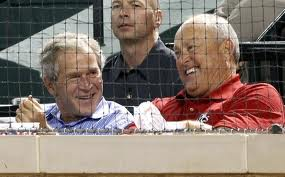

I’ve always found it deliciously ironic that Texas Ranger head honcho and franchise icon Nolan Ryan often sits during games with his fellow Texan and political soul-mate, George W. Bush. Because it was Bush who inspired the late Texas governor and noted Lone Star hip-shooter Ann Richards to quip famously about the one-time frat boy-turned-chief executive, “He was born on third base and thought he hit a triple.”

I’ve always found it deliciously ironic that Texas Ranger head honcho and franchise icon Nolan Ryan often sits during games with his fellow Texan and political soul-mate, George W. Bush. Because it was Bush who inspired the late Texas governor and noted Lone Star hip-shooter Ann Richards to quip famously about the one-time frat boy-turned-chief executive, “He was born on third base and thought he hit a triple.”

The irony, of course, is that Ryan – who in just two short years has emerged as baseball's answer to Mr. Born on Third himself – has very subtly allowed himself to be given (and accept) the lion’s share of the credit for the remarkable turnaround of the once-forlorn Rangers, and now regularly positions himself as the face of the club's success.

Nolan Ryan? Really? C'mon. Because I'm telling you right now, nothing could be further from the truth – no more, frankly, than the idea that a previous face of a franchise, Ted Turner, had somehow been responsible for the stunning turnaround of his once-hapless team.

Let’s get one thing straight, shall we? Long before Chuck Greenburg and his fellow investors ever approached Ryan about becoming the public face of their deep-pocketed group, and long before that group ever won the right to buy the Rangers from that loose cannon and Steinbrenner-on-training wheels, the then-bankrupt Tom Hicks, in August of 2010, GM Jon Daniels had already entirely rebuilt the Texas farm system and had already put the Rangers on a path that would eventually lead them to the World Series.

Let’s get one thing straight, shall we? Long before Chuck Greenburg and his fellow investors ever approached Ryan about becoming the public face of their deep-pocketed group, and long before that group ever won the right to buy the Rangers from that loose cannon and Steinbrenner-on-training wheels, the then-bankrupt Tom Hicks, in August of 2010, GM Jon Daniels had already entirely rebuilt the Texas farm system and had already put the Rangers on a path that would eventually lead them to the World Series.

Before the Hall of Famer and strikeout king even entered into the picture, Daniels had aleady swung a deal with the Braves and had already turned free agent-to-be Mark Teixeira into Elvis Andrus, Matt Harrison, Jarrod Saltalamacchia and Neftali Feliz.

He had already flipped fading closer Eric Gagne to Boston for two unknown prospects, one of whom, David Murphy, quickly made a name for himself by regularly doing little things to help win games.

He had already flipped fading closer Eric Gagne to Boston for two unknown prospects, one of whom, David Murphy, quickly made a name for himself by regularly doing little things to help win games.

He had already swapped out spare parts, Kevin Mench and Francisco Cordero, for a package from Milwaukee that included fading minor league slugger, Nelson Cruz, who almost immediately started to figure things out in Arlington.

Jon Daniels had already traded the live-armed but erratic Edison Volquez to Cincinnati for the far more talented but infinitely riskier Josh Hamilton, who then emerged as an All Star fixture, copped an MVP award, and hit four HR in a game in which he also threw in a 2B to boot.

Jon Daniels had already traded the live-armed but erratic Edison Volquez to Cincinnati for the far more talented but infinitely riskier Josh Hamilton, who then emerged as an All Star fixture, copped an MVP award, and hit four HR in a game in which he also threw in a 2B to boot.

And before Nolan Ryan ever came on board, Daniels had already drafted and/or signed useful pieces and marketable parts, Chris Davis, Justin Smoak, Blake Beavan, Alexi Ogando, Scott Feldman, Julio Borbon and Mitch Moreland, to name just a few.

In fact, in Daniels’ first full season as GM, Baseball America vaulted the Rangers from 17th place all the way to 4th in their annual organizational rankings, the biggest one-year leap any MLB organization had ever taken since the publication came into being.

In fact, in Daniels’ first full season as GM, Baseball America vaulted the Rangers from 17th place all the way to 4th in their annual organizational rankings, the biggest one-year leap any MLB organization had ever taken since the publication came into being.

