Over the course of the past few years, many pop music insiders, fans and geeks have done their best to label them as the Wrecking Crew; the stable of ferociously talented studio musicians and sidemen that producers Quincy Jones, Phil Spector, Lou Adler, Lee Hazelwood, Brian Wilson and their ilk used to regularly use on various projects and sessions in the 1960s, and who served as the guitarists, bassists, drummers, keyboardists, string players, reed players, percussionists and others on what would become, in many ways, the audio track of an entire generation.

Over the course of the past few years, many pop music insiders, fans and geeks have done their best to label them as the Wrecking Crew; the stable of ferociously talented studio musicians and sidemen that producers Quincy Jones, Phil Spector, Lou Adler, Lee Hazelwood, Brian Wilson and their ilk used to regularly use on various projects and sessions in the 1960s, and who served as the guitarists, bassists, drummers, keyboardists, string players, reed players, percussionists and others on what would become, in many ways, the audio track of an entire generation.

But all attempts at after-the-fact branding aside, this stable of men and (even a few) women who played on so many hit songs saw themselves at the time – and perhaps even now – as little more than hard-working, card-carrying members of Local 47, the local chapter of the musicians union in Los Angeles, a local which at the time listed some 17,000 dues-paying members, and counting.

By the spring of 1964, Beatlemania and what was being referred to as the “British Invasion” had fundamentally changed the industry’s opinion of not only the kind of records that should be made in America, but perhaps more significantly where those records should be made. Consider; on the final day of 1963, just five weeks before the Beatles appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, a quick study of the Billboard pop charts revealed that half the records that hit the top of the U.S. pop charts that year had been recorded in New York, three of them in L.A., and none in London.

Just one year later, records made in London held the top spot in the U.S. for a stunning 23 out of 52 weeks, while New York-based records slipped to 12, and L.A. held firm with three.

By 1965, however, things in the U.S. literally found themselves turned upside down. While a London-based record managed to hold the top spot on the American charts for a still-astounding 23 weeks that year, Los Angeles skyrocketed to 20 weeks. Meanwhile, Hang on Sloopy by the McCoys emerged as the only record made in New York the entire year to reach #1.

By 1965, however, things in the U.S. literally found themselves turned upside down. While a London-based record managed to hold the top spot on the American charts for a still-astounding 23 weeks that year, Los Angeles skyrocketed to 20 weeks. Meanwhile, Hang on Sloopy by the McCoys emerged as the only record made in New York the entire year to reach #1.

What’s more, by 1965 such Brill Building stalwarts as Spector, Don Kirshner, Neil Diamond, Neil Sedaka, Gene Pitney and Howard Greenfield, to name just a few, along with the productive and ever-reliable songwriting teams of Barry Mann & Cynthia Weil, Gerry Goffin & Carole King and Jeff Barry & Ellie Greenwich had all pulled up stakes, put New York in their rear-view mirrors, and headed for points west. It was almost as through a giant pair of hands shook the continent and anyone, anywhere with a gift for writing, producing and/or playing a two and a half minute pop song was suddenly rolling westward toward the palm-lined streets, eternal sunshine and roaring surf of L.A.

Some critics like to call the Sixties the Decade of the Singer/Songwriter, thanks to influential, often brilliant troubadours like Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Donovan, Diamond and others, along with, of course, the growing number of self-reliant bands who wrote their own material, like the Beatles, Stones, Beach Boys, Lovin’ Spoonful, Rascals, Kinks and Who.

Some even consider it the Decade of the Producer, thanks in large part to such control room control freaks and recording session autocrats as Spector, Adler, Hazelwood and Jones.

Some even consider it the Decade of the Producer, thanks in large part to such control room control freaks and recording session autocrats as Spector, Adler, Hazelwood and Jones.

But while I suppose one could easily make a case for either, for my money that ten-year stretch – and especially the final five years – was the Decade of the Sideman.

Because in that relatively brief period of time, the session musician moved front and center in American pop music and began adding a level of craftsmanship and even brilliance to even the most insignificant pop tune. And as a result, there reached a point in the ‘60s, seemingly overnight, when many bands and artists that could play their own instruments were no longer allowed to. Session players, many of whom saw themselves as little more than tradesmen, were being called on the play the songs, while the recording artists whose name appeared on the label were only being asked to sing them.

And let’s be honest; for all the myopic, deeply misguided and incredibly short-sighted decisions record executives were to make over the next 50 years, one would remain hard pressed to find fault with their decision to use sidemen to the extent that they did in the ‘60s. Those corner office suits, big-money impresarios and iron-fisted record-makers had, literally, the industry’s crème of the crème at their disposal and could hire some of the most talented, brilliant musicians in the world by merely picking up the phone and summoning them, knowing full well that such players would be tuned and ready to go in a few hours’ notice.

So why, in god’s name, not use them?

So why, in god’s name, not use them?

