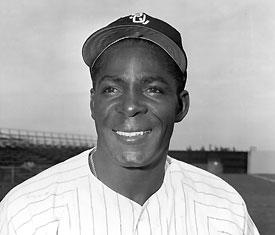

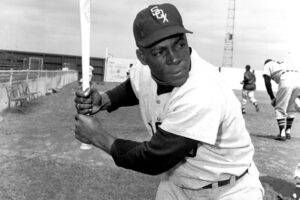

We were driving back to Comiskey Park. It was 1980; April to be exact. I was roughly a year into the first real job of my life, as a low-level ticket-hawker, gofer and all-purpose grunt for the Bill Veeck-era Chicago White Sox. And on that day Minnie Minoso and I were seated in the front seat of the company wagon tooling along – me behind the wheel, him riding shotgun – and breaking our rather pregnant stretches of silence with snippets of small talk about the weather, the start of the baseball season, and the off-chance that the perennially underfunded and outmanned Sox might actually rise up and surprise a few people.

We were driving back to Comiskey Park. It was 1980; April to be exact. I was roughly a year into the first real job of my life, as a low-level ticket-hawker, gofer and all-purpose grunt for the Bill Veeck-era Chicago White Sox. And on that day Minnie Minoso and I were seated in the front seat of the company wagon tooling along – me behind the wheel, him riding shotgun – and breaking our rather pregnant stretches of silence with snippets of small talk about the weather, the start of the baseball season, and the off-chance that the perennially underfunded and outmanned Sox might actually rise up and surprise a few people.

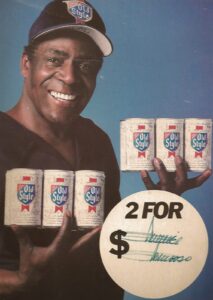

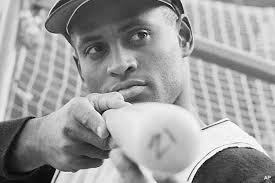

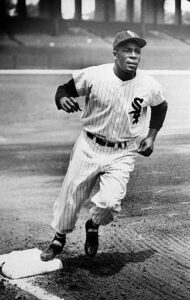

That particular morning, a warmish Saturday, Minnie had just done one of the hundreds of public appearances he would make over the course of his decades as an ambassador for the team. He’d shown up, dapper as ever, signed autographs, kissed cheeks, shook hands, and told any number of dog-eared stories at a small Mexican festival in a run-down, likewise dog-eared community just south of the city, where he had been hailed – as he always would be in Latin neighborhoods around town – as a folk hero.

But on the way home, when we pulled off the road to gas up, something happened that stuck in my mind, and only in the last few days did I realize its true significance.

But on the way home, when we pulled off the road to gas up, something happened that stuck in my mind, and only in the last few days did I realize its true significance.

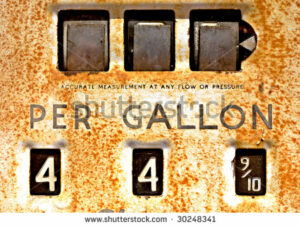

Let me explain. It was 1980, keep in mind. The U.S. was being held hostage in Iran and gas prices were skyrocketing from coast to coast. In fact, for the first time ever the price of gas had shot up to $1.00 a gallon. It was unheard of. And, given that prices soared so dramatically so quickly, coupled with the fact that pump manufacturers likely never dreamed of a per-gallon price anywhere near three digits, gas pumps in and around Chicago could only be set as high as .99 cents a gallon.

No station owner knew what do to, because none had ever seen anything like it. So that day, before the attendant began pumping, he leaned in and explained that, to adjust for the pump’s inability to handle the $1.00 per gallon price, he’d been forced to set the per-gallon price at .50 – so whatever the display read, I'd owe him twice that. I said fine. Give me $30.

No station owner knew what do to, because none had ever seen anything like it. So that day, before the attendant began pumping, he leaned in and explained that, to adjust for the pump’s inability to handle the $1.00 per gallon price, he’d been forced to set the per-gallon price at .50 – so whatever the display read, I'd owe him twice that. I said fine. Give me $30.

