six-year old Cooper Stone to a Ranger game. So the night before, the two went out and bought Cooper a glove. His father talked about his catching Bell’s foul ball, and asked his son who his favorite Ranger was, and told him maybe he’d catch one of his foul balls.

This past summer, the Dallas-area fireman wanted to take six-year old Cooper Stone to a Ranger game. So the night before, the two went out and bought Cooper a glove. His father talked about his catching Bell’s foul ball, and asked his son who his favorite Ranger was, and told him maybe he’d catch one of his foul balls.

Cooper said it was Josh Hamilton, so his father also bought him a Hamilton jersey.

By now, we all know the sad, tragic story. The next day, hoping to get a ball for Cooper, Shannon yelled to Hamilton between innings, who tossed him a ball as he stood in the front row of the stands. Hamilton motioned to Shannon, and then seemed to purposefully underthrow the ball so only he would be able to grab it.

Straining forward ever-so-slightly to catch the ball, Stone suddenly tumbled out of the stands and onto the hard concrete of the Oakland A’s bullpen, some 20’ below. A’s pitcher Brad Ziegler, who was in the visitor’s bullpen, watched in horror. He could see Shannon’s arms were broken and saw the blood flowing from his head.

Straining forward ever-so-slightly to catch the ball, Stone suddenly tumbled out of the stands and onto the hard concrete of the Oakland A’s bullpen, some 20’ below. A’s pitcher Brad Ziegler, who was in the visitor’s bullpen, watched in horror. He could see Shannon’s arms were broken and saw the blood flowing from his head.

When Zeigler and others rushed to his aid, Stone, who had suffered a brain injury, kept trying to stay awake so he could tell people to take care of Cooper. The last words Shannon would say just before lapsing into unconsciousness were to a fire lieutenant on the scene. Stone told his fellow firefighter, “My son is up there. Please check on my son.”

A few days after Stone’s death, and amid much hue and cry for players to stop tossing balls into stands, SuZann Stone sent a hand-written letter to Josh Hamilton. She said he should not for a minute believe he had anything to do with her son’s death, that it was an accident, and that he should continue to throw baseballs to fans, especially young ones.

A few days after Stone’s death, and amid much hue and cry for players to stop tossing balls into stands, SuZann Stone sent a hand-written letter to Josh Hamilton. She said he should not for a minute believe he had anything to do with her son’s death, that it was an accident, and that he should continue to throw baseballs to fans, especially young ones.

“That’s why fathers and sons go to baseball games,” she wrote the Ranger star.

“That’s why fathers and sons go to baseball games,” she wrote the Ranger star.

There seems to be no end of victims in this tragedy; Shannon Stone, certainly, as well as his 36-year old widow and loving, understanding mother. Even Hamilton, a stunningly talented player who has battled drug and alcohol addiction for years, and whose demons remain so strong and so prevalent in his life that the Rangers give him a 24-hour handler to help him resist temptation, whenever it may occur.

But, perhaps, the biggest victim of all is Cooper Stone, a six-year old boy who this past summer watched his father die doing something he loved; a simple act fathers all across America would hope, given the chance, to be able to do for their kids – catch them a foul ball.

But, perhaps, the biggest victim of all is Cooper Stone, a six-year old boy who this past summer watched his father die doing something he loved; a simple act fathers all across America would hope, given the chance, to be able to do for their kids – catch them a foul ball.

We can only hope that in time Cooper will find it in him to see, as his grandmother does, that what killed his father was an accident, and that his father died not only doing something he loved, but doing it with someone he loved.

And what’s more, as he showed by his willingness to share his passion for baseball with his son, his joy at teaching his son about the game, and his desire to protect Cooper even as death was closing in, Shannon Stone proved to be more father in six years than a lot of men prove to be in a lifetime.

And what’s more, as he showed by his willingness to share his passion for baseball with his son, his joy at teaching his son about the game, and his desire to protect Cooper even as death was closing in, Shannon Stone proved to be more father in six years than a lot of men prove to be in a lifetime.

Roy Smalley, Jr.

Roy Smalley, Jr.

Arguably, one of the worst fielders in the history of Major League Baseball and the father of longtime Minnesota Twins SS, Roy Smalley III.

