Susan Swain is one of those fiercely intelligent and incredibly wise people with whom, every so often in life, you're blessed to cross paths. (And if you’re thinking intelligent and wise are redundant there, you may just be one for whom store-bought knowledge and hard-fought wisdom are destined to run on parallel tracks.) Whatever, the simple fact is Susan Swain is a veritable rock star and the woman remains someone who, to this day, holds a special place in my heart and mind.

Susan Swain is one of those fiercely intelligent and incredibly wise people with whom, every so often in life, you're blessed to cross paths. (And if you’re thinking intelligent and wise are redundant there, you may just be one for whom store-bought knowledge and hard-fought wisdom are destined to run on parallel tracks.) Whatever, the simple fact is Susan Swain is a veritable rock star and the woman remains someone who, to this day, holds a special place in my heart and mind.

Anyway, it was a cable industry trade show in 1995 or ’96 (I believe, maybe, the Western Show in Anaheim). And I happened to stop by the C-SPAN booth, where I’d gone to say hi to my friend, who was an EVP at C-SPAN at the time, but who would soon become co-CEO. Even though she and I both lived and worked in the DC area, and her house was no more than a stone’s throw from my office in Old Town Alexandria, it was only at trade events like the Western Show that we really got a chance to talk or spend any time together.

I remember as Susan and I were chatting that day, she happened to notice over my shoulder the line at the booth across the way had grown to at least 100 yards long and started to snake around the exhibit floor. What’s more, a buzz began emanating from those elbowing their way nearer and nearer to what turned out to be Classic Sports Network's booth -- so much so, in fact, you could almost feel that buzz on your skin.

I remember as Susan and I were chatting that day, she happened to notice over my shoulder the line at the booth across the way had grown to at least 100 yards long and started to snake around the exhibit floor. What’s more, a buzz began emanating from those elbowing their way nearer and nearer to what turned out to be Classic Sports Network's booth -- so much so, in fact, you could almost feel that buzz on your skin.

“What the heck is going on,” Susan asked almost rhetorically, her brow furrowing and a little half-smile of uncertainty forming on her face.

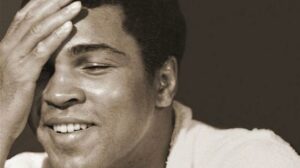

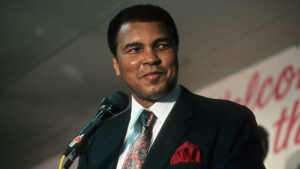

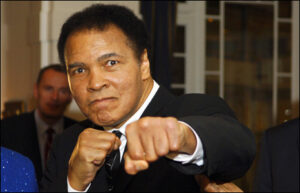

I looked over and at the front of the line saw an unimposing but well-dressed African American man, round-shouldered, slightly hunched over, and seated in a director’s chair perched on a small riser. He was surrounded by a handful of low-level Classic Sports employees, one of whom had an instamatic camera and was taking grip-and-grin shots of him shaking hands and posing, one by one, with each person in line.

“Oh my God,” I gasped slightly, my breath collapsing inward. “That’s Muhammad Ali.”

“So?” Susan asked, this time not the least bit rhetorically.

“So?” Susan asked, this time not the least bit rhetorically.

“Are you kidding me?” I said. “Muhammad Ali? I’m mean, the guy is up there with the likes of, I don’t know, maybe Gandhi, Churchill and FDR. Seriously, Susan, you watch. History’s gonna remember Ali as one of the most charismatic world leaders of the 20th Century.”

“Get outta here,” she said. “Are you kidding me? Muhammad Ali?”

Now, understand, as one of the most well-read and well-prepared interviewers in the history of television, not to mention a published author in her own right, Susan Swain has likely forgotten more history than most will ever know.

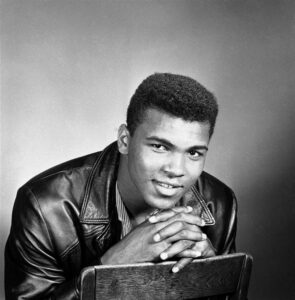

“C’mon. Follow me,” I said, taking her by the elbow and making a beeline for the tail end of the queue. And there, while waiting in line for the next who-knows-how-many-minutes, I proceeded to tell my friend all I knew about Ali’s transformation from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali and his one-man crusade against being drafted at the height (or maybe depth) of the Vietnam War.