As he was sitting there, his mind adrift, Minnie either didn’t grasp the concept or didn’t hear the conversation. As a result, when the guy was done and replaced the nozzle, the pump read $15 – which Minnie saw, as it was next to him at eye level. But when the attendant casually said that would be $30, my partner’s ears pricked up, he did a double take toward the pump and then spun his head violently in the direction of my open window.

As he was sitting there, his mind adrift, Minnie either didn’t grasp the concept or didn’t hear the conversation. As a result, when the guy was done and replaced the nozzle, the pump read $15 – which Minnie saw, as it was next to him at eye level. But when the attendant casually said that would be $30, my partner’s ears pricked up, he did a double take toward the pump and then spun his head violently in the direction of my open window.

He then leaned far over toward the driver’s side, almost at face-level with me and began pointing at the attendant, his nostrils flaring and his eyes burning. “You can’t do that!” he barked in his broken English. “It say $15,” he spit out, pointing behind him with one hand, “Not $30!!!” I tried to calm him down and explain, almost laughing, that everything was under control. But he wanted no part of it. He was mad as hell – madder, in fact, than I would ever again see him. Regardless of what I said that morning, Minnie Minoso was flat-out not going to be taken advantage of; certainly not by some guy in a jump suit pumping gas.

For years, I'd thought about that incident. And for years I fooled myself into thinking Minnie just simply didn’t grasp the math. In fact, I would often tell stories about my Sox days, and that one always triggered some gentle chuckles. Hell, I spent the better part of my life believing his rage that day was because of some conceptual gap he had, or maybe an inability to wrap his brain around a basic principle of grade school arithmetic.

For years, I'd thought about that incident. And for years I fooled myself into thinking Minnie just simply didn’t grasp the math. In fact, I would often tell stories about my Sox days, and that one always triggered some gentle chuckles. Hell, I spent the better part of my life believing his rage that day was because of some conceptual gap he had, or maybe an inability to wrap his brain around a basic principle of grade school arithmetic.

But all that changed the morning I heard Minnie died. I was listening to WBEZ, my local NPR affiliate, over coffee. A seasoned, whip-smart reporter named Yolanda Perdomo was reflecting on an extensive, straight-from-the-heart interview she’d once done with Minoso. Perdomo said she’d told Minnie before she  rolled tape that she didn’t want to do just another baseball Q&A, and that she wanted him to take her back to his early days in this country, to talk about what sort of issues he encountered, both as a black man and as a non-English speaking Cuban, and to tell her exactly what he felt the moment he’d heard that Jackie Robinson had broken baseball’s color barrier.

rolled tape that she didn’t want to do just another baseball Q&A, and that she wanted him to take her back to his early days in this country, to talk about what sort of issues he encountered, both as a black man and as a non-English speaking Cuban, and to tell her exactly what he felt the moment he’d heard that Jackie Robinson had broken baseball’s color barrier.

That interview, she told the WBEZ anchor, ended up taking two hours.

And as I listened, more intently than ever, Perdomo explained that since Minnie, despite living in this country for over seven decades, still spoke poor English, he made a deal with her. He'd agree to an interview on one condition; that she conduct it in Spanish. So she did. And the reporter told how Minnie went into great detail and spoke emotionally about getting the news about Robinson, and how much it had meant to him and black players everywhere to suddenly have a shot of one day playing in the big leagues.

As she spoke I thought about what it must have been like to be young black Cuban immigrant who spoke little English in 1947. I thought of how lonely that must have felt and how many times someone in those shoes faced people who tried to take advantage of his lack of English or understanding of our ways.

As she spoke I thought about what it must have been like to be young black Cuban immigrant who spoke little English in 1947. I thought of how lonely that must have felt and how many times someone in those shoes faced people who tried to take advantage of his lack of English or understanding of our ways.

And it was then that the realization hit me like a bolt. It was then I began to finally understand that what happened that day so many seasons ago was not about Minnie Minoso’s lack of understanding. It was about mine. It was about something that I, as a twenty-something year-old middle class white kid from a squeaky clean and well-maintained patch of post-war America, could never begin to comprehend.