Playing for the Cubs in the late 40's and early 50's, Smalley became known as a real butcher at SS by many local fans and sportswriters. In 1950, despite achieving career highs in both HR (28) and RBI (85), Smalley led the league with an astounding 51 errors. In fact, he remains the last player, regardless of position, to commit more than 50 errors in a season.

He also struck out a league-leading 114 times that year.

That year was also memorable for Smalley in one other way. In 1950, he married Jolene Mauch, a pretty young girl whose older brother, Gene, was Smalley's teammate on the Cubs. The couple's son, Roy III, would grow up to play for Gene Mauch, who after he retired would go on to manage a number of teams, including young Roy's team, the Twins.

That year was also memorable for Smalley in one other way. In 1950, he married Jolene Mauch, a pretty young girl whose older brother, Gene, was Smalley's teammate on the Cubs. The couple's son, Roy III, would grow up to play for Gene Mauch, who after he retired would go on to manage a number of teams, including young Roy's team, the Twins.

For what it's worth, the day of his wedding to Jolene, Smalley played against the Boston Braves. He went 0-5.

Smalley also earned a place in Cub lore for two other items. Not only was he the player that Mr. Cub, two-time MVP, and future Hall of Famer, Ernie Banks, would eventually replace at SS for the Cubs, but he and one-time keystone partner, Eddie Miksis (himself someting of a butcher with the glove) earned a tongue-in-cheek lyrical tribute for their collective fielding misadventures. It was a lyric based on an earlier, far more proficient and far more storied Chicago Cub infield combination.

Only in their case, the words didn't read "Tinker to Evers to Chance." They read "Smalley to Miksis to Addison."

Only in their case, the words didn't read "Tinker to Evers to Chance." They read "Smalley to Miksis to Addison."

Addison, of course, is the street that runs just outside of Wrigley Field.

Duke Snider

Duke Snider

A Hall of Fame player who found himself overshadowed by – but who eventually benefitted from – the other two great Hall of Fame CF in the New York of the 1950’s.

Snider was one of the legendary “Boys of Summer” and was known to millions as the “Duke of Flatbush” while playing for the storied Brooklyn Dodgers of that era. And he hit 40+ HR for five consecutive seasons, including 1955 when ”dem Bums” finally won their one and only World Series.

But he was never going to be as talented or as powerful as Yankee legend, Mickey Mantle, or as electrifying and as jaw-dropping or as dramatic as the Giants’ immortal, Willie Mays.

In time, however – particularly after New York born-and-raised songsmith, Terry Cashman, wrote and recorded his paean to America’s pastime, Talkin’ Baseball, which he built around the insidiously catchy and wonderfully poetic phrase, “Willie, Mickey and the Duke” – Snider found himself immortalized to a whole new generation of fans as a member of some sort of Holy Trinity of CF; three baseball legends who played during the glory days of Jack Dempsey’s, Toots Shor’s, and a town whose brash, loud, confidence in retrospect might have led one to believe that the whole world – socially, culturally and, in particular, sporting-wise – revolved around the City of New York.

In time, however – particularly after New York born-and-raised songsmith, Terry Cashman, wrote and recorded his paean to America’s pastime, Talkin’ Baseball, which he built around the insidiously catchy and wonderfully poetic phrase, “Willie, Mickey and the Duke” – Snider found himself immortalized to a whole new generation of fans as a member of some sort of Holy Trinity of CF; three baseball legends who played during the glory days of Jack Dempsey’s, Toots Shor’s, and a town whose brash, loud, confidence in retrospect might have led one to believe that the whole world – socially, culturally and, in particular, sporting-wise – revolved around the City of New York.

Which, I guess if you were a baseball fan, it did. And a big part of that fact was tied to Snider and fellow Boys of Summer, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Gil Hodges and Pee Wee Reese; great guys on a great team who always seemed to come up short – at least, that is, until the magical summer of ‘55.

Which, I guess if you were a baseball fan, it did. And a big part of that fact was tied to Snider and fellow Boys of Summer, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Gil Hodges and Pee Wee Reese; great guys on a great team who always seemed to come up short – at least, that is, until the magical summer of ‘55.

