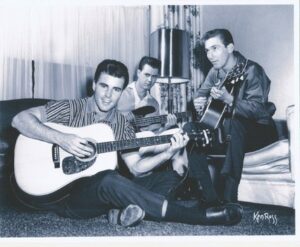

He and his buddy, a brilliant young picker named James, were two Louisiana teenagers from Shreveport who’d made a few records with their boyhood pal Dale Hawkins before heading west to seek whatever fame and fortune they could muster.

He and his buddy, a brilliant young picker named James, were two Louisiana teenagers from Shreveport who’d made a few records with their boyhood pal Dale Hawkins before heading west to seek whatever fame and fortune they could muster.

I’ll spare you all the machinations, but the important thing to know is that at a stop in Las Vegas, even though he’d never played the instrument in his life (and didn't even own one), Joe Osborn passed himself off as a bass player to country/rockabilly singer Bob Luman. As a result, he and his buddy, whose full name was James Burton, soon became the heart and soul of Luman’s band for the length of his run in Vegas, with Burton on lead and Osborn on bass.

Seeking even bigger and better things, after the Luman show closed, Osborn and Burton moved to L.A. where they were introduced to bandleader Ozzie Nelson who hired them for his son Ricky’s band, a rockabilly-flavored quartet that Nelson decided to feature on his weekly hit sitcom.

Seeking even bigger and better things, after the Luman show closed, Osborn and Burton moved to L.A. where they were introduced to bandleader Ozzie Nelson who hired them for his son Ricky’s band, a rockabilly-flavored quartet that Nelson decided to feature on his weekly hit sitcom.

Due in part to his exposure on the Ozzie and Harriet Show, Osborn’s lilting and melodic bass soon caught the ears of a few important music industry types in town, including red-hot producers Bones Howe and Lou Adler.

Adler, in particular, wanted someone to backup a new singer he’d recently signed, a reedy voiced Italian kid who'd adopted the name Johnny Rivers. The Beatles had exploded onto the scene and Adler wanted to do something a little different to try to re-capture the attention of American record buyers. The Whisky a Go-Go had just opened on L.A.'s Sunset Boulevard and his plan was to make a live recording of a Rivers appearance at the Whisky and release it as an LP. He hired Osborn as Rivers’ bass player.

The first single from that album, a rocking cover of Chuck Berry’s Memphis, Tennessee, was not only a hit, it did exactly what Alder hoped it might. Despite the mega-noise being generated by the Beatles, it managed to climb all the way to #2, fueled in part by some rhythmic (and live) audience hand-clapping and a throbbing bass line by Osborn. Engineering that night at the Whisky was Howe, who (like Adler) was about to break a major new singing group.

The first single from that album, a rocking cover of Chuck Berry’s Memphis, Tennessee, was not only a hit, it did exactly what Alder hoped it might. Despite the mega-noise being generated by the Beatles, it managed to climb all the way to #2, fueled in part by some rhythmic (and live) audience hand-clapping and a throbbing bass line by Osborn. Engineering that night at the Whisky was Howe, who (like Adler) was about to break a major new singing group.

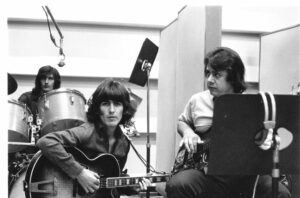

In Adler’s case, the group about to break consisted of four recently transplanted New York folk singers who called themselves the Mamas and the Papas. In Howe’s case, it was just about the whitest sounding bunch of black kids anyone in town had ever heard. Howe's kids called themselves the Fifth Dimension.

In both cases, both producers insisted on Osborn as their bass player. Within months of the cancellation of the Ozzie and Harriet Show Joe Osborn found himself appearing on every Mamas and Papas record and every Fifth Dimension record, along with every Johnny Rive rs record and even, still, a few stray Rick Nelson records.

rs record and even, still, a few stray Rick Nelson records.

Howe then immediately broke another new group, the Association, and he had Osborn playing on every Association recording as well.

