M.C. Antil’s Song of the Day — December 30, 2010

A snapshot of a song you might not know…but should

This may sound preposterous, but I am going on record right now as saying one of the most important songs in the history of music was an infectious but otherwise unassuming little ditty called "My Boy Lollipop," a song that in the spring of 1964 braved the crush of Beatlemania and somehow elbowed its way up to #2 on the pop charts.

And if you think that's just hyperbole, hear me out.

In the summer of 1959, a 23-year old beach bum named Chris Blackwell was kicking around his native Jamaica, teaching tourists how to water-ski and wondering what the hell he was going to do with his life. Blackwell, who came from a wealthy Jamaican family, loved music, especially jazz, and that summer borrowed a few thousand dollars to launch a Kingston-based record label, which he called Island Records.

Initially, Blackwell and his partner occupied themselves with finding and recording jazz artists on the island, and their very first release was a live album featuring a blind Jamaican pianist named Lance Hayward.

But even as they were focusing on jazz, there was a whole different brand of music emerging in Jamaica; one that was a unique blend of mento, calypso, British pop and American R&B. As he traveled around Kingston looking for emerging jazz talents, Blackwell sensed there was something new and far more exciting taking place in the streets and clubs of his homeland.

What he was hearing was an odd mix of island music many locals were calling ska -- a uniquely Jamaican hybrid that, following a few musical tweaks, a name change, a little luck, and Blackwell's particular brand of genius, would soon evolve into a full-blown global phenomenon.

But more on that in a moment.

After two years of kicking around, trying to turn Island Records into a respectable jazz label, Blackwell decided to start branching out and created a small subsidiary that specialized in Jamaican-flavored R&B. Islands' first three releases on its R&B subsidiary all went to #1 in Jamaica. But what intrigued Blackwell was the number of records he was able to sell in England, which by then had become home to growing number of Jamaican ex-pats.

So after two more years of licensing ska-flavored R&B records to a London-based jazz label, he decided to move Island Records lock, stock and barrel to England and have a go at tapping into the British market directly.

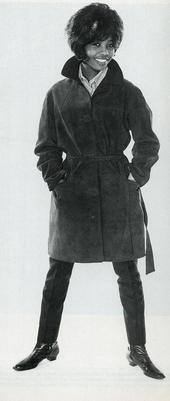

In July of 1963, convinced ska held huge crossover potential for the booming post-war generation of white teenage record-buyers, he flew a petite 15-year old Jamaican girl named Millie Small up from the Caribbean to record a couple of sides.

Small, a high-energy, cute-as-a-button little Black girl with a coquettish, baby doll voice, had recorded a number of hits in her homeland, which had in turn been licensed in the U.K. on Blue Note Records. As a result Small became known in the Jamaican sections of London and beyond as the "Blue Note Girl."

Blackwell knew that the infectious (and danceable) brand of ska that Small and many of her fellow Jamaicans produced would resonate with a young white audience if packaged properly, particularly in the U.K. Unfortunately, his first attempt at "packaging" ska for the white teenage market was a dismal failure.

For Small's first single, Blackwell had paired her with Harry Robinson and his "orchestra" of London-based sidemen, which recorded under the tongue-in-cheek moniker, Lord Rockingham's XI. Lord Rockingham had had a couple of novelty hits in the late Fifties, and as a result everything they did after that never drifted far from the full-bodied, over-the-top, sax-and-guitar sound that provided them their 15 minutes -- including "Don't You Know," Small's first attempt at a crossover ska hit.

"Don't You Know" wasn't a bad record, but in Robinson's zeal to create a house-rocking dance number, he completely buried the ska beat and the singer's infectious charm under a tidal wave of sax, organ and guitar. The overwrought single went nowhere. But more importantly, it failed to capture the essence of ska that Blackwell so desperately wanted the world to hear.

The young impresario learned from his mistake, though, and for Small's next session he flew up a Jamaican legend named Ernest Ranglin and asked him to write the record's arrangement and to play guitar on it. Ranglin, something a musical god in his native Jamaica, would be the guy who most experts would eventually credit with creating the scratchy/high treble/reverb guitar sound that would serve as the linchpin of just about every reggae song ever recorded.