The Dodgers’ first year in Los Angeles, with its cavernous Coliseum serving as a temporary holding tank, was not particularly kind to the aging slugger, and a few years later the Duke found himself bouncing around the league until, like so many other ex- New York greats, he looked around one morning and found himself smack dab in the middle of a circus known as the New York Mets. Realizing he was not so much on a team, as he was part of a sideshow – and that he was doing little more than help sell tickets for ringmaster Casey Stengel – he respectfully retired shortly after a trade to the dreaded Giants with both his legacy and dignity intact.

Snider later brought his soft-spoken, laid-back style to the broadcast booth, and for 14 years teamed with the legendary Montreal Expo play-by-play man, Dave Van Horne, himself a Hall of Famer. Together, the smooth, polished and often animated Van Horne and the soft-spoken but always candid Snider comprised one of the great local broadcast teams in modern baseball history.

Snider later brought his soft-spoken, laid-back style to the broadcast booth, and for 14 years teamed with the legendary Montreal Expo play-by-play man, Dave Van Horne, himself a Hall of Famer. Together, the smooth, polished and often animated Van Horne and the soft-spoken but always candid Snider comprised one of the great local broadcast teams in modern baseball history.

Following his retirement from broadcasting, one could occasionally catch Snider at a baseball function, where he’d every so often start to rail about the modern ballplayer and his big money, his unwillingness to play hurt, and his often cavalier attitude toward the game the Duke loved so deeply.

Following his retirement from broadcasting, one could occasionally catch Snider at a baseball function, where he’d every so often start to rail about the modern ballplayer and his big money, his unwillingness to play hurt, and his often cavalier attitude toward the game the Duke loved so deeply.

But just as quickly as he started, he’d catch himself, smile and move on.

It was almost as though the old Brooklyn Dodger suddenly remembered that not every ballplayer was as blessed as Duke Snider was, and that very few men in this world were lucky enough to have played, not only where he did, but when he did.

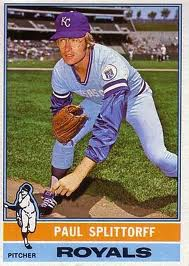

Paul Splittorff

Paul Splittorff

A guy who in 1968 threw the first pitch in the history of the Kansas City Royals’ organization while twirling for the club’s Class A affiliate in Corning (NY), a full year before the Major League team would actually be drafted and take the field, and a steely competitor who would go on to win more games than any pitcher in club history.

During their three classic mid-70’s ALCS matchups, if George Brett was Kansas City’s “Yankee-killer” on offense, his pitching counterpart was Splittorff, a big, bespectacled lefty, whose tall, solid frame, broad shoulders and high-leg kick belied a repertoire that relied more on movement, timing and location than actual power.

But the relentlessly stoic Splittorff was as mentally tough as any pitcher on the staff, and in those three series found a way to crawl inside the Yankees’ head and seemed to psyche them out in a way many far more talented pitchers never did.

Looking more like an accountant than a Major Leaguer, Splittorff’s tailing fastball often had right-hand hitting Yankees beating balls into the dirt, while lefties often found themselves tied up inside.

Looking more like an accountant than a Major Leaguer, Splittorff’s tailing fastball often had right-hand hitting Yankees beating balls into the dirt, while lefties often found themselves tied up inside.

In fact, Splittorff so utterly confusd certain Yankee hitters that in the deciding game of the '77 ALCS, with the crafty Royal lefty scheduled to pitch, New York manager Billy Martin opted not to start his Hall of Famer RF, Reggie Jackson, because in Martin's words, "he can't hit Splittorff."

For his career, covering a total of four post-season series against New York, Splittorff was 2-0, with a sparkling 2.86 ERA. The reason he didn’t win more games is that Yankee offense often got healthy and rallied against the Royal bullpen, curiously, many times almost as soon as Splittorff had departed.

Following his playing days, Splittorff retired to a career as color man on the Royals’ television broadcasts. Unfortunately, unless you were weaned on the lefty’s dry, monotone delivery and a speech pattern conspicuously devoid of inflections, you probably found him boring.

Following his playing days, Splittorff retired to a career as color man on the Royals’ television broadcasts. Unfortunately, unless you were weaned on the lefty’s dry, monotone delivery and a speech pattern conspicuously devoid of inflections, you probably found him boring.

It was almost as though what made him an effective pitcher; namely, never tipping his hand, never showing emotion and always playing his cards close to his vest, seemed to hinder him as a broadcaster.

