A few thoughts about former Yankee second baseman Gil McDougald, who passed away this week after a bout with prostate cancer:

A few thoughts about former Yankee second baseman Gil McDougald, who passed away this week after a bout with prostate cancer:

As wonderful a player as he turned out to be, he never should have won Rookie of the Year over Chicago's Minnie Minoso in 1951. Taken in light of the cavernous ballpark Minoso called home that year and the anemic hitters surrounding him, the White Sox #3 hitter was an absolute wonder.

Consider the respective stat lines of the two rookie stars:

Minoso: .326 BA, .422 OBP, 24 2B, 14 3B, 10 HR, 76 RBI, 112 R, 31 SB

McDougald: .306 BA, .396 OBP, 23 2B, 4 3B, 14 HR, 63 RBI, 72 R, 14 SB

They say it's never the crime; it's the cover up.

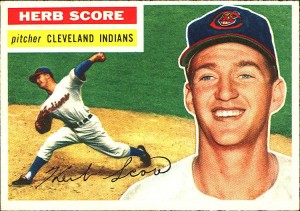

And with McDougald, it wasn't so much that he hit potential Hall of Famer Herb Score in the face with a line drive in 1956, effectively ending his career. It was how he handled himself in the aftermath that ultimately defined him.

McDougald told writers the very evening he hit Score that if the Cleveland All Star were to be blinded as a result, the Yankee second baseman would retire on the spot. At the time he was 27 years old.

McDougald told writers the very evening he hit Score that if the Cleveland All Star were to be blinded as a result, the Yankee second baseman would retire on the spot. At the time he was 27 years old.

He reportedly often got sick to his stomach long after Score's beaning at the mere image of Indians' pitcher lying motionless on the mound, and for years regularly reached out to Score via phone calls and letters.

* * * * * * * * * *

Ironically, just nine months before hitting a ball that almost killed Score, McDougald himself was the victim of a line drive to the head. During batting practice in August of 1955, teammate Bob Cerv ripped a liner that caught McDougald flush in the ear, knocking him to the ground.

Though he shook off the blow and only missed two games, he began to suffer significant hearing loss and by the 1980's had gone completely deaf. The deafness, which he shared with no one, caused McDougald to retreat from baseball entirely and to withdraw into a small circle of family and close friends.

Though he shook off the blow and only missed two games, he began to suffer significant hearing loss and by the 1980's had gone completely deaf. The deafness, which he shared with no one, caused McDougald to retreat from baseball entirely and to withdraw into a small circle of family and close friends.

It wasn't until he admitted in a 1994 interview with Ira Berkow of the New York Times he was totally deaf that any of his old baseball friends actually learned of McDougald's condition.

And as a result of that interview, however, the former All Star learned about cochlear implants from some Times readers, which then led him to get an operation which restored his hearing after more than a decade of total deafness.

* * * * * * * * * *

A few other items I discovered in researching Gil McDougald's storied career: