Eleven years ago, as I was battling throat cancer, I took on a project that would end up one of the most rewarding of my life. As I lay there trying to ward off the effects of twenty or so bouts of high-dosage radiation, I decided to put together a list of my 300 favorite pop singles from the 1960’s – the ten-year stretch of time that had helped shape who I am – and then write a brief essay about each 45 and why the record still mattered to me after all these years.

Eleven years ago, as I was battling throat cancer, I took on a project that would end up one of the most rewarding of my life. As I lay there trying to ward off the effects of twenty or so bouts of high-dosage radiation, I decided to put together a list of my 300 favorite pop singles from the 1960’s – the ten-year stretch of time that had helped shape who I am – and then write a brief essay about each 45 and why the record still mattered to me after all these years.

I called this year-long retrospective my very own "Desert Island Jukebox."

Enter my younger sister, Dee.

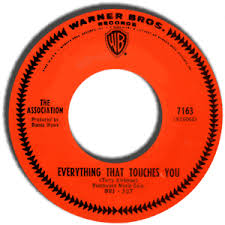

Song #158 on my imaginary juke box was an original penned and sung by the Association, a bouncy, achingly beautiful little ballad called Everything that Touches You. Dee, who was going through a hard time for reasons that, frankly, escape me, read what I’d written and clicked on the video I’d embedded. She’d never really heard Everything... before, but something about it filled her with a sense of hope – while easing, if only by degree, the pain she’d been hauling around.

Because she’d been so supportive as I was writing this book I’d been working on, I felt I wanted to do something nice. So, I figured I’d write an essay about the song, while providing a handful of sausage-making anecdotes about it.

It was a Saturday afternoon, I remember, and I'd found his number using this handy-dandy app I discovered. Terry Kirkman, Association co-founder, vocalist, and composer of Everything That Touches You, answered after three rings.

We barely had time to say hello, much less exchange pleasantries. Instead, he gently barked in a distracted voice, “I’m sorry. We’re in the middle of a plumbing problem. Can I call you back?”

That was it, or so I thought. I mean, the guy never even asked for my name or number.

So much, I figured, for writing an essay on what I still contend is one of the most underrated love songs of the latter half of the 20th century.

Yet, three hours later, sure enough, my phone rang. “Is this Michael?” the voice asked. I immediately tried to explain that ever since I was a kid – considering I’d been born Michael Charles III – people had always just used my initials, "M.C." But that little kernel of info didn’t seem to take. To the guy on the other end, my name was Michael, and it would remain Michael for as long as he lived.

“This is Terry Kirkman,” he said. “Sorry about before. What can I do for you?”

Considering this essay is now less a nod to my sister than it is a tribute to one of the most underappreciated pop artists of my Wonder years, the first thing I hope you’ll bear in mind is that Terry actually called me back – and did so hours later, his plumbing problems, apparently, deep in his rear view mirror.

I thanked him and told him about my reason for reaching out, at the same time asking if he wouldn’t mind sharing a story or two about Everything that Touches You. I explained about my sister and how much the song had meant to her at a time she needed something to hold onto. Told Terry, too, how, as a way of easing her pain, she’d regularly play it in bed before nodding off to sleep.

That’s when, in a moment that I realized later defined him, Terry asked, “How’s she doing now?” before adding, “Tell your sister I’m glad my song helped her, OK?”

That’s when, in a moment that I realized later defined him, Terry asked, “How’s she doing now?” before adding, “Tell your sister I’m glad my song helped her, OK?”

That first conversation lasted almost two hours, and we talked about everything under the sun – except, it seemed, music. Every time I’d ask him about the Association, a song he’d written, or maybe an album his band had recorded, he’d demur and change the subject.

Terry, you see, had left the music industry decades prior. Following declining interest in the band he’d help form, and following a period of personal dependence on drugs and alcohol, he retreated from music almost entirely.

By the time we first talked, he’d gotten sober, he’d gotten divorced, he’d remarried, and he’d become fully dedicated to his new life as a counselor for fellow substance abusers. And, by most all accounts, he’d become really, really good at the last of those things.

But, still, he’d rarely talk about music and would simply hem and haw whenever the subject came up.

