I was maybe 9 or 10 years old. My father was in the other room watching TV and called out excitedly, “Quick. Come in here. I want you to see something.”

I was maybe 9 or 10 years old. My father was in the other room watching TV and called out excitedly, “Quick. Come in here. I want you to see something.”

Just as I walked into the TV room, onscreen, comedian Jerry Lewis was likewise walking into a room. It looked like maybe an executive office, complete with all the trappings you might expect, including a well appointed conference table.

My dad wanted me to see a scene that captured his fancy when he first saw it at the theater two years prior. It was from the 1961 black-and-white film, The Errand Boy, a critical and commercial dud that Lewis wrote, directed and starred in, in which he plays a bumbling, low-level gofer at Paramount Pictures.

The next thing I knew I found myself sitting down to watch for the very first time one of the great moments in American humor, however small and otherwise inconsequential. It was a comedic bit not unlike Abbot and Costello’s Who’s on First or one of Belushi’s Samurai skits, a comedy routine that was a not a moment of comedic inspiration, but the byproduct of true comedic genius.

In the scene, Lewis sits at the head of the table, cigar in hand, and pantomimes a chairman addressing his fellow board members, lip syncing not so much actual words as the brassy sounds of the instruments in the big band number blaring beneath his pantomime.

In the scene, Lewis sits at the head of the table, cigar in hand, and pantomimes a chairman addressing his fellow board members, lip syncing not so much actual words as the brassy sounds of the instruments in the big band number blaring beneath his pantomime.

Apparently, during the production of The Errand Boy, Lewis’ co-writer, Bill Richmond, had no idea his partner planned to shoot the one-man scene he’d dreamed up the night before. He just showed up the following morning, a portable hi-fi in hand, and a Count Basie album from his own collection under his arm.

Lewis then put the record on and told the cinematographer where he would move and said to follow him.

A few takes later, followed by a few lighting tweaks, a camera move or two, and some post production work to overdub the tinny-sounding hi-fi version of Count Basie’s Blues in Hoss’ Flat with a full-throated, stereophonic one, a sliver of comedy film history found itself printed and in the can.

So a few days ago, following the news that Lewis passed at the age of 91, when a friend of mine, a trumpet player, jazz critic, and recovering dentist/lawyer, sent out a bulk email with the subject line, “Whether you liked him or not this bit was magic…”

I read that line and knew immediately not only who Michael was referring to, but where the link he enclosed would direct me. After all, there was no moment in Jerry Lewis’ long and uneven career that even came close to meriting such an exalted word as “magic.”

If you don’t believe me, watch for yourself.

My sense is Jerry Lewis was like most people you meet in life, a complex and sometimes confounding mix of emotions, neuroses and personality tics. The scene above, for example, like so much of the guy’s comedy (and, for that matter, even his work as ringmaster for the Muscular Dystrophy telethons he produced and starred in every Labor Day) seemed to indicate that just beneath the surface the man hid a palpable but very real (and perhaps very deep) sense of anger.

Just as the funniest clowns are often said to be hiding a deep sadness beneath their greasepaint, so too Lewis -- a clown of the first order -- constantly seemed to be in a life-and-death struggle with some undercurrent of anger, one that seemed to dwell just a pin-prick beneath his skin. It was as though some unreconciled and corrosive force was always gnawing at the man, a force that revealed itself time and time again throughout his career.

Just as the funniest clowns are often said to be hiding a deep sadness beneath their greasepaint, so too Lewis -- a clown of the first order -- constantly seemed to be in a life-and-death struggle with some undercurrent of anger, one that seemed to dwell just a pin-prick beneath his skin. It was as though some unreconciled and corrosive force was always gnawing at the man, a force that revealed itself time and time again throughout his career.

Perhaps the greatest example of this tug of war was a film Lewis wrote directed, and starred in two years after The Errand Boy, the ambitious but at times deeply unsettling comedy, The Nutty Professor.

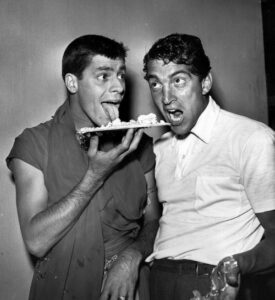

A modern retelling of the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde tale, The Nutty Professor had Lewis playing two roles, a nerdy professor – a character not so far removed from the mentally challenged man/child character he’d created during his meteoric rise as a nightclub comic, including his storied run with Dean Martin, and a role he could play in his sleep – and the virtual photo negative of that character, a crooning and ultra-suave hipster/lady-killer named Buddy Love.