But it wasn’t just pop records those union grunts found themselves getting paid scale to play. It was everything, right down to an endless run of commercial jingles from national advertisers like Pepsi, Coke, Polaroid and Budweiser that started rolling off L.A.'s musical assembly line, as those companies seemingly overnight began re-imagining and rebranding their products to appeal to a younger, hipper audience, while at the same time casting aside their tired old stodgy jingles for ones that were youthful, contemporary and way more California-like in their sound and feel.

But it didn’t stop there. Television shows and movies too began using themes that sounded less like big bloated pieces of something out of your dad’s record collection, and more like the pop hits that kids were listening to and buying by the truckload in their local record stores. As a result, hundreds of TV and movie themes were no longer getting played by large in-house orchestras, or even small, artsy jazz combos. They were being recorded with the same assembly-line precision and by the same union hands who were laying down so much of the music that kids all over America were embracing as their own.

It was as though for ten or so years, any song played in America, regardless of where one heard it, and regardless of the context or situation under which it was heard, was recorded by a small but talented pool of musicians carrying a union card from Local 47 in their back pocket.

It was as though for ten or so years, any song played in America, regardless of where one heard it, and regardless of the context or situation under which it was heard, was recorded by a small but talented pool of musicians carrying a union card from Local 47 in their back pocket.

L.A. session players became so ubiquitous, in fact, that at one point two of them, Steve Barri and P.F. Sloan, sat down one day and wrote a couple of songs which, on a lark, they decided to lay down with a handful of fellow studio meat grinders. Liking what they heard, ABC offered Barri and Sloan a full-blown recording contract on the condition they lay down a few more originals, piece together an album, and tour to support it. The two dyed-in-the-wool session guys then, much to their chagrin, found themselves suddenly forced to go out, hire a real band, teach them how to play the songs they'd written, and send them on the road under the place-holder of a name they’d attached to themselves that day in the studio; the Grass Roots.

The other noteworthy aspect of the musicians of Local 47 during that golden age of pop was how well they were consistently able to mesh on any given day as a “band.” Sure there were always standout solo performances, depending on the arrangement, that could bring one instrument or player to the fore. But more often than not, those L.A. studio players had a unique way of marrying their individual talents, or even overlapping them, to create a sound that ended up being far greater than the sum of any one of its parts.

The other noteworthy aspect of the musicians of Local 47 during that golden age of pop was how well they were consistently able to mesh on any given day as a “band.” Sure there were always standout solo performances, depending on the arrangement, that could bring one instrument or player to the fore. But more often than not, those L.A. studio players had a unique way of marrying their individual talents, or even overlapping them, to create a sound that ended up being far greater than the sum of any one of its parts.

Therefore, while there were always standout solo performances during those halcyon days – Hal Blaine’s muscular, machine-gun drumming on Da Doo Ron Ron, Plas Johnson’s playful yet ultra-hip tenor sax lead in The Pink Panther Theme, Louis Shelton’s blistering flamenco-style guitar solo in the Monkees’ Valleri or the shimmering jingle-jangle of his 12-string throughout their Last Train to Clarksville, to name just a few – what really marked the era was the collective sounds those players were able to produce. And that was especially noteworthy given the fact that the listening devices being used by the kids were not sophisticated stereo systems, much less digital ones, but analog transistor (and/or car) radios tuned to the AM band and fitted with one or two mono speakers that could fit on the head of just about any coin in your pocket.

Therefore, while there were always standout solo performances during those halcyon days – Hal Blaine’s muscular, machine-gun drumming on Da Doo Ron Ron, Plas Johnson’s playful yet ultra-hip tenor sax lead in The Pink Panther Theme, Louis Shelton’s blistering flamenco-style guitar solo in the Monkees’ Valleri or the shimmering jingle-jangle of his 12-string throughout their Last Train to Clarksville, to name just a few – what really marked the era was the collective sounds those players were able to produce. And that was especially noteworthy given the fact that the listening devices being used by the kids were not sophisticated stereo systems, much less digital ones, but analog transistor (and/or car) radios tuned to the AM band and fitted with one or two mono speakers that could fit on the head of just about any coin in your pocket.

That’s why more than any one single performance or any one individual musician, critics and historians continue to cite the players' collective symphonic output or their collective impact -- such as Spector’s dense, cascading “Wall of Sound” or the layers of sounds, notes, instruments and noise-makers at play in such iconic recordings as Good Vibrations or Brian Wilson’s masterwork Pet Sounds -- as the true calling cards of that naïve but memorable era in American pop culture.

That’s why more than any one single performance or any one individual musician, critics and historians continue to cite the players' collective symphonic output or their collective impact -- such as Spector’s dense, cascading “Wall of Sound” or the layers of sounds, notes, instruments and noise-makers at play in such iconic recordings as Good Vibrations or Brian Wilson’s masterwork Pet Sounds -- as the true calling cards of that naïve but memorable era in American pop culture.