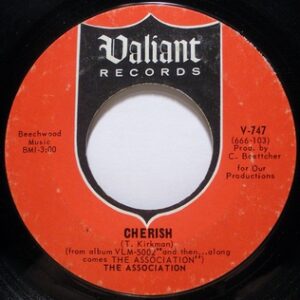

Finally, during that first conversation, and out of a desperation that just seemed to well up inside me, I said something that came out as unvarnished as a 2x4. “Terry,” I said, “no offense, but f*uck you. Seriously, f*ck you. Look, I know you’ve done a lot of good for a lot of people in your new life. But you’re an idiot if you try to pretend your old one never happened. You sang on three of the most requested recordings of the 20th century, one of which you wrote. Do you know how many people our age fell in love to Cherish, danced their first dance to Cherish, maybe even sang Cherish to the other one on his or her deathbed? I mean, do you have any idea how many artists would kill to have had that kind of impact? Like I said, Terry, f*ck you and that bullshit, woe-is-me act of yours.”

After a pregnant pause – a speech pattern I’d soon learn was one he embraced with full rigor – he said into the receiver without even a trace of unease, “I like talking to you.”

And that, I suppose, was the beginning of our friendship.

The next few times we spoke, it was me initiating the conversation by calling Terry. But, in time, he’d call me just as often as I called him. And, indeed, we eventually began talking about music.

Terry Kirkman, you see, was at his core an artist. A true lover, maker and consumer of art in whatever shape or form he found it. And, no matter where he went, and no matter what he did, an artist’s heart could always be found beating inside him. And while music might have been the art form that would prove to be his first love, it wouldn’t by any means be his last.

In fact, one of my favorite conversations with him was not long after he and his wife Heidi had visited, I think, the Norton-Simon Museum in Pasadena, a place he loved. When we spoke a short time later, I remember thinking I’d never heard him so animated. Terry couldn’t stop talking about a piece he’d seen by Ellsworth Kelly, a noted American minimalist who in the mid-20th century often used simple shapes and bright primary colors to explore such complex and, at times, hard-to-define human concepts as truth, beauty and isolation.

The piece, titled Green Angle, was a large three-dimensional obtuse angle, painted green and suspended downward from the wall. It completely captivated Terry, who told me he spent almost an hour just staring at it and trying to figure out what it was Kelly was trying to say with it.

The piece, titled Green Angle, was a large three-dimensional obtuse angle, painted green and suspended downward from the wall. It completely captivated Terry, who told me he spent almost an hour just staring at it and trying to figure out what it was Kelly was trying to say with it.

Then, he told me, he looked at Green Angle not head-on, but from one side. It was there, he said, that he discovered the artist had left a small portion of his work unpainted. Kelly had left, in other words, a section of bare wood as part of his larger statement. That’s when Terry’s retelling of the moment found a higher gear. That’s when the pitch in his voice rose and his vocal energy ratcheted up to a level that, to be honest, I’d never quite heard from him before. He began going on and on about man’s basic nature.

I frankly don’t remember all Terry said about Green Angle, because I was too busy feeling a sudden pang of sorrow for this gentle man who’s dream of making art – in his case, writing songs and making records – had been so stripped from him while he was still just a kid, and done so by an industry that remains to this day notoriously soulless – so much that Joni Mitchell once referred to it as “the star-maker machinery behind the popular song.”

I could go on about Terry’s passion for art, but instead let me share with you a few of the more salient points he shared about his brief music career:

with a phrase, such as, “I love you,” “Go to Hell,” “Come back to me,” and “What were we thinking?” When his first label, a tiny entity called Valiant Records, was gobbled up by giant Warner Bros., Warner wanted a new album right away and gave Terry and his mates something like three months to get it to them. One night in a panic, Terry went home, took all his manila envelopes, and dumped them out on the dining room table he and his first wife had just bought. He then began mixing and matching all the various ideas he’d amassed. At one point, a young songwriter he was mentoring came up behind him, looked over one shoulder while eating a ham sandwich, and said as he pointed, “No. Put that one over there.” Terry did . And before you could say "Tin Pan Alley," Everything that Touches You had gone from a few scribbled ideas to a fully realized composition, and one that would stand the test of time like few others he’d ever write.

with a phrase, such as, “I love you,” “Go to Hell,” “Come back to me,” and “What were we thinking?” When his first label, a tiny entity called Valiant Records, was gobbled up by giant Warner Bros., Warner wanted a new album right away and gave Terry and his mates something like three months to get it to them. One night in a panic, Terry went home, took all his manila envelopes, and dumped them out on the dining room table he and his first wife had just bought. He then began mixing and matching all the various ideas he’d amassed. At one point, a young songwriter he was mentoring came up behind him, looked over one shoulder while eating a ham sandwich, and said as he pointed, “No. Put that one over there.” Terry did . And before you could say "Tin Pan Alley," Everything that Touches You had gone from a few scribbled ideas to a fully realized composition, and one that would stand the test of time like few others he’d ever write.

Gene Puerling (l) and Clark Burroughs (c) of the Hi-Lo's

It was also at Warner, he told me, that he and his bandmates were first introduced to Clark Burroughs, who was more than half a generation older than they were. Burroughs, a former child actor, had served as lead vocalist and tenor of a 1950’s quartet called the Hi-Lo’s, the brainchild of a Milwaukee boy named Gene Puerling, who'd formed them just as the big band era was riding off into the sunset. Puerling’s idea was to take many of the arrangements of the best of those bands – in his case, I believe, Stan Kenton’s – and apply all the parts Kenton had written for brass instruments to the human voice. The Hi-Lo’s vocal impact was so deep, so profound, and so incredibly lasting that if you lined up all the artists who’ve stood on their shoulders you’d realize that many of the biggest American singing groups of the 60’s – Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys, the Mamas and Papas, Jan and Dean, the Fifth Dimension, Spanky and Our Gang, the Grass Roots, the Lovin’ Spoonful, Three Dog Night, and yes, the Association, to name but a few – all shared the same roots, and all traded on a harmonic style that traced directly back to the big band arrangements of men like Benny Goodman, Billy Strayhorn, and, of course, Kenton. The “new” California sound of the 60’s, in other words, was actually just a reimagining of the legendary big band sound of the 40’s – only one not played this time around, but sung.

Terry (l) and the Association on the opening night of the Monterey Pop Festival

The Mama’s and Papa’s producer and manger, Lou Adler, had once asked Terry and the Association to be the opening act for a huge outdoor festival he and John Phillips were planning up in Northern California. He said they were going to call it the “Monterey International Pop Festival.” Terry had just written a somber yet wildly evocative anti-war anthem that described a young bullfighter dying alone in the dust, and doing so for reasons he could never fully understand. The song was a perfect metaphor for the growing quagmire in Vietnam and the deaths of so many American boys in so many distant jungles. He called it – a song he not only wrote, but on which he sang lead and played the French horn – Requiem for the Masses. Terry implored his mates to open their Monterey set with it, but they balked. Their bass player, Brian Cole, who’d soon die of a heroin overdose, had just written an Association “music machine” bit that was as much schtick as it was an exercise in creativity, but was something that, in future performances, they'd all eventually use as a segue to Cole's countdown of their Top Ten hit, Along Comes Mary. The decision not to play Requiem broke Terry’s heart, though I’m not sure he ever really told the rest of the band that – at least not then. Even though the Association would eventually nail their bass player's Devo-like opening, and perform Along Comes Mary spotlessly, both fell mostly flat – especially given the crowd's makeup and the fact that at the time kids everywhere, but especially in California, were chin-deep in such things as self-discovery, mind-expansion, and, yes, Vietnam. The Monterey Pop festival would feature such legendary acts as the Who, Eric Burdon and the Animals, Janis Joplin, the Byrds, Canned Heat, the Jefferson Airplane, the Buffalo Springfield, Simon & Garfunkel and the Grateful Dead. What’s more, it'd be remembered, for then and evermore, as the coming-out party for two of the greatest Black artists of the century, both of whom blew folks away with their incendiary mix of talent, showmanship, and ferocity: Jimi Hendrix and Otis Redding. A few weeks later, Adler called. He told Terry he had bad news. The Association would not be included in the concert film the promoters had shot and were in the process of editing, one that would soon be released coast to coast. His band was great, Adler told Terry. But their set just didn’t fit with the mood of the festival, the one they were trying to capture with the movie. Just as I’d never heard Terry more animated as he was when he was talking about Green Angle, I’d never again hear him any more regretful than when discussing the ill-fated choice his bandmates had made that weekend. “I really believe,” he said, “that if we’d opened with Requiem, we might have been viewed differently by critics, and that our career might have gone in an entirely different direction. We had a chance to be something more than just another singles band, but…” His voice tailed off and he never entirely finished whatever it was he started telling me. He didn’t have to. I understood exactly.

There were so many other stories Terry shared with me in our conversations over the course of that year and a half – stories that ranged from the likes of John Hartford, Tommy Smothers, Glen Campbell, Mason Williams and the long-since-departed SoCal folk scene to legendary California artist Ed Ruscha, jazz icon Peggy Lee, and former Black Panther and Chicago 7 compatriot/martyr Fred Hampton – but in the interest of time, let me just cut to the chase.

Terry, like so many of us, had at least one issue that dwelt deep inside him, and one that would remain unreconciled for as long as he drew breath. That issue – having turned his back on his abilities as a pop tunesmith, if not his slavish love for crafting a pop record – would haunt him forever.

And please understand, I do not use the word “haunt” loosely – or, for that matter, "forever."