Ranglin stripped out the heavy sax Robinson had used in "Don't You Know" and pared back the guitar parts. This brought out both Small's high-energy vocals and the ska-flavored bass line. What's more, Blackwell had Ranglin tweak the arrangement to make "Lollipop" sound more like a traditional pop tune than a straight-forward ska number.

Ranglin stripped out the heavy sax Robinson had used in "Don't You Know" and pared back the guitar parts. This brought out both Small's high-energy vocals and the ska-flavored bass line. What's more, Blackwell had Ranglin tweak the arrangement to make "Lollipop" sound more like a traditional pop tune than a straight-forward ska number.

When it was finished and he listened to it on playback, Blackwell realized that "My Boy Lollipop" was the ska/pop hybrid record he'd been wanting to make from the beginning; a song with the potential to cross over and light the fuse on a massive ska craze in England and beyond.

Blackwell knew the song was going to be a big hit. He felt it in his bones. What he didn't know was whether or not his tiny Island Records had the resources to maximize its potential, especially overseas.

So what he did next, which was brilliant, was to license his new song out to a series of record companies across the globe, knowing that each company in each part of the world would have the financial motivation and wherewithal to give "My Boy Lollipop" the kind promotional and distribution muscle it would need.

The song was released worldwide in the late spring of 1964 -- just two months after the Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan -- and sold a million copies in just five weeks. But it didn't stop there. It became a #2 hit U.K., a #1 hit it Ireland, and a #2 hit in U.S. In fact, it went to either #1 or #2 in just about every country in which it was released, eventually selling a stunning 7 million copies worldwide.

What "My Boy Lollipop" did not do, however, was the one thing Blackwell had hoped it would most; namely, trigger an island music craze in the otherwise white record-buying public.

The problem was, due to the song's hybrid arrangement which muted much of its Jamiacan flavor, most fans viewed "My Boy Lollipop" not as some exotic new brand of island music, but as a simple, catchy pop tune. They looked beyond its ska rhythm and island vibe, and instead embraced the record for one reason: they liked it.

That, however, was the extent of the bad news for Blackwell; such as it was. "My Boy Lollipop" made millions for Island and positioned the company's president as no longer just some fringe player in the world of jazz, or some overly zealous advocate of island music. Instead, overnight he became the highly successful manager of an international pop star.

Within weeks the Island Record founder found himself getting calls and letters from people all over the world saying he needed to check out this singer or that band, most of them playing some combination of folk, pop or rock.

Ironically, one of the first such calls Blackwell received compelled him to jump a train for Birmingham, an hour or so north of London. He'd been told there was yet another 15-year old he needed to check out, and that he should do so quickly before some other record company snatched him up.

Ironically, one of the first such calls Blackwell received compelled him to jump a train for Birmingham, an hour or so north of London. He'd been told there was yet another 15-year old he needed to check out, and that he should do so quickly before some other record company snatched him up.

As Blackwell climbed the stairs to the third-floor nightclub, he heard a wailing, soulful voice that as it came into focus, literally, sent chills down his spine. When he got to the club level and went in, he saw onstage a rail-thin teenage kid sitting behind a massive Hammond B3 organ playing and belting out vintage R&B like no man Blackwell had ever seen or heard.

Little did he know it at the time, but his world -- and his company -- were both about to get much, much bigger.

Because when Blackwell signed that 15-year old kid, a skinny little musical genius named Stevie Winwood, and his band, the Spencer Davis Group (who signed with Blackwell almost solely on the strength of his success with "My Boy Lollipop"), he became more than just your average, garden-variety manager/producer.

Once Blackwell inked the Spencer Davis Group, he stopped being just some oddball Jamaican who people saw in clubs in flip-flops and island shirts. He was no longer just the tall, good looking surfer-type chap who somehow caught lightning in a bottle with that silly little pop tune of his.

After that trip to Birmingham, among the Carnaby Street mods, blues-worshiping dirty white boys and guitar-strumming, Dylan wanna-be's of the London music scene, Chris Blackwell's calling card became the fact he was Spencer Davis' manager.