Many thought that the uber-cool Love was a not-so-thinly disguised shot at his former partner, with whom he had an ugly and very public breakup. But in reality, Dean Martin had little or nothing to do with the creation of Buddy Love.

Many thought that the uber-cool Love was a not-so-thinly disguised shot at his former partner, with whom he had an ugly and very public breakup. But in reality, Dean Martin had little or nothing to do with the creation of Buddy Love.

The character – both characters in The Nutty Professor, in fact – were the two different (and at times antagonistic) sides of Lewis himself; the nerdy, insecure writer with the squeaky voice he’d always been, and the cold, unforgiving and emotionally aloof star he would eventually become.

And to be a ten year old kid and watch Buddy Love’s unhinged misogyny play out as he treated the Stella Stevens character – a young and coyishly sexy coed who was written as a case study in gentleness, warmth, and devotion – like something he’d just stepped in, was to understand for the first time in my young life the meaning of the phrase, “cringe-worthy.”

I felt that as a ten year old, and The Nutty Professor’s cringe-worthiness, at least for me, has only grown. Part of Buddy Love was the part of Jerry Lewis he allowed the world see, I sensed, even as I sat in that darkened theater years ago, popcorn in hand and my jaw slack. The other part was who Jerry Lewis really was -- or, just maybe, who Jerry Lewis might want to one day become.

That, to me, was the brilliance of Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy, an unflinching 1983 satire on the price and meaning of fame in America, a land whose cult-like obsession with celebrity has long since blossomed into an untethered and unseemly mania. The film captured the essence of Jerry Lewis as no other, before or since, and allowed him – for all intents and purposes, and perhaps for the first time in his life – to play himself.

And Lewis was just not memorable as the numbed-by-fame, emotionally shut down and cynical mega-celebrity/talk show host/kidnap victim. He was mesmerizing. That’s why, when any critic tries to list the greatest Oscar snubs in movie history, for my money any such list would have to start (and maybe even end) with Jerry Lewis’ sinfully unrecognized role in The King of Comedy, a dramatic turn by an almost invisible actor who not only didn’t win for his performance, but wasn’t even nominated.

And Lewis was just not memorable as the numbed-by-fame, emotionally shut down and cynical mega-celebrity/talk show host/kidnap victim. He was mesmerizing. That’s why, when any critic tries to list the greatest Oscar snubs in movie history, for my money any such list would have to start (and maybe even end) with Jerry Lewis’ sinfully unrecognized role in The King of Comedy, a dramatic turn by an almost invisible actor who not only didn’t win for his performance, but wasn’t even nominated.

By most accounts, when directing, Jerry Lewis could be a task master, especially when it came to certain actors and crew members. He was as demanding and exacting as he was insensitive, unfeeling, and, in the opinion of at least a few who were there, cruel. That’s why just a few years ago Vice magazine ran a profile of the man titled, “Jerry Lewis is Still Alive (and Still a Piece of Shit).”

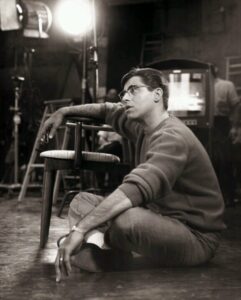

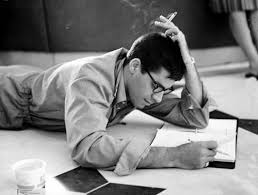

But make no mistake, Jerry Lewis was always, at least for the bulk of his adult life, an artist. A true and dedicated maker of art – comedic art for the most part, but art nevertheless. And the creative standards to which he held others in the making of it were the exact same ones to which he held himself.

But make no mistake, Jerry Lewis was always, at least for the bulk of his adult life, an artist. A true and dedicated maker of art – comedic art for the most part, but art nevertheless. And the creative standards to which he held others in the making of it were the exact same ones to which he held himself.

What’s more, just as great artists are constantly pushing the envelope, while picking, prodding and poking society's open wounds and most vulnerable areas, so too Jerry Lewis, especially young Lewis, was always exploring the darker side of who we are and often exposing us for who we think we are.