And as I realized it, tears began to well up in me as I thought of my long ago co-worker. And as that happened I started to feel a chill creep down my spine. I realized Minnie wasn’t upset with the man at the gas station because his mind couldn’t wrap itself around the math. He was upset because for, for one sliver of an instant,  something about that guy trying to charge double for something the sign said cost half as much catapulted him back in time; back to a point in his youth – a point in this country’s history – that he’d spent every waking moment since trying to forget and, in a very real way, rise above; an era during which in many parts of this country it was open season on men of color, when a black man – particularly a young black man who barely spoke the language – served as fair game for every hate-filled bigot, redneck and small-minded turd within a stone’s throw. That moment, I suddenly realized, was a memory trigger for Minnie – only not a good one.

something about that guy trying to charge double for something the sign said cost half as much catapulted him back in time; back to a point in his youth – a point in this country’s history – that he’d spent every waking moment since trying to forget and, in a very real way, rise above; an era during which in many parts of this country it was open season on men of color, when a black man – particularly a young black man who barely spoke the language – served as fair game for every hate-filled bigot, redneck and small-minded turd within a stone’s throw. That moment, I suddenly realized, was a memory trigger for Minnie – only not a good one.

I put one hand on my forehead and thought to myself, “Dear God, how could I have been so stupid?”

There is, of course, a bittersweet symmetry to the recent deaths of Ernie Banks and Minnie Minoso, which, sadly, occurred days apart in a winter brutal even by Chicago's lofty standards; one a yin to the other’s yang. Banks was Mr. Cub; Minnie the franchise icon for the Sox. Banks represented the North Side; Minnie the working class neighborhoods south of Madison. Banks remained a National Leaguer to the core; Minnie a dyed-in-the-wool A.L man.

There is, of course, a bittersweet symmetry to the recent deaths of Ernie Banks and Minnie Minoso, which, sadly, occurred days apart in a winter brutal even by Chicago's lofty standards; one a yin to the other’s yang. Banks was Mr. Cub; Minnie the franchise icon for the Sox. Banks represented the North Side; Minnie the working class neighborhoods south of Madison. Banks remained a National Leaguer to the core; Minnie a dyed-in-the-wool A.L man.

But these two legends shared many things in common too. And two of those things, in particular, should never be forgotten. Because, even though most of us never even acknowledged their existence, those two things remain lasting gifts for which all baseball fans – or maybe even all people – owe both Minoso and Banks a deep, profound and eternal debt of thanks.

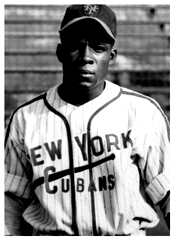

First was that each man spent his life both a victim and a product of an era in which hatred and bias in this country were not only largely accepted, in many states they were legally sanctioned. And both spent their formative years with one foot in the Negro Leagues and one on the dark and lonely trail of integration. And, inasmuch, both likely faced more hatred, bigotry, or ignorance than anyone should ever be subjected to, much less two men of such decency, gentleness and depth of character.

First was that each man spent his life both a victim and a product of an era in which hatred and bias in this country were not only largely accepted, in many states they were legally sanctioned. And both spent their formative years with one foot in the Negro Leagues and one on the dark and lonely trail of integration. And, inasmuch, both likely faced more hatred, bigotry, or ignorance than anyone should ever be subjected to, much less two men of such decency, gentleness and depth of character.

And as baseball fans, we owe them more than a tip of the cap for the fact that, somehow, even as they moved among us, smiled for us and shook our hands, each man’s almost childlike joy and boundless optimism had a way of making us completely forget all the hatred and venom that certainly must have once been so much a part of their lives.

But the thing for which we truly owe them is what they taught us -- showed us really -- about the best way, in fact that only way, to overcome boundless hatred.

With boundless love.