Or more to the point, Steve Winwood's manager.

And to such budding and still-unsigned mega-talents like Keith Emerson, Ian Hunter, Brian Eno, Greg Lake, Robert Fripp, Ian Anderson, Bryan Ferry and Richard Thompson, to name just a few, that fact mattered. In fact, it mattered a lot.

Later that summer, Blackwell -- who by then had cemented his reputation as a guy with a savant-like ability with young talent -- traveled to New York for the 1964 World's Fair. The U.S. licensee of "Lollipop," Smash Records, had arranged August 12 to be declared "Millie Small Day" at the Fair, and for the plane flying Blackwell and Small from Germany, where they'd been touring, to be christened the "Lollipop Express."

It was at the World's Fair that Blackwell met another young singer from his native Jamaica. A few weeks later, Jimmy Cliff was added to Island Records' growing roster of musical acts.

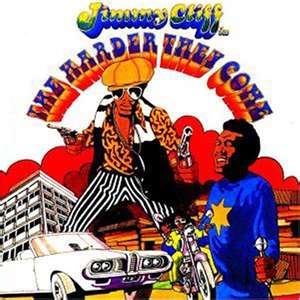

The Harder They Come

That proved to be another huge turning point, because when Cliff signed with the label, and less than a year later won the lead in a small but significant independent film called "The Harder They Come," everything changed for both Island and the music on which it was founded, an infectious hybrid of styles its growing number of fans were now calling reggae.

"The Harder They Come" told the fact-based story of a Kingston singer who, rather than signing away the rights to his music to a giant corporation, took up a life of crime selling marijuana, stealing and, when need be, killing. And while the story itself was compelling, what really tied the movie together was its soundtrack, which was anchored by Cliff's stirring title track.

"The Harder They Come" told the fact-based story of a Kingston singer who, rather than signing away the rights to his music to a giant corporation, took up a life of crime selling marijuana, stealing and, when need be, killing. And while the story itself was compelling, what really tied the movie together was its soundtrack, which was anchored by Cliff's stirring title track.

In it Cliff wrote and sang lines like: "But I'd rather be a free man in my grave, than living as a puppet or a slave."

Though "The Harder They Come" didn't make a dent in the box office when it was first released, it slowly gained momentum as it started playing on college campuses in Britain and the U.S., as well as on the late-night art-house circuit.

What the movie gave those college kids was context to the island music many found so utterly intoxicating. Suddenly, all those songs with the breezy, laid-back groove were about more than just sun-washed beaches, palm trees and getting high. They were about justice. They were about freedom. Reggae was suddenly about revolution, rising up from poverty and the fight for human dignity.

Slowly but surely the soundtrack, which Blackwell released on Island Records, become something of a sensation -- though it's impact was less about actual record sales than it was about reggae's growing influence on youth culture, both here and abroad.

For the first time since Blackwell started Island, the music of his mother country -- now referred to as reggae the world over -- not only had a name and a face, it had weight. And for the first time ever, it mattered.

But reggae was just one part of Island's rapidly expanding musical empire.

Around the same time, Blackwell signed an unknown British group named Free, whose lead singer Paul Rodgers, had one of the most powerful and evocative voices he'd ever heard. And within months, Free's first single "All Right Now" was skyrocketing up the charts in both the U.S. and the U.K., while at the same time making a deep and lasting impression on the growing underground radio movement.

Then a year later, Blackwell met a young pop tunesmith-turned-folkie in London named Cat Stevens, and helped him get out of his Decca contract so he could sign with Island and make the record he always hoped to make: a stripped-down, mostly acoustic album of all-original songs. That record, produced just as Blackwell promised it would be, became not only one of the most stunning musical achievements of the decade, but a huge commercial success; "Tea for the Tillerman."

Blackwell's working relationship with Jimmy Cliff then led him to yet another chance encounter and yet another seismic, game-changing contractual agreement. In 1971, while visiting Cliff on his native soil, Blackwell was introduced to a charismatic and incredibly talented young Rasta singer/songwriter. His name was Bob Marley. And just as he had done with Cliff, Blackwell quickly signed Marley and his band, the Wailers, to an exclusive deal with Island.