Musical Fingerprints

Musical Fingerprints

Artie Butler was one of those New Yorkers who had made the cross-country jaunt to the City of the Angels at some point in the mid-to-late ‘60s, and was a guy who left behind not only his hometown, but the place – and frankly the building – where he’d started to carve out a real name for himself. As a kid growing up in Brooklyn he taught himself to play instruments like the piano, drums and vibes and he used to dream about one day being a famous jazz or classical musician, even going so far as to paste his face in magazines like Downbeat and Metronome over those of greats like Buddy Rich, Benny Goodman, Errol Garner and Arthur Rubenstein.

But then one fateful day as a teenager he got hired as a keyboardist for a session in the old Brill Building by the legendary R&B team of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, and suddenly the world of pop, rock and R&B revealed itself to him as he'd never viewed it before. And soon Butler found himself starting to get work with producers in New York, in part because he was so multi-talented and so able to play just about any musical style imaginable, but in part because he was such a nice kid.

Soon Artie Butler’s fingerprints began popping up all over the musical landscape.

Soon Artie Butler’s fingerprints began popping up all over the musical landscape.

Consider; in 1963 producer Abner Spector, who doubled as an A&R man at Chess Records, hired him to arrange a tune written by his wife Lona Stevens and Zell Sanders and inspired by a children’s nursery rhyme. Artie admitted he wasn’t wild about the song as written, but felt it had potential. Give me a day or two, the polite young man told Spector, who assured Butler he would pay him for both his and his company’s time.

Butler and recording engineer Pat Jacques went into Jacques' small studio in the building that housed the Ed Sullivan Theater on Broaday with the sheet music and a pair of Ampex 350 mono tape machines -- one for recording and one for playback -- and began fiddling around with the song and a few different instruments. Before long he had arranged the tune, written for it an eerie, slightly haunting little piano part, which he played himself, and then laid down a few other instrumental parts, all of which he played himself, and all of which were recorded onto the same master reel.

Butler and recording engineer Pat Jacques went into Jacques' small studio in the building that housed the Ed Sullivan Theater on Broaday with the sheet music and a pair of Ampex 350 mono tape machines -- one for recording and one for playback -- and began fiddling around with the song and a few different instruments. Before long he had arranged the tune, written for it an eerie, slightly haunting little piano part, which he played himself, and then laid down a few other instrumental parts, all of which he played himself, and all of which were recorded onto the same master reel.

With each take, and with each instrumental part he laid down, Artie added a slightly different EQ and a slightly different variation of an echoing technique known as reverb. And all those rich, slightly echoed reverb effects, coupled with the “muddiness” the master tape naturally accrued after each take, gave the recording an eerie, hollow-sounding quality that worked perfectly with the composition’s minor key, as well as the bluesy piano riff that Butler had written to serve as the core of its arrangement.

All told, Butler ended up laying down the piano, Hammond B3 organ, drums, tambourine and upright bass parts that first day. And since he had no idea how to play the bass, he had to go to Jacques' secretary, borrow her lipstick, and mark the fingerboard of the instrument so he'd know where to place his hands and fingers.

A day or so later he then brought in Al Gorgoni to lay down some guitar parts and, finally, three girls from the Bronx who called themselves the Jaynetts to sing the rather cryptic but evocative lyrics. Not quite satisfied with the quality of the Jaynetts' singing, Butler decided to bring in a few more girls, then a few others after that – each time layering vocals upon vocals, and all the while tweaking each recording with the EQ and reverb dials.

A day or so later he then brought in Al Gorgoni to lay down some guitar parts and, finally, three girls from the Bronx who called themselves the Jaynetts to sing the rather cryptic but evocative lyrics. Not quite satisfied with the quality of the Jaynetts' singing, Butler decided to bring in a few more girls, then a few others after that – each time layering vocals upon vocals, and all the while tweaking each recording with the EQ and reverb dials.

By the time all was said and done, Butler reportedly had run up a bill of some magnitude. Though he told me recently he has no idea where the figure came from, Wikipedia claims that the work by the young arranger ran to some $60,000 and a week's worth of studio time, two figures that were almost unheard of at the time for the A side of a single. What’s more, Butler told me that Spector absolutely detested the finished product when he finally heard it – vehemently refusing to pay even a dime for the master tape.

So young Artie quietly left Spector and the studio, walked the recording down Broadway to the Brill Building office of his mentors, Leiber and Stoller, and played the tape for them. The two R&B legends loved it and told Butler they would buy it from Spector on the spot, no questions asked, and would reimburse the man for whatever he had invested in it. Only then did Spector reconsider and agree to pay Butler's company for the master, and only then did he decide to press the offbeat and heavily echoed recording and release it as a single.

So young Artie quietly left Spector and the studio, walked the recording down Broadway to the Brill Building office of his mentors, Leiber and Stoller, and played the tape for them. The two R&B legends loved it and told Butler they would buy it from Spector on the spot, no questions asked, and would reimburse the man for whatever he had invested in it. Only then did Spector reconsider and agree to pay Butler's company for the master, and only then did he decide to press the offbeat and heavily echoed recording and release it as a single.