Make no mistake; Jon Daniels did those things. Jon Daniels drafted and signed all that talent. Jon Daniels traded for those future stars. And for that reason, Jon Daniels is the one who deserves the praise.

He’s the one who emerged as the man behind the Rangers' Texas-sized makeover. And he’s the one who transformed them.

He’s the one who emerged as the man behind the Rangers' Texas-sized makeover. And he’s the one who transformed them.

Not Nolan Ryan.

And this is where the gods of baseball come in. Because Ryan did more than just take oh-so-subtle credit for much of what Daniels did by hogging the spotlight at every possible turn. He helped screw up much what the Rangers had going for them by squandering virtually every last drop of good baseball karma they had accumulated.

First, apparently sick and tired of Greenburg’s “man of the people” act – in which the gregarious but occasionally grating New Jersey-born and raised millionaire owner and general partner, dressed in jeans and a tee shirt, would often walk and sit among the fans, drink beer with them, ask how he might improve their game experience, and (much like Mark Cuban across town) sit and shamelessly and whole-heartedly root for the team he owned – Ryan played Brutus to Greenburg’s Caesar, staged a palace coup, and behind closed doors used his name and clout to squeeze his partner out after only a few months.

Next he took, arguably, the best broadcast team in baseball and simply tore it apart. Josh Lewin – who, like Greenburg, was an outgoing, geeky-smart, baseball-loving Jewish kid from the Northeast – had teamed with genial Ranger company man and uncle figure Tom Grieve for nine seasons, and had become one half of a Mutt-and-Jeff act that, for my money, was responsible for the most enjoyable and entertaining baseball telecasts in the game. As a result, long before Texas ever became a full-fledged contender and post-season fixture, I found myself regularly tuning in to Rangers games, and not just because they featured eye-popping young talent, but because I so enjoyed Lewin and Grieve’s easy going blend of game-calling, analysis, repartee and pop culture ping pong.

Next he took, arguably, the best broadcast team in baseball and simply tore it apart. Josh Lewin – who, like Greenburg, was an outgoing, geeky-smart, baseball-loving Jewish kid from the Northeast – had teamed with genial Ranger company man and uncle figure Tom Grieve for nine seasons, and had become one half of a Mutt-and-Jeff act that, for my money, was responsible for the most enjoyable and entertaining baseball telecasts in the game. As a result, long before Texas ever became a full-fledged contender and post-season fixture, I found myself regularly tuning in to Rangers games, and not just because they featured eye-popping young talent, but because I so enjoyed Lewin and Grieve’s easy going blend of game-calling, analysis, repartee and pop culture ping pong.

This is not the time or the place to detail how just well the two used to play off one another. But suffice it to say that Lewin – who not only played in a Dallas-area rock band and often read books and quoted sources about things far afield from baseball, but who displayed an encyclopedic knowledge of history and dipped into a broad and often esoteric stash of pop culture touchstones – was not really Ryan’s type of guy. He was probably a little too, I don’t know, different for the big Texan's tastes.

As a result, Lewin’s contract was not renewed by Ryan after the 2010 season. Meanwhile, at the same time the Rangers' CEO gave his blessing to a new play-by-play man who proved to be so remarkably inept that club officials mercifully pulled the plug and relegated him to pre-game duty only weeks into the 2011 season.

As a result, Lewin’s contract was not renewed by Ryan after the 2010 season. Meanwhile, at the same time the Rangers' CEO gave his blessing to a new play-by-play man who proved to be so remarkably inept that club officials mercifully pulled the plug and relegated him to pre-game duty only weeks into the 2011 season.

But that’s not all Ryan did, nor were those the only ways he tweaked the noses of the baseball gods. He eventually did something far worse and, at least in their eyes, far more unpardonable.

Early in 2011, after having dictated that Daniels sign free agent Adrian Beltre to replace long-time Texas base hit machine and All Star Michael Young at 3B, Ryan went on what seemed to be a one-man crusade to justify his free agent signing by denigrating Young at every possible turn.

Early in 2011, after having dictated that Daniels sign free agent Adrian Beltre to replace long-time Texas base hit machine and All Star Michael Young at 3B, Ryan went on what seemed to be a one-man crusade to justify his free agent signing by denigrating Young at every possible turn.