Within months, fueled by Marley's enormous talent, passion and sex appeal, Blackwell's uncanny musical instincts and marketing savvy, and the ever-growing popularity of "The Harder They Come," reggae suddenly exploded into a fireball of cultural influence, while at the same time becoming a full-fledged global phenomenon.

And because the two biggest names in reggae (Cliff and Marley) were on Island, Blackwell's company soon became synonymous with all aspects of Rasta culture -- while Marley found himself catapulted from local Jamaican hero to, quite literally, the most universally revered and iconic rock star in the world.

One More Coup

As his reputation for being a record executive willing to go to bat for his artists and give them what they needed to succeed began to grow, more and more established rock acts began making their way to Island from bigger and more profit-driven companies. One such artist who came to Blackwell in pursuit of more creative headroom was the L.A.-based troubadour Tom Waits, and Waits was soon followed by two other artists known for their clear sense of self, Melissa Etheridge and P.J. Harvey.

But poaching other labels for artists was not what Blackwell was about. He still loved finding and nurturing young talent, and to that end still had at least one more coup up his sleeve.

In 1980, he went out one night to a small club on the South End of London to hear a group of Irish kids that his A&R guy had been raving about. Though he resisted going initially, and didn't particularly like the band's music when he heard it ("sort of rinky dink," he'd later say), he absolutely loved their energy.

And he was especially taken with the passion and commanding presence of the group's lead singer -- a strutting rooster who called himself simply, Bono. So against his better judgment, Blackwell signed U2 to their very first recording contract.

And so it went; from Steve Winwood to Jimmy Cliff and Bob Marley, and on through Cat Stevens, Tom Waits, U2, Robert Palmer, Free, Emerson Lake & Palmer, Jethro Tull, Traffic, King Crimson, Mott the Hoople, the B 52's, Fairport Convention, Grace Jones, the Cranberries, Marianne Faithfull, P.J. Harvey, Toots and the Maytals, Tom Tom Club, Nick Drake, Sparks and Amy Winehouse, to name just a few.

In fact, to this day, Island Records -- which this year is celebrating its 50th anniversary -- remains, arguably, the single most influential and artistically sacrosanct record label in history.

And yet none of it would have been possible without the talent, energy and sparkle of a little teenage girl from Jamaica, not to mention a seemingly inconsequential little song she sang almost a half century ago about a teenage boy she called Lollipop.

A few other quick notes about "My Boy Lollipop:"

The success of Island Records clearly owes a great deal to Chris Blackwell's drive and ambition, not to mention his eye for young talent.

Likewise, it is very difficult to imagine Island growing as big or as quickly as it did if a teenage Steve Winwood hadn't signed that contract way back when, and in the process given Blackwell and his still-unproven label his tacit seal of approval.

But by Blackwell's own admission, all those things were secondary to the one person who truly set the wheels in motion for Island: little 15-year old Millie Small.

Say what you will about "My Boy Lollipop." Call it silly. Call it inane. Call it beach bubble gum. The fact is, the song's remarkable success left a musical legacy and helped shape the future of popular music like few songs ever have, or likely ever will.

Besides, as Blackwell has said time and time again, it was never really about the song. It was always about the singer. "The key really was Millie," Blackwell told NPR recently. "Everybody loved Millie."

So with that, please sit back, turn up the volume and enjoy M.C. Antil's Song of the Day for Thursday, December 30, 2010 -- a song that just might have been as historically significant as any in the history of rock and roll, Millie Small's "My Boy Lollipop."

Song: My Boy Lollipop

Artist: Millie Small

Composer: Robert Spencer, Johnny Roberts, Morris Levy

Year Released: 1964

Great stuff, M. Looking forward to all the 2011 goodies you have coming, and thank you for the 2010 gems.

A

M.- Loved the story and all the artists who signed with Blackwell. What ever happened to Millie?

Bruce

Bruce: Great question. Not sure. But curious minds want to know, huh? I'll have to check and let you know. Thnx for the feedback.