Meanwhile, around that time, Osborn discovered (and was first to record) a brother and sister act, the latter of whom had a silky voice unlike anything he’d ever heard before. Pretty soon the Carpenters were dominating the charts and Joe Osborn was playing on every one of their records.

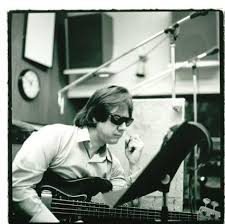

In time, demand was so intense for his melodic, darting bass lines that he doubled his hourly rate. Then he tripled it. However, all that seemed to do was stir even greater demand for his special talent.

In seemingly no time, he’d become the primary bassist for not just Rick Nelson, the Association, the Mamas and the Papas, Johnny Rivers and the Fifth Dimension, but also such Gary Lewis and the Playboys, Spanky and Our Gang, the Partridge Family, Laura Nyro, America, the Grass Roots, B.W. Stevenson, Barry Maguire, Simon & Garfunkel, Neil Diamond, the Monkees and Albert Hammond, to name but a few.

In seemingly no time, he’d become the primary bassist for not just Rick Nelson, the Association, the Mamas and the Papas, Johnny Rivers and the Fifth Dimension, but also such Gary Lewis and the Playboys, Spanky and Our Gang, the Partridge Family, Laura Nyro, America, the Grass Roots, B.W. Stevenson, Barry Maguire, Simon & Garfunkel, Neil Diamond, the Monkees and Albert Hammond, to name but a few.

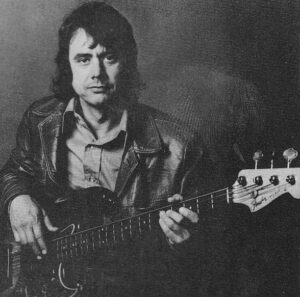

Joe Osborn eventually burned out on the frantic, nonstop recording, and in the early 80’s walked away from it all. He bought himself a little farm outside of Nashville and moved his family there to enjoy the solitude.

But he didn’t stop recording. To the contrary, after a brief respite, Nashville’s producers started calling him as well. And in short order, they too had fallen in love with Osborn's interchangeably driving and gentle bass lines and began booking him so regularly that by the end of the decade it was estimated he’d played on forty #1 country songs, providing a mix of bottom-end melody and throbbing rhythm for everyone from Kenny Rogers and Reba McIntire to Waylon Jennings, Merle Haggard, Lacy J. Dalton, Ricky Skaggs, John Conlee, Sylvia and Crystal Gayle.

(And that’s not forty Top 40 or even Top 10 country songs, mind you. That’s forty songs that climbed all the way to #1 on the country charts in a span of just over ten years.)

To say that Joe Osborn, literally, played the soundtrack of our lives is probably both an overstatement and an understatement -- and all at the same time. Because while there were plenty of world-class bass players being played on radio stations back in our salad days – people like Carol Kaye, Paul McCartney, James Jamerson, John Entwistle, Larry Graham, Willie Weeks and Duck Dunn – it was possible that if we heard fifteen Top 40 songs in a single hour between 1964 and 1974, as many as three or four of them might have featured Joe Osborn on bass.

To say that Joe Osborn, literally, played the soundtrack of our lives is probably both an overstatement and an understatement -- and all at the same time. Because while there were plenty of world-class bass players being played on radio stations back in our salad days – people like Carol Kaye, Paul McCartney, James Jamerson, John Entwistle, Larry Graham, Willie Weeks and Duck Dunn – it was possible that if we heard fifteen Top 40 songs in a single hour between 1964 and 1974, as many as three or four of them might have featured Joe Osborn on bass.

Joe Osborn died this week after a brief but hard battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 81. And news of his passing so moved me, and so compelled me to try to pay my respects, that I put everything on which I was working aside and attempted to briefly cobble together this woefully inadequate tribute to his remarkable gift.

But like so many great musicians who’ve passed since I've started this pop culture blog, rather than clutter up the page with words of feeble praise, I’d prefer to let their music speak for itself.