Ryan was, in fact, so openly disdainful of Young’s fielding and run producing abilities that at times his comments seemed to defy reason. From the outside looking in, it appeared that Ryan was trying to defend his decision to sign Beltre, not so much by singing the praises of the new guy, but by systematically running down the old one -- a player, mind you, still wearing a Ranger uniform.

Truth be told, I found what Ryan did unconscionable, regardless of the circumstance, but especially because he was doing it to such a fiercely loyal teammate and such a remarkably classy individual as Michael Young.

Ryan seemed to conveniently forget that Young, a SS by trade, had moved to 2B in '01 when Hicks' unexpectedly signed free agent SS Alex Rodriguez. He then became an All Star at his new position many times over.

Ryan seemed to conveniently forget that Young, a SS by trade, had moved to 2B in '01 when Hicks' unexpectedly signed free agent SS Alex Rodriguez. He then became an All Star at his new position many times over.

Then when the Rangers brought in young Alfonso Soriano to play 2B a few years later, Young selflessly shifted back to SS to accommodate him. And once again he became an All Star, and won a Gold Glove to boot.

A few years after that, the Rangers brought up young phenom Elvis Andrus and promptly gave him Young’s starting job, so the deposed SS (begrudgingly, but nevertheless quietly and with the dignity and class he’d always shown) shifted over to 3B, where once again he worked hard and once again turned himself into an All Star.

Ryan’s relentless anti-Young crusade before the 2011 season, in fact, became so extreme and so public that at one point during spring training the Rangers’ CEO actually orchestrated a trade of the selfless Young to Colorado for little more than a used dish rag, and did so without a whiff of hesitation or regret. Fortunately for Ryan, the Rockies nixed the deal when concerns over Young’s health arose.

Ryan’s relentless anti-Young crusade before the 2011 season, in fact, became so extreme and so public that at one point during spring training the Rangers’ CEO actually orchestrated a trade of the selfless Young to Colorado for little more than a used dish rag, and did so without a whiff of hesitation or regret. Fortunately for Ryan, the Rockies nixed the deal when concerns over Young’s health arose.

I say fortunately because all Young did that year was help Ryan and the Rangers return to the World Series by hitting .338 for the season, leading them in BA, hits, 2B, OBP and RBI, serving as the team’s primary DH, and filling in multiple times at all four infield positions.

As a result, the Rangers' former odd-man-out finished the year 8th in the MVP balloting.

All of this, of course, is a roundabout way of saying there are many ways to cross the baseball gods, and many different ways to ensure that baseball heartbreak will soon become a regular part of your life for far longer than you ever imagined possible.

Ask the Red Sox and former owner Harry Frazee, who once sold Boston’s best player, the immortal Babe Ruth, to the Yankees for enough money to finance one of his Broadway productions. And ask the loyal fans of the Sox what it felt like to then spend nearly a century as victims of the vengeful and often cruel baseball gods, and to witness first hand their unrelenting wrath.

Ask the Red Sox and former owner Harry Frazee, who once sold Boston’s best player, the immortal Babe Ruth, to the Yankees for enough money to finance one of his Broadway productions. And ask the loyal fans of the Sox what it felt like to then spend nearly a century as victims of the vengeful and often cruel baseball gods, and to witness first hand their unrelenting wrath.

Ask the Cubs who once alienated one of their most loyal season ticket holders by forbidding him to bring his pet goat to the 1945 World Series, and who have been trying to make it up to the baseball gods ever since – unsuccessfully I might add.

Heck, ask the Red Sox again about the time in 2003 when for some reason they found it in themselves to paint the World Series logo on the OF grass at Fenway Park just before Pedro Martinez took the mound for Game Seven of the ALCS against Aaron Boone and the hated Yankees. And while you’re at it, ask how that little affront to the baseball gods’ sense of timing, decorum and procedure ended up working out for them.

Heck, ask the Red Sox again about the time in 2003 when for some reason they found it in themselves to paint the World Series logo on the OF grass at Fenway Park just before Pedro Martinez took the mound for Game Seven of the ALCS against Aaron Boone and the hated Yankees. And while you’re at it, ask how that little affront to the baseball gods’ sense of timing, decorum and procedure ended up working out for them.