Nevertheless, he was deeply loved by the Kansas City faithful and when he passed earlier this summer from a combination of melanoma and oral cancer, he was mourned widely, and the Royals players honored him with a black circular patch that, much in keeping with his minimalistic, unadorned style, read simply, “Splitt.”

Splittorff, interestingly enough, holds the distinction of being the pitcher who has won the most games in the history of baseball without ever making the All Star game (166).

Splittorff, interestingly enough, holds the distinction of being the pitcher who has won the most games in the history of baseball without ever making the All Star game (166).

In addition, despite going 14-10 for the 1980 American League Champion Royals, he found himself passed over by manager Jim Frey, who chose not to give him a start in that year’s World Series, which Kansas City went on to lose to Philadelphia, 4-2.

It was one of the few times in his public life that Splittorff ever showed any real emotion, and those who knew him best say he never forgot what Frey had done to him.

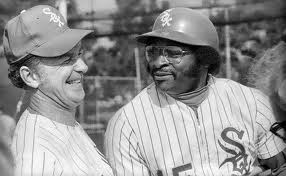

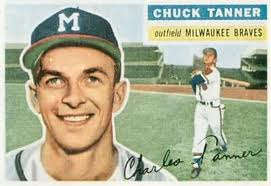

Chuck Tanner

Chuck Tanner

One of the most positive, upbeat and hands-off managers in Major League history; a guy in the corner office who let the players play, gave them plenty of encouragement, and tried to interfere in their lives and the game as little as humanly possible.

When his infectious brand of optimism and almost utter lack of rules actually worked, such as with the chain-smoking and horse-betting Dick Allen (who often showed up for games just before first pitch) and his surprising White Sox who fought the powerful A’s of Reggie Jackson, Catfish Hunter, Joe Rudi and Sal Bando tooth-and-nail right up to the final days of the '72 season, the results could be magic.

When his infectious brand of optimism and almost utter lack of rules actually worked, such as with the chain-smoking and horse-betting Dick Allen (who often showed up for games just before first pitch) and his surprising White Sox who fought the powerful A’s of Reggie Jackson, Catfish Hunter, Joe Rudi and Sal Bando tooth-and-nail right up to the final days of the '72 season, the results could be magic.

But when it didn’t, such as with Tanner’s wildly undisciplined and horribly underachieving Pirates of the early 80’s, a team which had players abusing, even trafficking cocaine in the clubhouse, the results could be downright cancerous.

Perhaps the greatest example of Tanner’s hands-off approach working, as he always hoped it would, was in Pittsburgh in 1979.

Perhaps the greatest example of Tanner’s hands-off approach working, as he always hoped it would, was in Pittsburgh in 1979.

That season, the Bucs of We Are Family fame, who were an exciting mix of both young and veteran players, took their lead, not from Tanner, but from the future Hall of Famer and clubhouse father figure, Willie “Pops” Stargell.

The Pirates of that year rode Stargell's experience, wisdom, strong will and remarkably gentle and calming presence to a stunning comeback win over the Orioles in a hotly contested, seven-game World Series.

And all season long, Tanner appeared more cheerleader than manager, and regularly left such things as discipline, instruction, motivation, even post-game press comments, up to Stargell.

As far as his legacy goes, very few people remember that in 1972 it was Tanner who turned young flame-throwing starting pitcher Rich Gossage into his closer, a move that would eventually put the hard-throwing right-hander on a path to the Hall of Fame.

For that and other moves, including keeping his over-achieving White Sox in a pennant race all summer long, the Sporting News named the enormously popular Tanner the A.L. Manager of the Year. Meanwhile, his best player, Allen, the slugging first baseman Tanner let come and go as he pleased, took home MVP honors.

For that and other moves, including keeping his over-achieving White Sox in a pennant race all summer long, the Sporting News named the enormously popular Tanner the A.L. Manager of the Year. Meanwhile, his best player, Allen, the slugging first baseman Tanner let come and go as he pleased, took home MVP honors.

Tanner’s other achievement of note was that he is one the few managers in history ever traded for a player, moving to Pittsburgh in 1977 from the Oakland A’s in exchange for catcher Manny Sanguillen.