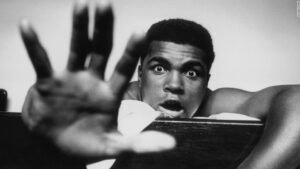

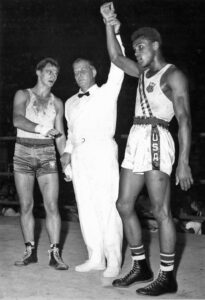

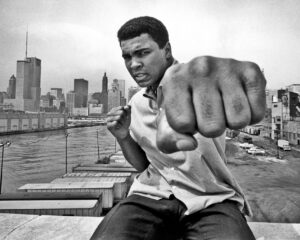

I told her about how, as an amateur, young Cassius Clay had shocked the world during the 1960 Olympics by out-quicking, out-smarting and thoroughly out-boxing the imposing and powerful de facto pro boxers from such dreaded Soviet block countries as the USSR and East Germany, and how he’d brought back the gold to the U.S. at the height of the Cold War and at a time no one even knew the kid's name.

I told her about how, as an amateur, young Cassius Clay had shocked the world during the 1960 Olympics by out-quicking, out-smarting and thoroughly out-boxing the imposing and powerful de facto pro boxers from such dreaded Soviet block countries as the USSR and East Germany, and how he’d brought back the gold to the U.S. at the height of the Cold War and at a time no one even knew the kid's name.

I told her too how, when he got home and early on was refused service in a small roadside diner near his home in Kentucky, he was so deeply hurt and so upset he immediately went to a bridge and threw his medal into the water below.

But mostly I told her how he had been drafted at the peak of his fame and power, when he was the undefeated and unrivaled heavyweight champion of the world, and how he refused to be inducted, arguing that as a Muslim (he’d converted and changed his name a year or so prior) the Vietnam conflict was not his war.

Maybe the memory of that diner was still front-and-center in his mind, I said. Who knows? But for whatever reason, Ali dove headfirst into his name change and new religion and refused to get inducted or serve in Vietnam, explaining over and over to an increasingly skeptical, antagonistic and divided press corps that he had nothing against the Vietcong.

“They never called me nigger, they never lynched me,” he said. “They didn't put no dogs on me,” an above-the-fold quote that only fanned the growing flames of public hue and cry in opposition to his stance.

But the thing was, I explained to her, Ali didn’t need to go through any of that. Hell, just like Joe Louis in World War II, he could have simply joined the Army and served his time doing a cushy job that likely would have had to do more with photo ops than live combat. It’s not like they were going to send the guy to the front lines, I said. They would have had him doing token deskwork for a few hours a day, far from danger. Hell, he might have even been stationed stateside for all we know.

But the thing was, I explained to her, Ali didn’t need to go through any of that. Hell, just like Joe Louis in World War II, he could have simply joined the Army and served his time doing a cushy job that likely would have had to do more with photo ops than live combat. It’s not like they were going to send the guy to the front lines, I said. They would have had him doing token deskwork for a few hours a day, far from danger. Hell, he might have even been stationed stateside for all we know.

He could have continued training and stayed in top fighting shape. He could have helped the Army stage boxing exhibitions and fundraisers. And, above all, he could have been the poster child of the exact kind of dog-and-pony PR effort the Army brass needed as, faster and faster, the war in Southeast Asia began spiraling out of their control.

In fact, I said, Ali probably could have even continued defending his title, even in the Army. But the guy’s conscience just wouldn’t let him. His sense of right-and-wrong was so profound and his inner voice so strong, he couldn’t bring himself to take the easy way. So, he dug in his heels and did it the hard way. Against all logic, reason and counsel, the guy took a stand.

He was then arrested, found guilty and sentenced to five years in prison. Worst of all, he was stripped of his title and not permitted to box professionally for three full years – the only thing he knew how to do, mind you, to earn a living.

He was then arrested, found guilty and sentenced to five years in prison. Worst of all, he was stripped of his title and not permitted to box professionally for three full years – the only thing he knew how to do, mind you, to earn a living.

“But you need to understand, Susan,” I said, “Ali was doing this when Americans everywhere, young and old, rich and poor, Republican and Democrat, were starting to question Vietnam and whether or not, unlike past wars, we were actually on the moral high ground this time around.”

But there’s a big difference, I explained, between burning a draft card or holding a picket sign and giving up tens of millions of dollars out of your own pocket – in 1969-era money, mind you, during your prime earning years – because your beliefs are so resolute. “Now that,” I said, “is what I call standing on principle.”

I then explained there was a new documentary on Ali’s legendary “Rumble in the Jungle” with George Foreman that was just being released, and that the movie is in limited distribution in a few cities around the country, including Washington. “When we get back home,” I said, “I’ll take you.”

