A few working actors catch lightning in a bottle and get their names above the title, while earning the kind of perks that go along with that level of mega-fame. The balance would consider themselves fortunate if they found work for the rest of their lives and lived out their days earning a living at something they love.

A few working actors catch lightning in a bottle and get their names above the title, while earning the kind of perks that go along with that level of mega-fame. The balance would consider themselves fortunate if they found work for the rest of their lives and lived out their days earning a living at something they love.

In between, however, are those handful of actors lucky enough to wake up one day to realize they've acted in a landmark production or film, or that they've created an iconic character that somehow has worked its way into our collective consciousness. Think Burt Lahr in The Wizard of Oz, Don Knotts as Barney Fife or Lee J. Cobb’s Willy Loman.

I once told Jamie Hector, who played Marlo Stanfield, the ambitious and utterly ruthless badass on HBO’s The Wire – a show many critics feel might have been the greatest the history of the medium – that no matter where his career went, from this point forward he would always be playing with house money. Regardless of what happens to you as an actor, I told him, years from now you will always be able to tell your grandkids you were in The Wire.

I once told Jamie Hector, who played Marlo Stanfield, the ambitious and utterly ruthless badass on HBO’s The Wire – a show many critics feel might have been the greatest the history of the medium – that no matter where his career went, from this point forward he would always be playing with house money. Regardless of what happens to you as an actor, I told him, years from now you will always be able to tell your grandkids you were in The Wire.

It’s not a stretch to consider William Windom one such performer. Windom, a New York-born actor who died this week at the age of 88, worked over the course of his career in any number of cheesy, even awful sitcoms and dramas. In fact, there was a thirty year stretch between about 1960 and 1990 when it was probably hard to turn on a prime time TV show and not stumble upon Windom playing one rumpled, befuddled or slightly dog-eared character or another.

But he also was blessed to have performed in three utterly terrific screen productions, all three of which were artistically significant in their own right and one of which has slowly become one of the most universally beloved movies in history.

But he also was blessed to have performed in three utterly terrific screen productions, all three of which were artistically significant in their own right and one of which has slowly become one of the most universally beloved movies in history.

Two of them, however, were just about the opposite of beloved; two small screen productions that were largely dismissed by the mainstream public when they were released, and two which remain all but forgotten by most people -- expect, of course, those of us with the geek gene.

My World and Welcome to It

My World and Welcome to It

There was once a wonderful little half-hour sitcom called My World and Welcome to It. The series, which ran for the 1969-70 season on NBC, was drawn – no pun intended – on New Yorker cartoons created by the late humorist James Thurber. To say that the series was ahead of its time would be entirely inaccurate. The show was decades behind its time. Its time was the 1920s, and its creative inspiration was the likes of Thurber, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley and the rest of the often besotted knights of the Algonquin Roundtable.

And My World and Welcome to It was not only by, for and about the tweed-loving, Ivy-walled professional wits and wags who rode the train into Manhattan every day from manicured and well-appointed destinations in Connecticut, where the show was based, but it was way too smart for mainstream tastes. Trying to find an audience in a country in love with Gilligan’s Island by using characters loosely based on people like Parker and Benchley was nothing short of ratings suicide. But somehow the show not only got made, it was given a full 26-episode run by the network.

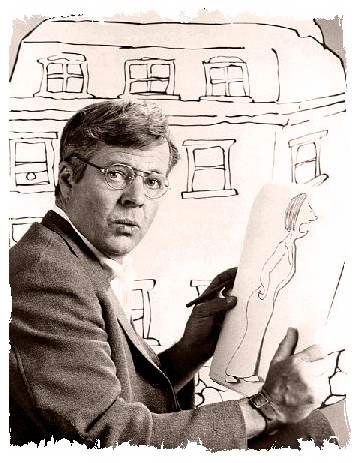

My World and Welcome to It was a wonderful artistic achievement, especially for weekly television. It mixed quality animation with live action footage, as Thurber-like cartoons would come to life in brief animated sequences created by the same people responsible for cartoon icons like the Pink Panther and Yosemite Sam. At the same time, the show’s live action sequences would seamlessly alternate back and forth between fantasy and reality.

At the center of it all was Windom, a talented, somewhat cynical and largely put-upon family man/writer and cartoonist named John Monroe who, much like Thurber’s Walter Mitty, finds an escape from the humdrum and pressures of everyday life by retreating into his own imagination. As Monroe, Windom brought heart, humanity and an understated, everyman quality to the role.

At the center of it all was Windom, a talented, somewhat cynical and largely put-upon family man/writer and cartoonist named John Monroe who, much like Thurber’s Walter Mitty, finds an escape from the humdrum and pressures of everyday life by retreating into his own imagination. As Monroe, Windom brought heart, humanity and an understated, everyman quality to the role.

