To a 14-year old part-time busboy and dish-washer, he wasn’t Carmen Basilio, the former Middleweight Champ. He was Carmen Basilio, the funny guy who always talked like he had a cold, the guy with those gnarled features and that slightly humorous face, at the center of which was a nose that could have been plucked off a vine somewhere, and the guy from whom we at Norm’s Restaurant used to buy all our Italian sausage – both, of course, the link and the patty style.

To a 14-year old part-time busboy and dish-washer, he wasn’t Carmen Basilio, the former Middleweight Champ. He was Carmen Basilio, the funny guy who always talked like he had a cold, the guy with those gnarled features and that slightly humorous face, at the center of which was a nose that could have been plucked off a vine somewhere, and the guy from whom we at Norm’s Restaurant used to buy all our Italian sausage – both, of course, the link and the patty style.

Hell, I still see those long, rectangular white boxes of Carmen’s hot and sweet sausages like it was yesterday, all stacked high in Norm’s walk-in, and all featuring that silhouette of Carmen on top, him in his gloves and trunks, lean and mean, crouched low, coiled and ready to strike.

It was the late 1960s, probably ’68 or ’69, and it was the New York State Fairgrounds; the sprawling and cavernous but rickety old Horticultural Building, to be exact. And Norm was Norm Rothschild, an old-school restaurateur, one-time fight promoter and arguably the single most decent, honest and hard-working man I’d ever met in my life – before or since.

Among the many things I loved about Norm’s during Fair Week was being able to watch the parade of boxing big-wigs, wanna-bes and hangers-on that always seemed to drop by to say hi to Norm and Ada, most of them from the fringes of that sport’s golden age.

I won’t get into much of that, since that’s not my point today. But I have to tell you I would just love as a kid being a fly on the kitchen wall as people like Norm, Carmen and the boxing brothers Ralph, Mike, Joey and Johnny DeJohn, the last of whom became Carmen’s manager, traded one fight story after another, often about some of the biggest boxing names from the 40s and 50s, legendary pugilists I’d heard and maybe even read a bit about. People like Sugar Ray Robinson, Kid Gavilan and the two Rockys; Marciano and Graziano.

I won’t get into much of that, since that’s not my point today. But I have to tell you I would just love as a kid being a fly on the kitchen wall as people like Norm, Carmen and the boxing brothers Ralph, Mike, Joey and Johnny DeJohn, the last of whom became Carmen’s manager, traded one fight story after another, often about some of the biggest boxing names from the 40s and 50s, legendary pugilists I’d heard and maybe even read a bit about. People like Sugar Ray Robinson, Kid Gavilan and the two Rockys; Marciano and Graziano.

Carmen, of course, was a muck-lander, a guy from Canastota, about 20 miles to the east of my hometown of Syracuse; a place known for its low, flat soggy farmland – a type of soil my farm girl of a grandmother and her family used to call “muck land ” – which in agrarian circles is apparently perfect for growing two things: potatoes and onions. In fact, Carm’s father, an Italian immigrant, was able to feed and clothe ten kids and a wife on what he made working on a Canastota onion farm.

Norm, meanwhile, was the young enterprising businessman, politician and promoter who saw Carmen’s championship potential way back when he was still a 20-something club fighter and began arranging and promoting professional fights for him around the country, including, eventually, a few of his title bouts.

I bring all this up only because when I heard Carmen passed away this past month at the age of 85, it gave me pause. Real pause. But not for the reason you’d think.

When I reflected on the Carmen Basilio I knew, if only slightly, I didn’t think of that big lumpy nose of his, or that mug which seemed to come straight out of Central Casting, or even those six-to-a-pound sausages he used to peddle. I didn’t think of his funny stories, his parade of boxing cronies, his G-rated humor, or his gentle nature and disarming warmth and humility. Hell, I didn’t even think of those wonderful nights I spent as a fly on the wall in Norm’s kitchen so many summers ago.

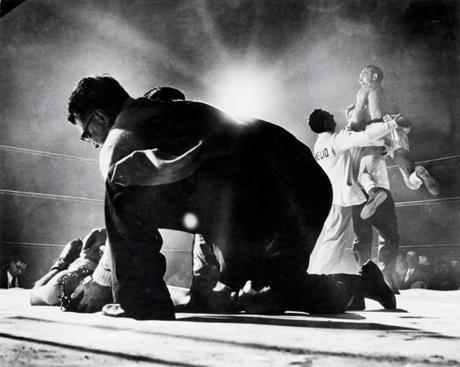

I thought of a picture. A single photographic image. I thought of one almost-perfect moment in Carmen’s boxing life that had been captured on film; a shot I had never, ever had the occasion to see – until, that is, I was probably 45; a stunning black-and-white image that for my money and from what I can tell, may just be the single most dramatic, lyric and well-composed sports photograph any man had ever taken.

I thought of a picture. A single photographic image. I thought of one almost-perfect moment in Carmen’s boxing life that had been captured on film; a shot I had never, ever had the occasion to see – until, that is, I was probably 45; a stunning black-and-white image that for my money and from what I can tell, may just be the single most dramatic, lyric and well-composed sports photograph any man had ever taken.