And that’s exactly what we did. And if you’ve not seen When We Were Kings, I urge you to do so. The documentary captures perfectly not only Ali’s almost indescribable talents, gravitas and instincts as a boxer and showman, but the essence of his savant-like ability to inspire, touch and act as a sort of moral bellwether for almost anyone fortunate enough to cross his path.

And that’s exactly what we did. And if you’ve not seen When We Were Kings, I urge you to do so. The documentary captures perfectly not only Ali’s almost indescribable talents, gravitas and instincts as a boxer and showman, but the essence of his savant-like ability to inspire, touch and act as a sort of moral bellwether for almost anyone fortunate enough to cross his path.

And as you’re watching When We Were Kings, you may slowly come to realize, as I did, that in an era during which hippies were espousing free love and engaging in group “love-ins,” the age of Aquarius was supposedly ushering in an era of peace, harmony and understanding, and Coke was cynically lining its pockets by singing about brotherhood and implying this world would be a better place if people of all cultures just bought each other a little more caramel colored sugar water, here was a man – a deeply principled man – not just talking about peace and love, but actually living it. What’s more, he was willingly placing himself on the sacrificial altar on behalf of his beliefs.

You may realize, as I did watching the film, the extent to which Ali’s greatest purpose in life – and his ultimate legacy – was not at all tied to what he did to people inside the ring. It was tied to what he did to them outside it.

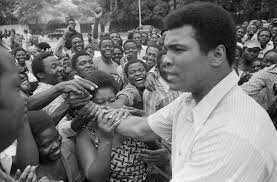

He showed the world – and I mean the entire world, regardless of color, ethnic makeup or religious leaning – what it means (and what it takes) to really, truly love your fellow man. The black, largely uneducated kid from the poorest section of Louisville loved people everywhere, and truly believed this crazy, constantly warring world of ours was big enough, smart enough and understanding enough for all people, all ideologies, and all cultures to bury their differences and somehow live in harmony.

He showed the world – and I mean the entire world, regardless of color, ethnic makeup or religious leaning – what it means (and what it takes) to really, truly love your fellow man. The black, largely uneducated kid from the poorest section of Louisville loved people everywhere, and truly believed this crazy, constantly warring world of ours was big enough, smart enough and understanding enough for all people, all ideologies, and all cultures to bury their differences and somehow live in harmony.

Plus, the man was an absolute freak when it came to being able to distill the biggest and most complex problems down to simple concepts using a handful of words, often rhyming ones. At one point in When We Were Kings, a day or two before he’s about to depart for Zaire, Ali is asked by an African American TV journalist if he had anything he’d like to say to the young people of America (with the gentle subtext of the question being, does he have anything to say to the young black people of America?).

Yeah, said Ali, looking straight in the camera, playful yet serious-as-a-heart-attack, stay off dope and brush your teeth. That’s it. That’s all. Just those two things.

Stay off dope. Brush your teeth.

Stay off dope. Brush your teeth.

Think about that; what a heartfelt and borderline genius kernel of wisdom for any young person living in urban poverty in the troubled 70s to hear, when almost daily the country seemed to take one more step downward toward a cesspool of uncertainty, decay and social unrest. Give most world leaders, black or white, weeks to prepare an answer to that one and I guarantee you none would come up with anything nearly so simple yet profound.

At another point in the film, author George Plimpton, who was in Zaire that night to cover the fight for Esquire, argues that while it's long been held the shortest poem in the English language is Fleas, which reads simply, “Adam had ‘em,” that is no longer the case. The author says Ali has a poem that’s even shorter, one that speaks to the essence of who the man is, and what he believes. It goes simply, says Plimpton, “You. Me. We.”

Afterwards, after a number of lettered and often eloquent talking heads like Plimpton and one-time boxer Norman Mailer had put Ali and his stunning victory in historic (and almost poetic) terms, and while the credits rolled behind us, Susan, walking up the aisle to my left, said to no one in particular except perhaps herself, “Wow. I get it now.”

But back to Anaheim.

By the time we’d waited 20 or so minutes, and by the time we'd finally inched our way to the on-deck circle for our sliver of face time and a photo op with the former champ, Susan said she wanted me to go first. I asked, “Are you sure?” “Yep,” was all she said.

By the time we’d waited 20 or so minutes, and by the time we'd finally inched our way to the on-deck circle for our sliver of face time and a photo op with the former champ, Susan said she wanted me to go first. I asked, “Are you sure?” “Yep,” was all she said.