The eternally positive New Castle, Pennsylvania native managed nearly a decade after his memorable World Championship in '79, before retiring following an abysmal two-year run with the then-aging and pitching-poor Atlanta Braves, who canned Tanner following a 12-28 start to the '88 season.

The eternally positive New Castle, Pennsylvania native managed nearly a decade after his memorable World Championship in '79, before retiring following an abysmal two-year run with the then-aging and pitching-poor Atlanta Braves, who canned Tanner following a 12-28 start to the '88 season.

When Tanner finally decided to call it quits, go home and flip burgers at his New Castle restaruant, he took with him his still-rosy outlook, his still-positive attitude and a lifetime mark of 1,352 – 1,381

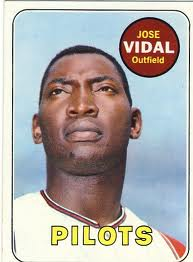

Jose Vidal

A guy for whom the DH came around just a decade or so too late, and a guy for whom the term "journeyman" could have been coined, having kicked around over dozen cities for 14 seasons.

Vidal was a pretty good-hitting and gregarious, even animated OF from the Dominican Republic who, sadly, could not field a lick. He led his minor league in OF errors three times in the course of seven seasons.

Vidal was a pretty good-hitting and gregarious, even animated OF from the Dominican Republic who, sadly, could not field a lick. He led his minor league in OF errors three times in the course of seven seasons.

Jose Vidal began his very brief and very spotty Major League career in '66 with a triple for the Indians and ended it in '69 with a triple for the Seattle Pilots.

In between, he achieved his personal Kodak moment in June of 1968, when on the 3rd of that month he hit a 14th-inning walk-off HR off Jack Fisher that pushed Cleveland past the White Sox and gave lifelong journeyman Hal Kurtz the only victory of his brief and spotty career.

In parts of four big league seasons, Jose Vidal managed to amass lifetime totals of just 3 HR and 10 RBI, to go along with a BA of .164.

And for what it's worth, Kurtz, Vidal's one-time teammate and fellow minor league journeyman -- perhaps aware that he, like Vidal, was doing it with smoke and mirrors -- had taken time earlier that spring to publicly declare that he was shocked to have won a spot on the Tribe's staff, and thanked manager Alvin Dark in the press for the opportunity.

And for what it's worth, Kurtz, Vidal's one-time teammate and fellow minor league journeyman -- perhaps aware that he, like Vidal, was doing it with smoke and mirrors -- had taken time earlier that spring to publicly declare that he was shocked to have won a spot on the Tribe's staff, and thanked manager Alvin Dark in the press for the opportunity.

Then, no doubt reading the tea leaves far better than Vidal as to what the future held, he walked away from the game just a few months after that memorable night in Cleveland, leaving his career record a spotless, 1-0.

Dick Williams

Dick Williams

A Hall of Fame manager who is one of only seven men to win a pennant in both leagues and one of only two men to take three different clubs to the World Series, an outspoken strategist who sparred openly with owner Charlie Finley while leading the Swingin’ A’s to the first two of three consecutive World Championships in the 1970’s, and a guy who as a first-year manager took the unlikely “Impossible Dream” Red Sox of '67 from 9th place the year before to one win away from a World Series title.

When he was named Sox manager the winter before the ’67 season, Williams had never managed before in the big leagues. And at the time, neither he nor the Sox were very highly regarded by the national baseball media. The Sox had been bottom-feeders eight seasons in a row, and just two years prior had dropped 100 games.

But Williams came up from Boston's AAA affiliate in Toronto with a reputation for being a stern task-master who demanded fundamentals and who was a stickler for conditioning. One of the first things he did was call the Sox All Star 1B George “Boomer” Scott “fat” – which, truth be told, he was.

By the middle of the year, led by Carl Yastrzemski (who would go on to win the Triple Crown and be named MVP) and pitcher Jim Lonborg (who would capture the Cy Young Award), the now suddenly well-drilled and well-conditioned Sox were right in the thick of things, and were clearly not going away. Soon, what had been a New England baseball fanbase sleepwalking through one losing season after another started going crazy.

By the middle of the year, led by Carl Yastrzemski (who would go on to win the Triple Crown and be named MVP) and pitcher Jim Lonborg (who would capture the Cy Young Award), the now suddenly well-drilled and well-conditioned Sox were right in the thick of things, and were clearly not going away. Soon, what had been a New England baseball fanbase sleepwalking through one losing season after another started going crazy.