And while I have since bonded to the image, in part because I sorta knew one of the guys in it – two of them actually – my real love of it continues to run far deeper than that.

The photo flat out moves me. I mean that; and sometimes to tears. It’s that incredible.

It is a photo that in many ways distills the very essence of why sports, for all its mindless, ESPN-idolizing, boo-yah shouting, stat-spewing and chest-beating frat-boy mindlessness, still has the ability to every now and then draw me in like a siren’s song.

It is a photo which exhibits why, in no uncertain terms, when done right and in the hands of an artist, photography can still tell a story like no other medium in the world.

The shot was taken by a hard-working journalist and shutterbug named Hy Peskin, who at the time was toting credentials for Sports Illustrated. The year was 1955, the setting was the old Boston Garden, and the event was the re-match for the Welterweight Championship of the World between Carmen and Tony DeMarco, a powerful Italian slugger with thunder in his right hand, and a kid who grew up on the mean streets of that city’s North Side.

The shot was taken by a hard-working journalist and shutterbug named Hy Peskin, who at the time was toting credentials for Sports Illustrated. The year was 1955, the setting was the old Boston Garden, and the event was the re-match for the Welterweight Championship of the World between Carmen and Tony DeMarco, a powerful Italian slugger with thunder in his right hand, and a kid who grew up on the mean streets of that city’s North Side.

Basilio had beaten DeMarco just a few months earlier in Syracuse, but about halfway through their scheduled 15-round rematch DeMarco began pouring it on the champ, pounding away at Basilio’s small, wiry frame. By the end of the 8th, all three judges had the more powerful challenger comfortably ahead on points, and sensing that, the crowd at ringside began taunting Basilio, shouting out what his trainer Angelo Dundee soon realized had become clearly evident; the only way for his ring-smart but modestly talented muck-lander to retain his title would be to knock Boston’s favorite son out cold, something that was going to be easier said than done – especially in his home arena, his hometown Gah-den.

So in the 9th, per instructions from Dundee, Carmen came out and started wailing on DeMarco’s mid-section, throwing caution to the wind and pulverizing his opponent’s torso with a relentless succession of jabs and uppercuts. Soon DeMarco began slowing down and then almost stopped moving altogether, except perhaps in slow motion. What’s more, his punches no longer had either their thunder, or their cat-like quickness. They were leaden and hollow, deliberate and telegraphed.

So in the 9th, per instructions from Dundee, Carmen came out and started wailing on DeMarco’s mid-section, throwing caution to the wind and pulverizing his opponent’s torso with a relentless succession of jabs and uppercuts. Soon DeMarco began slowing down and then almost stopped moving altogether, except perhaps in slow motion. What’s more, his punches no longer had either their thunder, or their cat-like quickness. They were leaden and hollow, deliberate and telegraphed.

By the 12th, the champ had completely taken charge and was now moving in for the kill. Never known as a knockout puncher – his talent was more in taking powerful punches than giving them – the kid from Canastota still knew he needed to try to knock DeMarco out to win. Which is exactly what he did. First a left, then a right to the face, then another hard left to the ribs, and then finally a haymaker of a right, seemingly delivered from somewhere around the third or fourth row. DeMarco took a step forward, buckled and then crumpled like a heap onto the canvas, crashing into referee Mel Manning on the way down, before coming to rest crucifixion-style – head to one side, eyes closed, mouth open and arms limp by his side.

That’s when Peskin struck. And what resulted was the picture you see above.

That’s when Peskin struck. And what resulted was the picture you see above.

From Peskin’s ring-level perspective, he chose to focus not on DeMarco, or even Basilio. He instead aimed his lens squarely at Manning and placed the referee and one of DeMarco’s corner men who'd sprinted across the ring to come to the aid of his fighter nearly dead center. And at the instant he took the shot he caught both men one knee looking down on the vanquished DeMarco, as though in prayer. And below them lay the battered challenger, bloody, sweaty and completely still, a hand gently cradling his head.

And prayer seems appropriate, because the moment and the image seem more spiritual than temporal; more suited for, say, a house of worship than the pages of a sports weekly. After all, the longer you look the more the religious imagery begins to deluge you. There’s DeMarco, the fallen martyr. There’s Basilio leaping skyward into DeJohn’s arms, as if carried away by the rapture. There’s the saintly Good Samaritan down on one knee, reaching out his hand to his fellow man, himself wrapped in a halo of compassion. And, of course, there, smack dab center, is the heavenly light, radiating in all directions, its brilliance warming, protecting, illuminating and even beckoning those present.

The unfortunately small size of the copy you see on this page robs the photo of so much of its power, as does the fact that what you're looking at is basically a digital copy of a copy of a print. But hopefully you get the idea.  It’s a stunning photograph from a long-forgotten photographer that somehow never received its due. Yet the image has never lost one ounce of its ability to knock me to the canvas like a roundhouse right.

It’s a stunning photograph from a long-forgotten photographer that somehow never received its due. Yet the image has never lost one ounce of its ability to knock me to the canvas like a roundhouse right.

That’s what I thought about when I heard Carmen Basilio had died last month. That’s what flashed in my mind. And, more than my thoughts, that's what I wanted to share with you today.