Which is ironic, because today not only is Abner Spector listed as the sole producer of the classic, universally revered, and wildly influential Sally Go Round The Roses – which the Jaynetts rode all the way to #2 in 1963 – but in addition, through some publishing and copyrighting sleight-of-hand that he managed to pull off over the years, he’s now officially listed as the  sole composer of the song as well.

sole composer of the song as well.

And this from a guy who was nowhere to be found when the song was either written, arranged or recorded.

Butler, meanwhile, while not seeing a dime from the churlish producer, even union scale -- and who developed such a bitter taste in his mouth from the experience that he vowed never again to work with either Spector or the Jaynetts -- nevertheless got his very first on-label credit with Sally Go Round the Roses, and the song’s unmistakable cache among insiders up and down Broadway and throughout Tin Pan Alley began opening doors that just weeks prior had been closed to him.

A Defining Sound

A short time later, Butler went to work arranging for the famed Brill Building producing and songwriting team, Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich. And during that time it was Butler who helped define the sound of their greatest discovery; a young young singer/songwriter from Brooklyn named Neil Diamond, who recorded under the trio’s watchful eye for Bert Berns’ small but influential label, Bang Records.

And though Diamond would eventually relocate to L.A., would eventually stop working with Barry, Greenwich and Butler, and would eventually turn himself into something of a musical punchline, becoming a sequins-sporting, self-aware parody of a crooning balladeer – sort of his generation’s Robert Goulet – while he was in New York and recording for Bang, he was just about as good and as honest as a singer/songwriter could be. And a big part of Diamond’s early greatness was due to the fact that Butler had helped define him as a principled, truth-seeking musical loner through a series of stark and unvarnished arrangements of what were then Diamond’s remarkably unpretentious compositions.

And though Diamond would eventually relocate to L.A., would eventually stop working with Barry, Greenwich and Butler, and would eventually turn himself into something of a musical punchline, becoming a sequins-sporting, self-aware parody of a crooning balladeer – sort of his generation’s Robert Goulet – while he was in New York and recording for Bang, he was just about as good and as honest as a singer/songwriter could be. And a big part of Diamond’s early greatness was due to the fact that Butler had helped define him as a principled, truth-seeking musical loner through a series of stark and unvarnished arrangements of what were then Diamond’s remarkably unpretentious compositions.

Listen to Butler’s stripped-down, Spartan, yet soulful and sometimes stirring arrangements of such early Neil Diamond chestnuts as Cherry, Cherry, Kentucky Woman, The Boat that I Row, I Got the Feeling (No, No, No), Thank the Lord for the Nighttime and, especially, You Got to Me.

But above all, listen to Artie Butler’s note-perfect arrangement of what is, perhaps, one of the greatest and certainly most underrated recordings in the history of rock and roll, Diamond’s stunning version of his very first hit, Solitary Man – a record which, shockingly, climbed to no higher than #55 on the pop charts when it was released in 1966.

But above all, listen to Artie Butler’s note-perfect arrangement of what is, perhaps, one of the greatest and certainly most underrated recordings in the history of rock and roll, Diamond’s stunning version of his very first hit, Solitary Man – a record which, shockingly, climbed to no higher than #55 on the pop charts when it was released in 1966.

In the verses, Butler takes a less-is-more approach, letting a simple, crystal-clear acoustic lead guitar, a few rhythm guitars, a bass, and some drums carry the bulk of the load, while the young singer opens his heart and tells his tale of his gnawing tendency to love a woman and then lose her. In the chorus, however, out of the blue he adds a few low, understated trombones to the rhythm section, which lend a raw, almost palpable emotional backdrop to the singer’s lament. Yet even as he does this, he elevates the moment by introducing short stabs of horns, which not only allow the song to rise above simple melancholy but let it somehow serve as aural proof-positive of the young man’s resolve and his deep well of inner strength.

Rarely have an arrangement and a composition ever worked together so poignantly or more effectively on a single record, nor rarely has a single recording ever more clearly branded or defined a new singer.

Rarely have an arrangement and a composition ever worked together so poignantly or more effectively on a single record, nor rarely has a single recording ever more clearly branded or defined a new singer.

Another time, right around the same time as a matter of fact, Butler got called in by the legendary New York producer and soundman, George “Shadow” Morton. Morton,  whose protégés, the Shangri-Las, had almost single-handedly elevated teen angst and high school melodrama to mind-blowing proportions, wanted Butler to play keyboards on another brutally honest, socially polarizing song he had chosen to record, this one about a doomed interracial romance written by a 15 year old kid from New Jersey named Janis Ian. And on Society’s Child it is Artie Butler playing both the eerie harpsichord that Morton opens the (at the time) controversial song’s first verse and the brazen, clipped Hammond B3 organ he uses to end it in such a deliciously melodramatic manner.

whose protégés, the Shangri-Las, had almost single-handedly elevated teen angst and high school melodrama to mind-blowing proportions, wanted Butler to play keyboards on another brutally honest, socially polarizing song he had chosen to record, this one about a doomed interracial romance written by a 15 year old kid from New Jersey named Janis Ian. And on Society’s Child it is Artie Butler playing both the eerie harpsichord that Morton opens the (at the time) controversial song’s first verse and the brazen, clipped Hammond B3 organ he uses to end it in such a deliciously melodramatic manner.