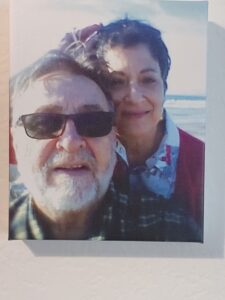

In fact, Heidi and I spoke a few times after Terry’s passing, and she communicated once how much having been chewed up and spit out by the music industry had eaten away at her husband’s sense of himself. In fact, while she accepts the fact that substance abuse had probably always been a part of Terry’s makeup, even as a kid, it wasn’t until his band was tossed aside by the very industry that had taken full advantage of it for as long as it behooved them to do so, his substance abuse problem only seemed to tighten its grip on his life.

I hardly knew Terry well. But I did know him some. And from what I could tell, he was affable and outgoing. Likewise, part of him seemed to relish maintaining the gruff and somewhat curmudgeonly veneer that he'd cultivated over the years. But if there was one thing I learned in our brief time, it was this: the Terry Kirkman I spoke with on all those phone calls took things to heart, and deep down inside he was a loving, sensitive, and caring man who could bruise as easily as anyone I ever knew.

A Terry and Heidi Kirkman selfie

The last time we talked, Terry told me two things that made me realize how much he’d come to view me as a friend. First, he confided that he’d just been diagnosed with congestive heart failure, a prognosis that needed no further explanation. “Jesus, Terry,” I said, knowing full well the implications of what he’d just shared, “I am so sorry.”

And secondly, he told me a few moments later about selling his catalog of songs to his agent, along with the understanding that the guy could then flip the publishing rights to Cherish and a number of his fringier hits to anyone who met his asking price. It was a sale for not nearly the amount of money he and his agent had originally been discussing. But, he told me, the clock was ticking. “I just want to be able to leave Heidi something,” he said. “I just want to be able take care of her.”

He could barely whisper that last part.

Following his death, Terry earned the kind of mentions that, on the surface anyway, were worthy of the depth and breadth of the fingerprints he’d manage to leave all over my generation. The New York Times, Los Angeles Times and Washington Post (not to mention major trade pubs like Variety and Billboard) all gave him nice, fully researched obits, complete with headlines and photos. His name and image were featured prominently during the Grammy Awards’ In Memoriam section. And, of course, he popped up in a number of those “Artists We Lost this Year” lists that one regularly stumbled upon as 2023 was ending.

As for me, I choose to remember Terry, even now, not for how he spent the final 50 years of his life, but how he lived the first 30. In that brief time, he composed and sang one song (Enter the Young) that would prove to be my own personal gateway drug for a kind of music that would forever speak to the absolute best part of me.

He wrote one of my favorite songs from my first full decade of musical awareness (Everything that Touches You), a tune that, fifty years later, my sister would subsequently use as the light at the end of her own personal tunnel of darkness and despair.

And he wrote one of the true touchstones of our shared generation (Cherish), a modern-day standard that would forever embody the kind of love that, at least for those of us of a certain age, would somehow remain just as pure and innocent as it was timeless.

But the song I choose to remember Terry by today – and the one I want to share with you now – is one he wrote for Goodbye Columbus, a largely obscure film from the Spring of 1969. The movie was based on Philip Roth’s first novel. It also featured Ali MacGraw in her first major screen role. The song wasn't great, by any means. But it was, in many ways, an almost perfect distillation of the twenty-something year old Terry Kirkman as a songwriter and performer, one that was both emotionally honest and unabashedly direct in its sentiment – not unlike, I suppose, its composer.

But the song I choose to remember Terry by today – and the one I want to share with you now – is one he wrote for Goodbye Columbus, a largely obscure film from the Spring of 1969. The movie was based on Philip Roth’s first novel. It also featured Ali MacGraw in her first major screen role. The song wasn't great, by any means. But it was, in many ways, an almost perfect distillation of the twenty-something year old Terry Kirkman as a songwriter and performer, one that was both emotionally honest and unabashedly direct in its sentiment – not unlike, I suppose, its composer.

Christened Brenda’s Theme by the producers (after MacGraw’s character), So Kind to Me was a romantic paean to a most vulnerable time in any young man’s life, when spike-horn, rutting bucks the world over – hopeful, earnest kids facing down the icy cold stare of manhood while trying their best not to appear even remotely unsure of themselves – often found comfort in the warmth and glow of a beautiful fellow-traveler.

And to hear Terry sing his own words, especially during So Kind to Me’s gentle, sweet fade-out, is moving in ways I still have trouble articulating. That's when the phrase "You were so kind to me" gets joyously repeated over and over. When that happens, it almost feels as though the singer is thanking the young woman before him, not so much for her love, or her beauty, or even her companionship. He's thanking her for, of all things, her kindness.