To that end, please enjoy this little sampler I’ve pieced together of some of Joe Osborn's more stunning (and perhaps lesser known) recorded moments. And while often a bass player is like an umpire in baseball – the better he is, the less you notice him – in the following six pop gems, Mr. Osborn’s bass steps into the limelight and becomes so prominent that the man’s melodic greatness can’t help but demand you stay focused on it.

To that end, please enjoy this little sampler I’ve pieced together of some of Joe Osborn's more stunning (and perhaps lesser known) recorded moments. And while often a bass player is like an umpire in baseball – the better he is, the less you notice him – in the following six pop gems, Mr. Osborn’s bass steps into the limelight and becomes so prominent that the man’s melodic greatness can’t help but demand you stay focused on it.

Enjoy, my friends. And, if you get a moment, please offer thanks today for one of the truly hidden figures behind the music of our lives; the incredible array of sounds and songs and stories that helped shape, if only in a small way, the man or woman you are today.

Everything that Touches You

The Association vastly overlooked Birthday album is pretty much the Joe Osborn show, as producer Bones Howe chose to showcase the man’s dancing and melodic bass to such an extent that, literally, it’s the very first thing you hear on just about every cut. This special recording of a special song is just one more example of Howe’s willingness to lead with his highest trump card, and do so from the opening song on Side A to the last cut on Side B.

Aquarius/Let the Sun Shine In

This medley of two different songs from the musical Hair, even as a single side of the same 45, remained two distinct songs; the first one languid and melodic, the second a good old-fashioned gospel hand-clapper. Originally, that same Bones Howe was going to record the two songs separately, since they were so vastly different, and piece them together. Osborn, however, suggested the musicians play the rhythm track straight through, at least once in rehearsal – which he and his fellow Wrecking Crew members did and, of course, nailed. But before laying it down, however, Howe pressed the intercom button, leaned forward, and said to Osborn and drummer Hal Blaine, “That was great, guys. But Joe, Hal, in the back half could you do what you just did, only, you know…more?” If you only listen to half this 45, make sure it’s the second one – the one on which Joe Osborn and his rhythm partner do, you know…more.

My Maria

Arguably, the coolest single of the 1970s was driven by, just maybe, that decade’s most understated and brazenly hip bass line. The whole song, that back in the day kicked down the doors on countless tinny radio speakers all across America with a lovesick yodel in its heart and hair on its brawny shoulders, did so on the wings of a Texas-sized groove unlike almost anything ever heard on Top 40 radio.

Tin Man

Listen to Osborn’s bass line elevate this mix of pretty melody and inane lyrics into something more meaningful than, perhaps, either deserves. That bass line you hear is the sound of four new radials barreling down a smooth stretch of blacktop, top down, radio blasting, and the wind blowing through that magnificent 70’s style mane of yours as though there was no tomorrow.

Out and About

There are any number of long-lost 60s singles that, even though they’ve fallen through the cracks of time, remain to this day touchstones of an era in which many of the finest musicians in America – people like Joe Osborn – were no longer sitting in orchestra pits, wearing rented tuxes and playing Brahms and Mozart. They were in L.A., chain smoking Lucky Strikes, downing bland, room-temperature coffee and getting paid scale to churn out some of the most wildly infectious commercial jingles and shimmering pop tunes the world has ever known.

Things I Should Have Said

See Out and About above and then, especially in light of the drum and bass fills on this one, ramp up everything I wrote by a factor of 50%.

Mississippi

If you can listen to Osborn’s bass in this little John Phillips gem and not be stirred by its power, rhythm and ability to drive the entire song Delta-bound like the Big Muddy herself, check your pulse. There’s a good chance you don’t have one.

Look to Your Soul

The song that a half century ago introduced yours truly to the greatest bass player you never knew, but heard time and time again. Close your eyes and listen, perhaps for the first time, to this one’s intro and, especially, its outro (beginning at the 2:35 mark). And as you do, please understand that what you’re listening to is not merely a bass line. It’s the very reason you’re reading this right now.

Rest in Peace, Joe. And Godspeed.