What’s more, since he intended to lay down both sets of keyboards on the very same track and in the very same take, for the recording session that day Morton issued Butler a stool with four well-oiled wheels and told him to slide back and forth quietly between the harpsichord and the organ throughout each three-or-so minute take and play the two simultaneously.

What’s more, since he intended to lay down both sets of keyboards on the very same track and in the very same take, for the recording session that day Morton issued Butler a stool with four well-oiled wheels and told him to slide back and forth quietly between the harpsichord and the organ throughout each three-or-so minute take and play the two simultaneously.

Call of the Angels

Which brings us to the song of the day.

By 1968, Butler, like so many other New Yorkers in the music biz, had moved west to the City of the Angels. After all, that’s where the work was. And in the year or so hence, just as had been the case in New York, he had emerged as one of the most sought after pop arrangers in L.A.

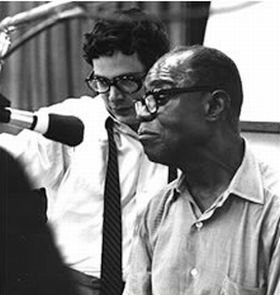

In fact, in that first year Butler had already arranged a handful of hits, including one special one that didn’t become a hit until a full two decades later. Called in late in the game, after the song's composer and its producer found themselves frustrated in their attempts to get things right, Artie ended up arranging and managing the session that would become Louis Armstrong’s swan song and his last great piece of studio work. The song was a stunningly beautiful ballad, one wrought with irony, given the riots, assassinations and war of the time, and one which -- perhaps because of all that irony and all those deep and festering emotional wounds – would not be embraced by listeners in the U.S. until 1988, when it was included in the soundtrack of the Barry Levinson movie, Good Morning, Vietnam. It was called What a Wonderful World.

In fact, in that first year Butler had already arranged a handful of hits, including one special one that didn’t become a hit until a full two decades later. Called in late in the game, after the song's composer and its producer found themselves frustrated in their attempts to get things right, Artie ended up arranging and managing the session that would become Louis Armstrong’s swan song and his last great piece of studio work. The song was a stunningly beautiful ballad, one wrought with irony, given the riots, assassinations and war of the time, and one which -- perhaps because of all that irony and all those deep and festering emotional wounds – would not be embraced by listeners in the U.S. until 1988, when it was included in the soundtrack of the Barry Levinson movie, Good Morning, Vietnam. It was called What a Wonderful World.

Then, one day in the spring of ’68, Butler got a call from British producer Denny Cordell for some arranging work he wanted done on behalf of a new artist he had taken under his wing. Cordell, an independent producer who had cut his teeth at Chris Blackwell’s Island Records for a few years, had achieved some measure of fame just a year or so prior for having been behind the glass during the session that produced Procol Harum’s baroque-pop anthem, A Whiter Shade of Pale.

Then, one day in the spring of ’68, Butler got a call from British producer Denny Cordell for some arranging work he wanted done on behalf of a new artist he had taken under his wing. Cordell, an independent producer who had cut his teeth at Chris Blackwell’s Island Records for a few years, had achieved some measure of fame just a year or so prior for having been behind the glass during the session that produced Procol Harum’s baroque-pop anthem, A Whiter Shade of Pale.

But he'd since become manager of a rising young British R&B singer named Joe Cocker, who was quickly making a name for himself by covering a number of contemporary pop and rock hits and putting his own rough-hewn spin on them – a spin which could at various times be raw, expressive, jazzy, raspy,  quirky, volcanic, daring, reverent and irreverent, all at the same time. In a few short years, Cocker proved be a force of nature in front of a mic – in a studio or on stage – gyrating, convulsing and giving himself over to a series of jaw-dropping tics, spasms and body and/or facial contortions, yet all the while singing with a combination of soulfulness, honesty and sheer vocal power evident in only a handful of contemporary artists at the time; people like Aretha Franklin, Levi Stubbs, Barbara Streisand, Van Morrison and Wilson Pickett.

quirky, volcanic, daring, reverent and irreverent, all at the same time. In a few short years, Cocker proved be a force of nature in front of a mic – in a studio or on stage – gyrating, convulsing and giving himself over to a series of jaw-dropping tics, spasms and body and/or facial contortions, yet all the while singing with a combination of soulfulness, honesty and sheer vocal power evident in only a handful of contemporary artists at the time; people like Aretha Franklin, Levi Stubbs, Barbara Streisand, Van Morrison and Wilson Pickett.