And when the Sox won the pennant on the final day of the season, nosing out three other teams in a historically close race that saw four clubs divided by just one game with only three days to go, Williams was declared a genius and a baseball savior throughout New England.

In fact, current Sox announcer and lifelong fan, Jerry Remy, contends to this day that Williams’ team was the start of the baseball mania in Fenway as we now know it. Said Remy, “That ’67 team created the ‘Red Sox Nation’ we know today. They truly re-invented baseball in New England."

After Boston, Williams moved to Oakland, where the year prior the A’s had made a move toward being a championship team, but had yet to get over the top. Again stressing fundamentals and conditioning, Williams came in and pushed and cajoled the A’s budding superstars into testing the upper limits of the abilities as players. And when things clicked, and the A’s realized how good they could be, the Bay Area found itself with the first dynasty baseball had seen since the powerful Yankees of the late 50’s and early 60’s.

After Boston, Williams moved to Oakland, where the year prior the A’s had made a move toward being a championship team, but had yet to get over the top. Again stressing fundamentals and conditioning, Williams came in and pushed and cajoled the A’s budding superstars into testing the upper limits of the abilities as players. And when things clicked, and the A’s realized how good they could be, the Bay Area found itself with the first dynasty baseball had seen since the powerful Yankees of the late 50’s and early 60’s.

But even as they were winning, the sharp-tongued Williams constantly clashed with Finley, a horrific meddler and notorious skinflint. And when Finley publically humiliated reserve 2B Mike Andrews – a player signed by Williams, over Finley’s objections, because he was such a key part of the Red Sox’ success in ‘67 – by first “firing” him during the World Series, then forcing him to sign an affidavit saying he was injured so Finley could replace him, a disgusted Williams used the owner's bullying tactics to unite the team and motivate them to win the Series. He then immediately resigned as manager of the A’s.

In the National League, his two greatest managing jobs were with two expansion teams who came into being in 1969, the Montreal Expos and the San Diego Padres.

In the National League, his two greatest managing jobs were with two expansion teams who came into being in 1969, the Montreal Expos and the San Diego Padres.

With Montreal, Williams took budding stars Gary Carter, Andre Dawson, Larry Parrish and Steve Rogers and molded them into a perennial contender, finishing second in the N.L. East to two eventual World Champions, the 1979 Pirates and the 1980 Phillies.

But when he challenged Rogers openly in the press, and questioned his toughness in big games, he started to lose the team for his willingness to go public with such thoughts. Williams was fired with just weeks to go in the strike-shortened ’81 season, and it was interim manager Jim Fanning who led the Expos into their first-ever post-season.

Williams’ tenure with the Padres, who he led into their very first post-season, was marked by two items of note.

He was San Diego’s skipper in the '84 NLCS when one of the most infamous plays in Chicago Cub history unfolded, as Tim Flannery’s two-out grounder trickled under Leon Durham’s glove and turned a sure Cub trip to their first World Series in nearly 40 years into even more pain and suffering, while sending the Padres to their first-ever.

Then, during that very same post-season (and as captured magnificently by MLB’s camera crew) late in the final game of the Series, Williams was talked out of a key piece of strategy by one of his players, and it cost him dearly.

Rather than walking the Tigers’ Kirk Gibson, as both the book and Williams called for, reliever Rich Gossage convinced his manager that he could strike out Gibson. So instead of giving the slugger an intentional pass, Williams let Gossage pitch to Gibson, who then proceeded to turn on a belt-high fastball and drive it deep into the Tiger Stadium stands to win the game and clinch the Series.

Williams, who played for seven teams in his big league career, and managed six, would retire four years just later with a 1,571 – 1,461 record.

Williams, who played for seven teams in his big league career, and managed six, would retire four years just later with a 1,571 – 1,461 record.

Outspoken and highly respected right to the very end, Williams was named to the Baseball Hall of Fame by its Veterans Selection Committee in 2008.

