It’s funny how so often we fail to appreciate greatness when it’s standing right in front of us, while at other times cling so stubbornly to what is clearly no longer great and insist upon calling it such.

It’s funny how so often we fail to appreciate greatness when it’s standing right in front of us, while at other times cling so stubbornly to what is clearly no longer great and insist upon calling it such.

I’ll go to my grave, for example, contending that if you were to remove the remarkable Michael Corleone and the three endearing sad sacks he played in Dog Day Afternoon, Scarecrow and Donnie Brasco from Al Pacino’s canon of roles, what you’d have left is a body of work that at times can be downright sophomoric to the point of being – especially lately – laughably bad.

And while a young Robert De Niro was utterly stunning in such films as Godfather II, The Deer Hunter and Taxi Driver, and the middle aged De Niro thoroughly entertaining in well-acted and sneaky-smart little comedies like Midnight Run and The King of Comedy, it’s been years since he’s done anything to merit the volumes of lofty praise that somehow still get attached to his name.

And while a young Robert De Niro was utterly stunning in such films as Godfather II, The Deer Hunter and Taxi Driver, and the middle aged De Niro thoroughly entertaining in well-acted and sneaky-smart little comedies like Midnight Run and The King of Comedy, it’s been years since he’s done anything to merit the volumes of lofty praise that somehow still get attached to his name.

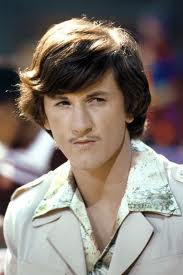

Meanwhile, right under our noses, a guy like Sean Penn has spent over three decades delivering one jaw-dropping performance after another, and in the process made a compelling case for himself as the single greatest screen actor the world has known since a young Marlon Brando.

And yet, somehow, most of us have not even bothered to notice it.

And yet, somehow, most of us have not even bothered to notice it.

Think about the youthful Penn stealing scene after scene in such terrific but long-forgotten movies as Racing with the Moon, Falcon and the Snowman, and in particular, At Close Range. Hell, even the iconic, 80’s Gen-X comedy, Fast Times at Ridgemont High.

Think about how a few years later a more grown up version of Penn would be able to instill a certain brand of flawed humanity into such terrific and often overlooked films as, to name just a few, Carlito’s Way, Dead Man Walking, The Crossing Guard, The Pledge, Sweet and Lowdown, 21 Grams, The Thin Red Line, The Assassination of Richard Nixon, The Interpreter, Fair Game and Milk.

Think about that. And I mean it when I say that is truly just a partial list.

Think about that. And I mean it when I say that is truly just a partial list.

It almost blows the mind how amazingly real and how impossible not-to-watch Sean Penn has been over the course of his career. And yet, somehow, he’s never found himself being mentioned in the same breath as the all-time greats like Bogie, Brando, Newman, Dean and Tracy.

Yet, for my money, that’s exactly the company in which he belongs.

Yet, for my money, that’s exactly the company in which he belongs.

This is going to sound a little esoteric, but I think of Penn as the Fredric March of his day; a guy who's been so damn good for so damn long that the only thing more remarkable than how good he’s been, and how long he’s been so, is how damn long we’ve taken it for granted.

I bring this up today because I was cleaning out my desk and I pulled out an old clipping from October 3, 2003. It was the New York Times Weekend section from that date which contained A.O. Scott’s glowing review of Clint Eastwood’s film version of the Dennis Lehane novel, Mystic River. What the Times’ critic had to say about Penn so moved me, and was so spot-on and so effusive, I was compelled to keep it.

And today I feel compelled to share it with you, knowing full well that not much more needs to be said about Sean Penn, the actor, beyond what Mr. Scott wrote so beautifully and succinctly nine years ago:

And today I feel compelled to share it with you, knowing full well that not much more needs to be said about Sean Penn, the actor, beyond what Mr. Scott wrote so beautifully and succinctly nine years ago:

Mr. Eastwood has found actors who can bear the weight and illuminate the abyss their characters inhabit. Mr. Penn, his eyes darting as if in anticipation of another blow, his shoulders tensed to return it, is almost beyond praise. Jimmy Markum is not only one of the best performances of the year, but also one of the definitive pieces of screen acting in the last half century, the culmination of a realist tradition that began in the old Actor’s Studio and begat Brando, Dean, Pacino and De Niro.

But Mr. Penn, as gifted and disciplined as any of his precursors, makes them all look like, well, actors. He has purged his work of any trace of theatricality or showmanship while retaining all the directness and force that their applications of the Method brought into American movies.

The clearest proof of his achievement may be that, as overpowering as his performance is, it never overshadows the rest of the cast. This tragedy, after all, is not individual but communal, even though each character must bear it alone.