Cordell wanted Butler to arrange a little-known song by a breaking new English group called Traffic, written by guitarist Dave Mason and appearing on the band’s eponymous first album, which had been released just a few months prior. It was called Feelin’ Alright.

Butler had never  heard it before, but he looked at the music sheet when he met with Cordell and Cocker in the offices of A&M Records and immediately began hearing in his head a sort of driving Latin beat and a rollicking, full-bodied piano, all built around a funky little F chord. He walked around for nearly two days with that beat and that piano in his head, before finally going home and committing to paper a general structure for each musician Cordell had hired for the session. In fact, while at the piano that night at his home he made a conscious decision not to provide any of the musicians a note-by-note chart of what to play. Instead, he jotted down a general outline of the song's chord progression and when each player should play -- and perhaps just as important, not play.

heard it before, but he looked at the music sheet when he met with Cordell and Cocker in the offices of A&M Records and immediately began hearing in his head a sort of driving Latin beat and a rollicking, full-bodied piano, all built around a funky little F chord. He walked around for nearly two days with that beat and that piano in his head, before finally going home and committing to paper a general structure for each musician Cordell had hired for the session. In fact, while at the piano that night at his home he made a conscious decision not to provide any of the musicians a note-by-note chart of what to play. Instead, he jotted down a general outline of the song's chord progression and when each player should play -- and perhaps just as important, not play.

The beauty of the session in Butler’s mind was that it was only going to include four players – in essence, a four-man band – and rather than consigning each to a hard-and-fast and specific set of notes or beats, he put together a general chord structure from which each could improvise and play what he or she felt. What he created, in other words, was a jazz arrangement for a jazz quartet.

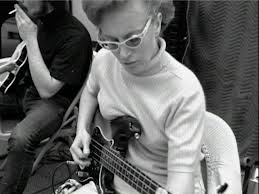

That was in part because the rhythm section Cordell had hired for the session, bassist Carol Kaye and drummer Paul Humphries, were not only in their hearts jazz musicians, they were stunningly talented players. Like so many members of Local 47, they played pop, rock and such for a paycheck, but when the occasion arose, they played jazz because they loved it.

That was in part because the rhythm section Cordell had hired for the session, bassist Carol Kaye and drummer Paul Humphries, were not only in their hearts jazz musicians, they were stunningly talented players. Like so many members of Local 47, they played pop, rock and such for a paycheck, but when the occasion arose, they played jazz because they loved it.

Kaye had grown up idolizing Charlie Christian, who found modest fame as one of the pioneers of jazz guitar while playing with Benny Goodman, and she brought not only an amazing sense of  rhythm and backbeat to the bass, but Christian’s melodic sense of playfulness and improvisation as well. As a result, she quickly became, arguably, the single most in-demand bassist on the America pop scene and her playing – both on guitar and bass – could soon be heard on everything from Pet Sounds and Good Vibrations to You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feeling by the Righteous Brothers, River Deep, Mountain High by Ike and Tina Turner, and Wichita Lineman by Glen Campbell.

rhythm and backbeat to the bass, but Christian’s melodic sense of playfulness and improvisation as well. As a result, she quickly became, arguably, the single most in-demand bassist on the America pop scene and her playing – both on guitar and bass – could soon be heard on everything from Pet Sounds and Good Vibrations to You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feeling by the Righteous Brothers, River Deep, Mountain High by Ike and Tina Turner, and Wichita Lineman by Glen Campbell.

Kaye’s distinctive bass work could also be heard on classic television themes like those from Mission: Impossible, M*A*S*H and The Wild, Wild, West, to name just a few, and on such timeless movie themes as The Way We Were.

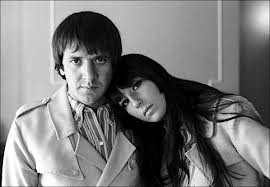

But her importance as a sideman was perhaps never more in evidence – at least to the layman – than it was in 1967 while playing guitar during a session for Sonny and Cher, in which the former was also serving as producer. Some of the regulars from Local 47 were working that day on a song Bono had just penned titled The Beat Goes On. Kaye would later call Bono’s bland and rather colorless little ditty – which he had written using only one chord – a “dog,” and found herself utterly bored to tears trying to slog through it.

But her importance as a sideman was perhaps never more in evidence – at least to the layman – than it was in 1967 while playing guitar during a session for Sonny and Cher, in which the former was also serving as producer. Some of the regulars from Local 47 were working that day on a song Bono had just penned titled The Beat Goes On. Kaye would later call Bono’s bland and rather colorless little ditty – which he had written using only one chord – a “dog,” and found herself utterly bored to tears trying to slog through it.