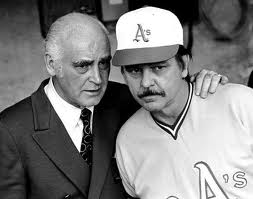

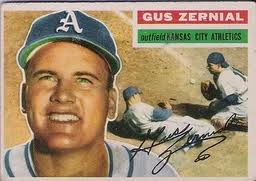

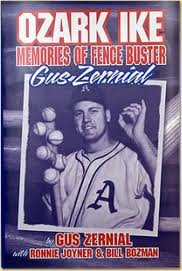

Gus Zernial

Gus Zernial

To some, Zernial was the powerful, giant of a man some reporter along the way decided to call “Ozark Ike,” or the strapping Texan who in 1950 the White Sox swapped to the A's to land future icon, Minnie Minoso.

To others, he was the hitter who hit more HR between '50-'57 than any player in the A.L., including Mickey Mantle, Ted Williams, Al Rosen and Yogi Berra.

And to those geeks who love baseball esoterica, he was – at least, that is, until Todd Zeile broke his record eight years ago – the player with the most HR in baseball history with a last name beginning with the letter “Z.”

But make no mistake; who Gus Zernial was, was a guy to whom baseball gave a wonderful life as a young man, and a guy who decades later -- and in desparate need of salvation -- would find that salvation in very same the game he'd fallen in love with as a kid.

But make no mistake; who Gus Zernial was, was a guy to whom baseball gave a wonderful life as a young man, and a guy who decades later -- and in desparate need of salvation -- would find that salvation in very same the game he'd fallen in love with as a kid.

Growing up in Beaumont, Texas, Zernial played baseball from sunup to sundown and got good enough to eventually earn himself a contact from the Cardinals as a teenager.

After returning from World War II, where he did combat duty in the Pacific, he was able to harness his prodigious power and turn it into a Major League career. Along the way he somehow became one of the most feared sluggers of his day – if, indeed, it was possible to actually fear a man as warm, genial and funny as Gus Zernial, a guy who wore a smile like a badge of honor and a guy who seemed to have a amusing story or a good word for anyone who ever needed it.

After returning from World War II, where he did combat duty in the Pacific, he was able to harness his prodigious power and turn it into a Major League career. Along the way he somehow became one of the most feared sluggers of his day – if, indeed, it was possible to actually fear a man as warm, genial and funny as Gus Zernial, a guy who wore a smile like a badge of honor and a guy who seemed to have a amusing story or a good word for anyone who ever needed it.

In fact, as a player Zernial was regarded as so good in his early days with the A's that some around baseball actually started calling him "the next DiMaggio.”

But Gus Zernial was remarkably self-effacing as well. Fully aware he was horribly slow afoot, and a plodding, marginal fielder at best, he loved to make jokes at his own expense, like telling about the time his manager applied the RF shift against Mickey Mantle, leaving Zernial to man 3B, the only guy on the left side of the entire field.

When Mantle tried to cross up the strategy and bunt, and did so directly at Zernial, the big Texan immediately picked up the ball and threw it to 2B. The manager was incredulous and asked Zernial what the hell he was thinking. All the big guy could say was, "Hey skip, I just didn't want him to get a double."

When Mantle tried to cross up the strategy and bunt, and did so directly at Zernial, the big Texan immediately picked up the ball and threw it to 2B. The manager was incredulous and asked Zernial what the hell he was thinking. All the big guy could say was, "Hey skip, I just didn't want him to get a double."

But after a great run for the Sox and A’s that included a bunch of HR, a few All Star game selections, a fair number of MVP votes, and a ton of funny stories, there was a broken collarbone, followed quickly by another. And before he knew what had happened, Gus Zernial’s once-prodigious power was gone, followed soon by his career.

I’ll spare you most of the gory details, but Zernial ended up lost without baseball. In his adopted hometown of Fresno, he tried selling cars for a living. He tried banking. He tried real estate. He tried collections. He tried fund-raising. He tried advertising. He tried sports announcing. He even went back to selling cars. Nothing worked. Not really, anyway.

Zernial never found anything he loved like he loved baseball, and the more he tried to do things he didn’t love, the worse he found he did them.

Eventually he began to think of himself as a failure. He hated his life. He hated his choices. And most of all, he hated doing anything he didn't do as well as he once hit a baseball.

As he told the Fresno Bee years later, he used to drive up and down the highway screaming at the top of his lungs because he hated his job and felt so unfulfilled.