You see, both Minoso and Banks fought hatred the only way they knew; by battling it with the goodness within them. Because to have watched each closely, and in the case of Minnie, to have actually gotten to know him, I truly believe that’s how he felt, and that’s how he chose to deal with what, as a young man, must have seemed like a lifetime’s worth of racial epithets, physical threats, and long, lonely stretches of fear and doubt.

You see, both Minoso and Banks fought hatred the only way they knew; by battling it with the goodness within them. Because to have watched each closely, and in the case of Minnie, to have actually gotten to know him, I truly believe that’s how he felt, and that’s how he chose to deal with what, as a young man, must have seemed like a lifetime’s worth of racial epithets, physical threats, and long, lonely stretches of fear and doubt.

And to have braved such things and still have become known less for his stunning baseball skills – which, let’s be honest, remain among the finest ever – than his warmth, humanity and astounding optimism, almost defies logic. But it stands to reason when you think about it, because more than Minnie Minoso (and Ernie Banks) ever taught us about baseball, he taught us about the healing power of love.

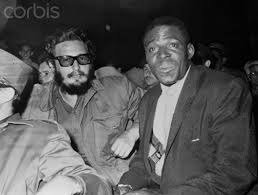

Minnie never did learn my name. Like so many of the interchangeable young, well-scrubbed faces he’d worked with over the years, I was simply that; just another young, well-scrubbed face. But inasmuch, I was eventually honored with a nickname by the guy; two of them actually. For a long time I was “Blue Eyes.” But when for a brief spell I grew a full beard, I became “Fidel.” And to me, he was always "Señor."

Minnie never did learn my name. Like so many of the interchangeable young, well-scrubbed faces he’d worked with over the years, I was simply that; just another young, well-scrubbed face. But inasmuch, I was eventually honored with a nickname by the guy; two of them actually. For a long time I was “Blue Eyes.” But when for a brief spell I grew a full beard, I became “Fidel.” And to me, he was always "Señor."

Nevertheless, despite his never really getting to know me, or even my name, I fell in love with Minnie Minoso. Like so many who crossed his path, I was captivated by his eternal love and found myself drawn to his unbridled passion for not just baseball and his Sox, but his adopted country, a place that had given him so much.

In fact, on the morning he died, Perdomo said that at one point in her interview Minnie told her he loved this country so deeply that when he is among fans he feels like he did back in Cuba in his mother’s arms.

Think about that for a moment.

Think about that for a moment.

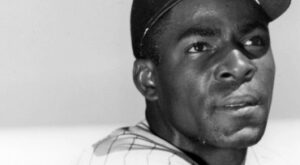

As hard as it is to believe, at least if you love the Sox, Minnie is gone now. A few days ago I walked over to his memorial service to say goodbye and offer a prayer. Somehow, despite what the years had done to kick the crap out of me, when I looked down saw him lying there, my old work buddy didn’t look so different from when I used to chauffeur him around. Looked, in fact, like he could still take two and hit one hard the other way.

And as I stood there quietly, mouthed my silent prayer, and said adios one final time, I looked at Minnie, laid out all dapper and peaceful, and thought three things.

I thought of that day at the gas station nearly a lifetime ago, and how just for a moment he pulled back the curtain and revealed a tiny trace of the hurt he managed to hide so well for so long

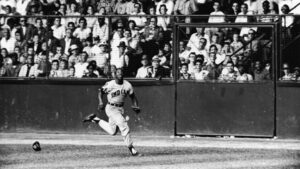

I thought about his jaw-dropping skills as a hitter, fielder and baserunner, how he’d come up just short in his bid for enshrinement in Cooperstown, and how so many of his opponents still contend he was one of the three or four greatest players of the 1950s; arguably, the richest, deepest and most storied decade in baseball history.

I thought about his jaw-dropping skills as a hitter, fielder and baserunner, how he’d come up just short in his bid for enshrinement in Cooperstown, and how so many of his opponents still contend he was one of the three or four greatest players of the 1950s; arguably, the richest, deepest and most storied decade in baseball history.

But mostly I thought what Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda once said about him not all that long ago. “Orestes Minoso was the Jackie Robinson for us; the first star who opened doors for Latin American ballplayers. He was everybody’s hero. I wanted to be Minoso. Clemente wanted to be Minoso.”