And she was not alone. Each take grew less and less inspired as the union musicians began to realize that, with the song written and arranged as is, they had absolutely nothing to work with. At one point about two hours into the increasingly expensive session, the noted studio guitarist Barney Kessel, himself a member of good standing in the Wrecking Crew and, likewise, a dyed-in-the-wool be-bop fanatic, said in frustration, “Never have so many played so little for so much.”

Finally, Kaye during one take just began strumming on her guitar something that, for all the world, sounded like one of her signature bass lines. But she was playing it on her guitar. Just a simple, nine-note musical phrase – dum dum dum dum dum dum-dum dum dum – that she kept repeating over and over. Immediately Bono shot out of the booth, looked in her direction and asked, “Carol, what was that you were just playing?” She played it again for him again, and he quickly turned to the bass player and said something like, “That’s it! That’s it! Just play that, OK?”

Finally, Kaye during one take just began strumming on her guitar something that, for all the world, sounded like one of her signature bass lines. But she was playing it on her guitar. Just a simple, nine-note musical phrase – dum dum dum dum dum dum-dum dum dum – that she kept repeating over and over. Immediately Bono shot out of the booth, looked in her direction and asked, “Carol, what was that you were just playing?” She played it again for him again, and he quickly turned to the bass player and said something like, “That’s it! That’s it! Just play that, OK?”

That was indeed it. And once it happened, the session wrapped a few takes later. And years later, that simple yet distinctive nine-note run – one dreamed up on the spot by Carol Kaye and repeated by the bassist throughout the duration of The Beat Goes On -- not only defines the song, it is probably the only reason anyone beyond Sonny, Cher, a recording engineer and a handful of union grunts from Local 47 even knows it exists.

That was indeed it. And once it happened, the session wrapped a few takes later. And years later, that simple yet distinctive nine-note run – one dreamed up on the spot by Carol Kaye and repeated by the bassist throughout the duration of The Beat Goes On -- not only defines the song, it is probably the only reason anyone beyond Sonny, Cher, a recording engineer and a handful of union grunts from Local 47 even knows it exists.

Meanwhile, the drummer Cordell booked for Feelin’ Alright, Humphries, was likewise was a jazz and be-bop cat. And while he played on such pop  and soul hits as Marvin Gaye’s Let’s Get it On and others, he was much more in his element playing jazz, and often doing so live and on stage or in a local club. That’s why when jazz titans like Wes Montgomery, Charles Mingus, Kai Winding and Jimmy Smith wanted a talented drummer who could play hot and cool with equal grace and bravado, and play both in front of an audience and in the studio, quite often the guy they called was Paul Humphries.

and soul hits as Marvin Gaye’s Let’s Get it On and others, he was much more in his element playing jazz, and often doing so live and on stage or in a local club. That’s why when jazz titans like Wes Montgomery, Charles Mingus, Kai Winding and Jimmy Smith wanted a talented drummer who could play hot and cool with equal grace and bravado, and play both in front of an audience and in the studio, quite often the guy they called was Paul Humphries.

Laying It Down

The day they went into lay down Feelin’ Alright, the “band” as assembled by Cordell included just five people, Butler, Kaye, Humphries, guitarist David Cohen, and of course, Cocker. Based on what Butler’s arrangement called for, he would bring in percussionist Laudir de Oliveira to lay down both a conga and a jawbone track, and singers Merry Clayton and Brenda and Patrice Holloway to provide background vocals a few days later. But to lay down the foundation of the recording – again, per Butler’s Latin-sounding and jazz-inspired “arrangement” – it would just be those five, with only the first four together in the main studio.

As he drove to A&M that morning, Butler sensed he was onto something. And that became even more apparent an hour or so later as the four members of Local 47 started to run through the song in rehearsal. The studio was rippling with energy and life. Things crackled. They clicked. Everyone felt it. And Kaye and Humphries, finding themselves untethered by the rigid structure of a traditional (and sometimes) tepid pop arrangement, and given the kind of freedom one might bestow upon a great jazz artist, grew more energetic and more expressive with each passing rehearsal.

As he drove to A&M that morning, Butler sensed he was onto something. And that became even more apparent an hour or so later as the four members of Local 47 started to run through the song in rehearsal. The studio was rippling with energy and life. Things crackled. They clicked. Everyone felt it. And Kaye and Humphries, finding themselves untethered by the rigid structure of a traditional (and sometimes) tepid pop arrangement, and given the kind of freedom one might bestow upon a great jazz artist, grew more energetic and more expressive with each passing rehearsal.

As Butler would tell me on the phone years later, “That day the magic was in the air, no doubt. It was so powerful and strong. Just four artists in a groove. And as musicians, it was everything we played music for in the first place, in all its power and all its passion.”

And that’s what you hear when you hear Joe Cocker’s version of Feelin’ Alright today; both power and that passion. Those things were evident then, but they’re perhaps even more evident now, because the stature of the song, not to mention its influence, has grown tremendously with the passage of time. I’ve communicated with Carol Kaye a couple of times over the years, and each time she’s brought up the Feelin’ Alright session, and the great work done by both Butler and Humphries – the latter of whom after one particularly smoking take was so caught up in the groove that he laughed and blurted out, “Carol, marry me!”