And while clearly Nolan Ryan has not done anything nearly so conspicuous or nearly as fable-inspiring as either the Red Sox or the Cubs, don’t think for a minute he hasn’t tweaked the gods’ noses in a big way since taking over the Rangers.

After all, he continues to take subtle credit for his general manager's remarkable run of player personnel decisions.

He stabbed in the back the very guy who rescued his club from a bankrupt, clueless owner and ensured its solvency, and betrayed the very man who made his own ownership of the team possible.

He summarily dismissed one of the finest, most entertaining play-by-play men this side of Vin Scully for no apparent reason other than the fact that, perhaps, he just didn’t get him.

He summarily dismissed one of the finest, most entertaining play-by-play men this side of Vin Scully for no apparent reason other than the fact that, perhaps, he just didn’t get him.

But more than anything else, in his own self-interest he once attempted to destroy the reputation of one of the classiest, most respected and selfless gentlemen the game has ever produced, as well as one of its finest hitters.

Don’t for a minute think the gods of the game were going to let those sins go unpunished; especially the last one.

My sense is that all that bad baseball mojo was at least partly responsible for what happened two years ago when Ryan’s powerful and heavily favored Rangers fell meekly to the offensively challenged 2010 Giants in a five-game World Series.

My sense is that all that bad baseball mojo was at least partly responsible for what happened two years ago when Ryan’s powerful and heavily favored Rangers fell meekly to the offensively challenged 2010 Giants in a five-game World Series.

I get the feeling bad baseball karma was at least partly to blame for why in 2011, with the national media and their lenses fixed squarely on him (and not Daniels) for what all assumed would be the final strike of the Series – on two different occasions, no less – the Cardinals were able to claw back and shock Ryan and his once-again, heavily favored Rangers.

That’s why this past week, the Oakland A’s – a collection of players that baseball lifer Billy Beane seemed to piece together with a crescent wrench, a shoestring and a few miles of duct tape – were able to chase down and catch the ungodly deep and unholy rich Rangers on the final day of the season and in the process snatch away a division crown that, literally, just hours prior seemed a foregone conclusion.

That’s why this past week, the Oakland A’s – a collection of players that baseball lifer Billy Beane seemed to piece together with a crescent wrench, a shoestring and a few miles of duct tape – were able to chase down and catch the ungodly deep and unholy rich Rangers on the final day of the season and in the process snatch away a division crown that, literally, just hours prior seemed a foregone conclusion.

And that’s also why what was left of those still-reeling Rangers after that shocking meltdown proved to be little more than road kill as they got thoroughly trounced by the upstart Orioles in the AL Wild Card game.

I don’t recall seeing Nolan Ryan in his usual field-level box during the telecast of that humiliating loss to the O’s last week, nor frankly do I recall seeing him during any of those games against the A’s. Maybe he was there. But maybe he wasn’t.

Maybe the Rangers CEO finally came to understand that the baseball gods were simply not going to smile on him that or any other day, and that there wasn’t much of a point. It was all just an exercise in futility and the fix was already in.

Maybe Ryan realized -- just like the Red Sox and Cubs eventually did over the course of so many years, so many broken hearts, and so many empty, fruitless summers -- that what happens in baseball isn’t always a product of what transpires on the field. It’s sometimes a matter of what’s perpetrated off it.

And in some instances – such as, perhaps, the case of Nolan Ryan – it may just come down to what some higher-up in the front office has done to run afoul of the baseball gods; those disembodied spirits who look down from on high and preside over all that happens, foul pole to foul pole; those often fickle string-pullers who watch every last inning of every last game with the power to make that little white ball do the funniest things at the funniest possible time; and those mystical beings and lords of fate who, time and time again, have proven they have a remarkable ability to harbor the deepest grudge, possess the longest memory, and impart a brand of justice that is, truly, all their own.

And in some instances – such as, perhaps, the case of Nolan Ryan – it may just come down to what some higher-up in the front office has done to run afoul of the baseball gods; those disembodied spirits who look down from on high and preside over all that happens, foul pole to foul pole; those often fickle string-pullers who watch every last inning of every last game with the power to make that little white ball do the funniest things at the funniest possible time; and those mystical beings and lords of fate who, time and time again, have proven they have a remarkable ability to harbor the deepest grudge, possess the longest memory, and impart a brand of justice that is, truly, all their own.