Again, think about that for a moment.

Yes, in a Hall of Fame sense, Minnie remains on the outside looking in, and I suppose that will be to our everlasting shame. But in another, that hardly seems to matter. Because the man will always be remembered as something far more profound than a mere Hall of Famer.

Minnie Minoso is, was and will always remain the Jackie Robinson of his kind, the most baseball-loving, baseball-crazy people in the history of the planet; the guy who as a young man, all alone and without the ability to even speak the language, bravely set out to carve a path others like him might one day follow; and the guy who a young Puerto Rican future baseball god with the musical name of Clemente once used to go to bed at night wanting to grow up to be.

Minnie Minoso is, was and will always remain the Jackie Robinson of his kind, the most baseball-loving, baseball-crazy people in the history of the planet; the guy who as a young man, all alone and without the ability to even speak the language, bravely set out to carve a path others like him might one day follow; and the guy who a young Puerto Rican future baseball god with the musical name of Clemente once used to go to bed at night wanting to grow up to be.

Because, let’s be honest, being a baseball hero is one thing. But being the hero of a hero’s hero?

Because, let’s be honest, being a baseball hero is one thing. But being the hero of a hero’s hero?

Being a role model to the most iconic, beloved Latin ballplayer the game has ever known – not to mention, just maybe, its finest gentlemen and most mythical figure?

That, as they say, ain't hay.

And – as I’m sure countless Latin ballplayers, fans, dreamers and sandlot urchins on fields up and down Central and South America would agree – I’ll take being remembered as Roberto Clemente’s hero over a bust in the Hall of Fame any day.

Vaya con Dios, Señor. Y gracias por todo lo que me enseñaste, mi amigo.

Para siempre,

Blue Eyes

(Fidel)

I wouldn't mind paying a buck a gallon today. I did not know much of anything about Minnie Minoso, although I was familiar with the name. I was more of an NYC sports person. Thanks for giving him his props. Also I have a shout out to the recently departed Gene, Gene, the dancing machine. Thanks for the laughs.

T: Gene Gene was so period-specific, so finite, I'm not sure anyone who didn't live through that era could ever wrap their brains around just how unlikely yet indelible his 15 minutes were. Adieu Gene. And you're right; thanks for the laughs.

[…] M.C. Antil reflected on the late Minnie Minoso. […]

[…] M.C. Antil reflected on the late …read more […]

In the last few weeks I have read a lot about Miñoso, but this is, by far, the best. Most of all, I found your article very sincere and, I have to say it, very moving. You see, I'm from Cuba too and Miñoso has been my hero since I was a kid and I was lucky enough to see him playing with a Marianao's baseball uniform in the last season he played in Cuba. When he passed away, I felt as I lost a close relative. Thanks!

Thank you so much, Lector. That is a wonderful thing to say and and even more wonderful thing to hear. I hope you'll take a moment to share my brief reflection of Minnie with others who may enjoy it. And, again, thanks. My condolences on someone we all lost, but who gave us all some great memories and even greater joy.

[…] M.C. Antil reflected on the late Minnie Minoso. […]

What a fine, honest and insightful article. As a child and teenager in the 50's and 60's, I was well aware of many of Minnie Minoso's accomplishments. Although I agree that he should be remembered as a dyed-in-the-wool A.L. man, he did spend a not so memorable year in the N.L. with the St. Louis Cardinals. In fact, my father and I were in attendance (and sitting far down the left field line) the day he smashed into the left field wall. Although it was rather late in his career (I believe it was May, 1962) he was still showing his all-out hustle as he attempted to make a great catch. He hit the wall so hard, he had to be carted off the field on a stretcher. It made a sickining sound as he fell to the ground. I'm 65 years old now, but I'll never forget that day. Unfortunately, because of that injury, he played less than 40 games for the Redbirds. After '62, he returned to the American League for his final two seasons.

Thanks so much, Ace. Baseball is nothing if not a vehicle for great lifetime father-and-son memories. I appreciate your sharing one of yours. And good luck to your Redbirds this year.