After all this time and after all these years, Kaye is still very proud of her work on Feelin' Alright, as well she should be. Because beyond Butler’s raucous piano which carries much of the load melodically, it is Kaye’s largely improvised bass part that helps give the song its sense of fury, its kinetic, driving rhythm and, ultimately, its ability to reach a higher gear.

After all this time and after all these years, Kaye is still very proud of her work on Feelin' Alright, as well she should be. Because beyond Butler’s raucous piano which carries much of the load melodically, it is Kaye’s largely improvised bass part that helps give the song its sense of fury, its kinetic, driving rhythm and, ultimately, its ability to reach a higher gear.

But back to Butler. It must have taken some bold combination of musical chops and professional hutzpah to arrange Feelin’ Alright as he did, because if you listen to it closely he plays the entire first verse all by himself; just him and his piano. No one else there that day was invited to join him until the chorus.

But that’s the true genius of his arrangement. Because listen to the song closely; as Cocker, Butler and his piano continue to tear apart the song’s first verse, you can almost sense Kaye and Humphries to the side, chomping at the bit, dying to join in the groove that Butler is creating, a groove that boldly and brazenly continues to arc skyward. And then, just as the cork pops and the chorus kicks in, Kaye and Humphries dive in head-first.

But that’s the true genius of his arrangement. Because listen to the song closely; as Cocker, Butler and his piano continue to tear apart the song’s first verse, you can almost sense Kaye and Humphries to the side, chomping at the bit, dying to join in the groove that Butler is creating, a groove that boldly and brazenly continues to arc skyward. And then, just as the cork pops and the chorus kicks in, Kaye and Humphries dive in head-first.

And when they start playing, and when the two hit the ground running in what amounts to a full-blown, knock-down, drag-out funkfest, it’s as though some trainer, who’d been holding back two powerful strutting, snorting thoroughbreds, suddenly opens his fingers and releases them, freeing each to do the one thing God has seemingly put them on this earth to do.

At it is in the chorus where Joe Cocker’s version of Feelin’ Alright does indeed find that higher gear and becomes something more than just one more cover of one more rock and roll standard.

At it is in the chorus where Joe Cocker’s version of Feelin’ Alright does indeed find that higher gear and becomes something more than just one more cover of one more rock and roll standard.

Because in the opinion of many, that’s what the song sounds like in Traffic’s hands; a very nice rock and roll song, but something this side of legendary. As sung by Mason, and played by people like Steve Winwood and Jim Capaldi, Traffic’s arrangement of Feelin’ Alright feels like a perfectly fine moment in British folk-rock history. But that’s it. It is a terrific recording, and it is more than merely listenable, but it hardly grabs you by your lapels and bitch slaps you across the face -- which is exactly what Cocker's version does.

That’s why when you hear the song covered these days – and, make no mistake; it still continues to get covered by generations of new and wildly different artists – what you’re likely to hear is not so much a cover, but a cover of a cover. There's a real good chance that what you're listening to is yet one more new and updated version of not so much Feelin’ Alright as written, but Artie Butler’s arrangement of it.

That’s why when you hear the song covered these days – and, make no mistake; it still continues to get covered by generations of new and wildly different artists – what you’re likely to hear is not so much a cover, but a cover of a cover. There's a real good chance that what you're listening to is yet one more new and updated version of not so much Feelin’ Alright as written, but Artie Butler’s arrangement of it.

Butler told me that despite all the years that have passed since the song was released he still gets people regularly reaching out to him because of Feelin’ Alright, and to this day still receives as many as a dozen or so unsolicited emails a week from fans near and far asking about, commenting on, or thanking him for his contributions to the recording -- and in particular, that F chord.

In our conversation a year or so ago, when I asked him about his remembrances of the session and about the making of Cocker’s version of the tune, he gently minimized his role in the song's lasting legacy and instead gave credit where he still believes credit is due. He said simply, “The smartest thing I did that day? I didn’t tell (the musicians) what to play. I told them when to play.”

In our conversation a year or so ago, when I asked him about his remembrances of the session and about the making of Cocker’s version of the tune, he gently minimized his role in the song's lasting legacy and instead gave credit where he still believes credit is due. He said simply, “The smartest thing I did that day? I didn’t tell (the musicians) what to play. I told them when to play.”

So with that, please enjoy M.C. Antil’s Song of the Day for Friday, November 30, 2012, Artie Butler’s blistering, raucous and extra-spicy arrangement (and performance) of what has over the years become one of the staples of the rock and roll lexicon, Joe Cocker’s joyous cover of Dave Mason’s Feelin’ Alright – a song now in its sixth decade and a song he recorded with more than a little help from his friends.

Song: Feelin' Alright

Artist: Joe Cocker

Composer: Dave Mason

Year Released: 1968