As he told the Fresno Bee years later, he used to drive up and down the highway screaming at the top of his lungs because he hated his job and felt so unfulfilled.

Zernial recalled once getting a call for a broadcasting job with the Chicago White Sox. It was the mid-70’s. But his audition was a painfully bad experience and during it he was, in his words, “cut to ribbons” by a famous announcer, who he refused to name. Zernial went home devastated, more convinced than ever that he had lost baseball for good.

Then in the 80's, Gus tried his hand at financial planning. It was going well for a while, but then the recession hit and suddenly he lost everything he had, not to mention much of what his clients had invested with him. He had truly hit rock bottom, and was now beyond consolation.

In fact, to those who knew him best, the giant of a man and one-time feared slugger even began to physically look smaller.

Zernial constantly asked himself, why hadn’t he pursued announcing with greater conviction as a young man? Why hadn’t he used his name to try to go into coaching or managing? And why had he so utterly turned his back on baseball?

He would run into former fans, and on more than one occasion discovered that people had heard so little about him over the years that a few were under the impression he had died.

He would run into former fans, and on more than one occasion discovered that people had heard so little about him over the years that a few were under the impression he had died.

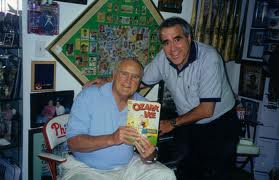

But then in 1990, broke, unfulfilled and still desperately looking for a place to fit in, he read about a local developer trying to build a new state-of-the-art baseball stadium in downtown Fresno, and to lure a AAA team to fill it. Zernial immediately raced down to the guy’s office, burst in, reached out his big hand and said, “My name’s Gus Zernial. I’m going to work for you. Where’s my desk?”

The guy pointed to a table and a phone and said basically, “Have at it.”

What happened next was something out of a Frank Capra movie. Doors that had never been opened before started swinging open because of Gus Zernial's name.

Locals who had never before been interested in bringing baseball to Fresno before, suddenly became very interested in pitching in and doing whatever they could do to help.

And the entire stadium project gained a momentum it might not have otherwise ever achieved without Big Gus' name, not to mention his time, presence and seemingly boundless enthusiasm.

Eventually the stadium was built, the team was formed, and baseball made its way, not just back to Fresno, but back into Gus Zernial’s life. And for the first time since his playing days, he felt he was someplace where he truly belonged.

Eventually the stadium was built, the team was formed, and baseball made its way, not just back to Fresno, but back into Gus Zernial’s life. And for the first time since his playing days, he felt he was someplace where he truly belonged.

As the wife of the developer would say later, “We simply wouldn’t have had that stadium built without Gus.”

Zernial was eventually named the head of community relations for the Fresno Grizzlies and began working as an analyst on their radio broadcasts. He would eventually retire. But unable to stay away, would subsequently find himself back with the Grizzlies, this time as an official “ambassador” to fans during home games.

As longtime Fresno Bee reporter Jeff Smith, who interviewed Zernial in both good times and bad, and with whom the big man had always seemed to be brutally candid about his life, wrote this in an item following Big Gus' passing this past January:

What I'll always remember is Gus standing on the concourse at Chukchansi Park before games surrounded by kids asking for autographs. I'm sure they didn't know anything about his baseball history, or maybe scraps from their parents. But they could tell this huge man was special, not just because of his size but because people sought him out and listened to what he had to say.

Zernial had a lot to say in his life. Most of it true, and some of it painfully so. And so, so much of it funny.

For whatever reason, baseball just seemed to forget Gus Zernial over the years, almost as though he was some sort of journeyman, instead of what he was, one of the greatest sluggers, most indelibe characters and nicest men the game has ever known.

For whatever reason, baseball just seemed to forget Gus Zernial over the years, almost as though he was some sort of journeyman, instead of what he was, one of the greatest sluggers, most indelibe characters and nicest men the game has ever known.

But Big Gus never forgot baseball. And when he needed it most, it was there for him. And in no small way, it helped save his life.

The nice thing, of course, is -- just as so many young fans in Fresno, California will attest, some even without knowing why -- just when baseball needed him most, Gus was there for it too.

Part One of Three: more 2011 baseball deaths you may have missed.

Part Two of Three: more 2011 baseball deaths you may have missed.