He had the artistic courage, for example, to create and inhabit a character like Buddy Love, an individual so vile and so fueled by cruelty, intimidation, and an almost sadistic disdain for his fellow man (and woman) that at times it seemed Lewis was daring his audience to try to like him.

He wrote and starred in The Bellboy, which was less a feature film than a daring and wildly experimental series of comedic skits shot on location in Miami’s Fontainebleau Hotel, in which the title character -- the heart and soul of the movie, mind you -- pantomimes virtually every moment of his screen time and does not say a single word until the very end.

Lewis even once wrote, directed and starred in a film in which he played a man in a World War II concentration camp, a broken-down, alcoholic German clown, jailed for getting drunk, baying at the moon, and making fun of der Fuhrer, and a guy whose life's mission, unbeknownst to his Nazi captors, soon becomes making the little Jewish children in the camp laugh before they're led to their execution. Martin poured his soul into the project, but apparently so hated how it was progressing that he suddenly and without warning stopped and never looked back. The Day the Clown Died now exists only in pieces in a vault in Paris somewhere, none of which, to date, have seen the light of day, much less been viewed by the public.

Lewis even once wrote, directed and starred in a film in which he played a man in a World War II concentration camp, a broken-down, alcoholic German clown, jailed for getting drunk, baying at the moon, and making fun of der Fuhrer, and a guy whose life's mission, unbeknownst to his Nazi captors, soon becomes making the little Jewish children in the camp laugh before they're led to their execution. Martin poured his soul into the project, but apparently so hated how it was progressing that he suddenly and without warning stopped and never looked back. The Day the Clown Died now exists only in pieces in a vault in Paris somewhere, none of which, to date, have seen the light of day, much less been viewed by the public.

Talk about pushing the envelope.

It’s interesting, in this country we’ve conspicuously made fun of the French because of the high regard in which they still hold Jerry Lewis. My sense is that’s because we’ve never understood what was behind that regard.

The French, for my mind, didn't love Jerry Lewis because of his film roles, or his television appearances, or – God forbid – his personality. They loved him because, in their mind, just like giants like Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton, he was so much more than just another filmmaker who happened to traffic in comedy. He was an auteur. An artist. And, as such, he tried to make those who saw his films reflect on themselves as much as he tried to make them laugh.

What the French -- in particular, great French filmmakers like Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Goddard -- understood about one of their own, something we Americans have yet to grasp, is that Jerry Lewis was never driven by money, acclaim or recognition. He was a creative and risk-taking storyteller fueled by an insatiable appetite for the truth, a filmmaker always willing to hold a mirror up to his audience and say, “Look. Now tell me honestly. What do you see?”

What the French -- in particular, great French filmmakers like Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Goddard -- understood about one of their own, something we Americans have yet to grasp, is that Jerry Lewis was never driven by money, acclaim or recognition. He was a creative and risk-taking storyteller fueled by an insatiable appetite for the truth, a filmmaker always willing to hold a mirror up to his audience and say, “Look. Now tell me honestly. What do you see?”

That is exactly what artists have always done for us, and why so many of them have died unrecognized or misunderstood, often right under our noses. Because when the bravest and most daring of them hold up a mirror, and we take a good hard (and honest) look at what we see, we don’t always like what we find.

I may not have loved Jerry Lewis or his brand of humor, especially as I got older, became more discriminating, and my taste in comedy grew edgier, more absurd and, for lack of a better word, more cerebral. And he was always low hanging fruit for my generation's satirists, one who became even more vulnerable the older and more out of touch he grew. Think of how many comedians over the years openly mocked the man and reduced his remarkable body of work to one single nasally, hyper-exaggerated and drawn out word, "Layyy-deeee!!!"

But then again, to be fair, in the later stages of his life, Jerry Lewis had become all but a living, breathing parody of himself.

But don’t for a minute think I didn’t respect the man's talent, his creative energy, or what he tried to reveal to us using little more than his imagination, his passion and, of course, his remarkable gifts as a clown. Because I did then, and I still do.

Godspeed, Mr. Lewis. And thank you. Really, I mean that. Thank you. For the laughs. For the zaniness. And above all, for the truth.

Godspeed, Mr. Lewis. And thank you. Really, I mean that. Thank you. For the laughs. For the zaniness. And above all, for the truth.

You, sir, were an artist. And as someone who first experienced your singular brand of genius one night when, as a young man, you grabbed my attention and clowned your way into my consciousness, if not my heart -- all without ever saying a word -- I will always remember you that way.