I said OK. But as I stood there, and as I watched the physically crumbling former champ, who as a young, strutting buck floated like a butterfly and declared himself “the Greatest,” take yet another Polaroid with yet another star-struck cable person, it occurred to me I didn’t give a damn about a stupid picture. I had something more important to do. I had something personal I wanted to tell the man.

So when my turn came and I stepped up on the riser, and when the young lady tried to coach me where to stand and told me to look her way, smile, and shake Ali’s hand, I broke ranks. “I’m sorry, Miss, I don’t really care about a picture,” I told her, gently but firmly. “Please, feel free to take whatever shot you want. I just have something to say to the Champ.” I then leaned over and offered Ali my hand. His massive trembling meathook caught mine halfway and enveloped it. I grabbed back and leaned in a little closer.

“Champ,” I said in a half-whisper (and I’m paraphrasing here), “I just have something quick to tell you. On behalf of so many guys my age – guys who, like me, were at one point just impressionable, snot-nosed kids looking for someone, anyone, in that crazy era we grew up in to come forward and show us how to stand up for what you believe in, and how to act on principle, regardless of the consequences – I just want to thank you for being that guy. The courage you showed in staying true to yourself changed us forever – changed me forever – and I just wanted to tell you I’m not sure I’d be the man I am today without you or what you taught me.”

“Champ,” I said in a half-whisper (and I’m paraphrasing here), “I just have something quick to tell you. On behalf of so many guys my age – guys who, like me, were at one point just impressionable, snot-nosed kids looking for someone, anyone, in that crazy era we grew up in to come forward and show us how to stand up for what you believe in, and how to act on principle, regardless of the consequences – I just want to thank you for being that guy. The courage you showed in staying true to yourself changed us forever – changed me forever – and I just wanted to tell you I’m not sure I’d be the man I am today without you or what you taught me.”

He looked at me for a moment, his right hand still clinging to mine, as I continued to hunch over him, in part to keep others from overhearing, even Susan. And when I was done, Muhammad Ali just stared at me for what was likely only a second or two, but felt like an eternity.

Then – and I mean this from the bottom of my heart – his eyes began to tear up. And what I saw staring back at me through those moist pools was the soul of one of the most remarkable men this world has ever known, a wounded martyr whose combination of pride and pain was there for me to see, if only for a moment, reflected in his eyes. Then with his left hand, its once-otherworldly speed and dexterity reduced to a random series of tics and spasms, Ali cupped the back of my neck and pulled me forward. He then turned toward me and kissed me softly on the cheek, his head shaking gently as he did.

Then – and I mean this from the bottom of my heart – his eyes began to tear up. And what I saw staring back at me through those moist pools was the soul of one of the most remarkable men this world has ever known, a wounded martyr whose combination of pride and pain was there for me to see, if only for a moment, reflected in his eyes. Then with his left hand, its once-otherworldly speed and dexterity reduced to a random series of tics and spasms, Ali cupped the back of my neck and pulled me forward. He then turned toward me and kissed me softly on the cheek, his head shaking gently as he did.

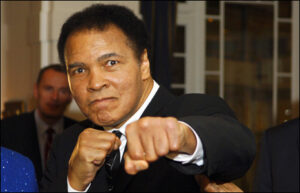

But almost as soon as he’d done that – bam – the greatest athlete of my lifetime, and maybe all time, released my neck and unloosed his fingers, bringing to an abrupt end both our handshake and the moment. He then made two giant fists and, hands still quivering, feigned like he was sparring with me, his eyes twinkling again and a devious smile creeping across his lips, while the playfulness that many would come to realize was as much a cover as a trademark revealed itself in all its blazing glory.

And while he never said a single word, when our time together had run its course I stood back up, my eyes wide and fixed squarely on his, and said the only thing that came to mind: “I’ll never forget this.”

And while he never said a single word, when our time together had run its course I stood back up, my eyes wide and fixed squarely on his, and said the only thing that came to mind: “I’ll never forget this.”

And I never have.

Good night, Champ. Here’s to you. And here’s to what your remarkable humanity so long ago taught so many my age not only about ourselves, but more importantly, about each other. The world, indeed, is a slightly colder place without you, even the older and more brittle version you eventually became.

But thanks to how you lived, and especially how you fought, both in and out of the ring, we will all spend the rest of our lives believing – as you showed us time and time again – in the dignity, the nobility, and the brotherhood of our fellow man, and we will all have at least one thing to keep us warm.

But thanks to how you lived, and especially how you fought, both in and out of the ring, we will all spend the rest of our lives believing – as you showed us time and time again – in the dignity, the nobility, and the brotherhood of our fellow man, and we will all have at least one thing to keep us warm.

Our memories of you and your incredible fire.