No moment in the history of vinyl screams "Terry Kirkman" any louder.

And to hear him and his mates chanting the constantly repeated refrain of the song's title is to hear Terry bravely opening his own heart and sharing the almost childlike mix of innocence and hope that he, somehow, always led with – an innocence that would prove to be both his greatest asset as an artist, and, alas, his biggest vulnerability as a professional.

Godspeed, Terry. And from the depths of my heart, thank you, not just for the gentle, loving songs you left us, but for the all-too-brief time we found ourselves fortunate enough to call each other friend.

Great piece M!

I even learned something new about you. Didn’t know your middle name was Charles.

Love your writing. Keep on keeping on.

Thanks, Charlie. It was never cool to have liked to Association, but there is certainly something to be said for music that has, somehow, managed to hold up all these years. Hope you're doing well, my friend.

Loved this MC. Like you, I grew up with the Association being part of the soundtrack of my life. I agree with your friend Terry, that had they opened Monterey with "Requiem", they would have been viewed differently. Sorry he never felt he received the recognition & respect he deserved as an artist. But he certainly sounds like he was an amazing human being. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks, Huck. He was a pretty remarkable guy. His parents sure did a heck of a job raising him, that's for sure. Be well, and thanks for reaching out.

MC….you got game

Richard Mulherin

Thanks so much, Dick. Terry, might have been born in Kansas and raised in California, but in every other way he was a Syracusan! Hope you're well, my friend.

Such a wonderful tribute to the man and the music that means so much to me. Well done, M.C.

Wonderful tribute! Loved the Association and this brought all those melodies back.

Thanks, Mike. It's shocking how many knowledgeable, discriminating music aficionados are coming out of the woodwork to echo your thoughts almost exactly. The Association, for all their supposed "poppiness," could really bring it as players.

Now, if we can only get JRod on track! 😉

Beautiful and moving tribute, M.C. Hope you are well.

Best wishes,

Bruce

Bruce!!! So great to hear from you! Crazy time in Israel, eh? I think of you often. I hope you're safe and doing well. We are currently abridging my book to fit into a single volume. Someone who's working with me believes in the story. She's just trying to make it more marketable to a national audience. Thanks for reaching out, and thanks so much for the kind words.

Wow. I was shocked to read when you told him

seriously F you but I’m sure your tone was spot on. Love the Windy recorder anecdote. If you’ll forgive a copyedit the word you want is demur not demure. Cheers pal

Excellent editing, Kent. Thanks, my friend. Hope you're doing well. BTW, Heidi later confided it might have been the F bomb incident that first opened Terry's eyes and heart toward me.

Well written, thoughtful, and moving.

Thanks, Bill. If anyone can appreciate how hard it must have been to turn your back on your gifts as an artist, it's you. If only Terry had had your sense of balance and commmitment. Thanks, again.

This captures Terry. I was fortunate enough to be a Facebook friend for a few years and enjoyed his postings and phone art. My favorite Association songs, are ETTY and Requiem. I’m a lyric lover and I think ETTY has lyrics that explain new live so perfectly. “In my most secure moments, I still can’t believe I’m spending those moments with you. The ground I am walking , the air that I breathe are shared at those moments with you.” Requiem is just brilliant. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks so much, Theresa. It's funny, speaking of lyrics, one time I told Terry that one of the most impressive things about ETTY was, in fact, its lyrics -- only not just the poignance or the poetry of them, but their cadence. And the next line after the one you cite, is the one that I happened to point out to him. "But I never suspected that one of those days, the wish in this song would come true" is an absolute perfect marriage of lyrics and meter. Each syllable sung becomes a note unto itself. Amazing. Thanks again. I really appreciate your thoughts and reflections.

MC – I just found your blog. This Kirkman piece blows me away on several levels. I’ve seen the “remnant” of The Association twice in the past few yeas on the Happy Together Tour. They still sound great after all these years. Not only is “Everything that Touches You” one of my all-time favorite songs, I’ve used the incredible bass line as a warm-up before 8:00 Mass. I have 404 songs on my 1960-1969 playlist, but it’s a playlist, not a retrospective. I’m looking forward to diving into all 10 parts! Finally – your writing style. It’s clean and readable, but at the same time paints such wonderful word pictures. That’s so hard to do. I’m looking forward not just to future pieces but diving into the archive!

Thanks, Peter. I'm still in touch with Terry's wife, Heidi, and she'll be delighted to hear your thoughts. Any other thoughts you have as you read, please don't be shy about sharing them with me. Cheers!