But Windom’s performance, or even the show’s animation, was not what made My World and Welcome to It memorable. It was the subtle wit and the often dry humor it trafficked in; it was the (at the time) non-traditional sitcom terrain its writers loved to mine, like conformity, consumerism and America’s culture war; and it was, above all, the simple fact the show ever got green-lighted by the network in the first place.

With ratings consistently in the tank and most viewers clearly turning up their noses at a sitcom about people who worked for and (gulp) actually read a fictional magazine that looked an awful lot like the New Yorker, My World and Welcome to It found itself, not surprisingly, dropped from NBC’s primetime slate after just one season. But not before the show became a darling of critics, won the Emmy for Outstanding Comedy Series, and earned Windom the only Emmy of his career, as Lead Actor in a Comedy Series.

With ratings consistently in the tank and most viewers clearly turning up their noses at a sitcom about people who worked for and (gulp) actually read a fictional magazine that looked an awful lot like the New Yorker, My World and Welcome to It found itself, not surprisingly, dropped from NBC’s primetime slate after just one season. But not before the show became a darling of critics, won the Emmy for Outstanding Comedy Series, and earned Windom the only Emmy of his career, as Lead Actor in a Comedy Series.

They're Tearing Down Tim Riley's Bar

The second William Windom role that history has sadly let slip through the cracks is, of all things, a segment of Night Gallery, Rod Serling’s wildly uneven and critically panned anthology horror series, produced a decade or so after the demise of The Twilight Zone, his landmark achievement in post-McCarthy era mystery and allegory.

In They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar, written by Serling himself, Windom plays a middle-aged businessman and World War II vet who’s doing his best to work his way down the corporate ladder. His beloved wife has been dead many years, his job as a plastics salesman no longer fulfills him, and he has slowly, quietly turned into a broken, lonely man whose best days are behind him and whose only comfort is found in a glass and his memories of his favorite bar, a tavern called Tim Riley’s where he and his wife used to go in younger, happier days.

In They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar, written by Serling himself, Windom plays a middle-aged businessman and World War II vet who’s doing his best to work his way down the corporate ladder. His beloved wife has been dead many years, his job as a plastics salesman no longer fulfills him, and he has slowly, quietly turned into a broken, lonely man whose best days are behind him and whose only comfort is found in a glass and his memories of his favorite bar, a tavern called Tim Riley’s where he and his wife used to go in younger, happier days.

I will spare you all the details, but suffice to say the segment is a story of loss, loneliness, regret and the haunting, even crippling nature of memory. Windom is remarkable as he plays both lonely and defeated, yet does so without a trace of self-pity. His character is melancholy, but he’s also entirely at peace with that melancholy, and in an odd way that makes him fearless as he takes on both his frustrated boss and the aggressive, ambitious young newcomer who seeks to climb over him on his way to the top.

I will spare you all the details, but suffice to say the segment is a story of loss, loneliness, regret and the haunting, even crippling nature of memory. Windom is remarkable as he plays both lonely and defeated, yet does so without a trace of self-pity. His character is melancholy, but he’s also entirely at peace with that melancholy, and in an odd way that makes him fearless as he takes on both his frustrated boss and the aggressive, ambitious young newcomer who seeks to climb over him on his way to the top.

The “going home again” motif is ground that Serling traveled quite often in his Twilight Zone days, but not nearly so effectively as he does here. And in many ways he has Windom to thank for that. Because Windom takes what in the hands of a lesser actor could have easily become a sappy, maudlin, crestfallen character and transforms him into someone noble, even heroic.

The “going home again” motif is ground that Serling traveled quite often in his Twilight Zone days, but not nearly so effectively as he does here. And in many ways he has Windom to thank for that. Because Windom takes what in the hands of a lesser actor could have easily become a sappy, maudlin, crestfallen character and transforms him into someone noble, even heroic.

Shortly before his death, Rod Serling said the two greatest things he ever wrote had nothing to do with The Twilight Zone. They were the teleplays for Requiem for a Heavyweight and They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar. And I’m not so sure that, at least in the case of the latter, it wasn’t a combination of his words and what William Windom did with them that compelled him to feel that way.

To Kill a Mockingbird

in 2003, the American Film Institute named Atticus Finch of To Kill a Mockingbird the #1 heroic character in the history of American film. And very few who have ever seen the movie would take exception to that.

What’s more, my single favorite cinematic moment of all time is in the film. It's the scene in which the old black man, standing in the balcony at the trial, which led to an innocent young African American being railroaded into a conviction for raping a white woman despite Atticus’ best efforts, says to young Jean Louise Finch who’s on her knees and peering through the railing, “Miss Jean Louise. Miss Jean Louise, stand up." Then, after a long beat, he stands erect and adds with respectful dignity, "Your father’s passing.”

What’s more, my single favorite cinematic moment of all time is in the film. It's the scene in which the old black man, standing in the balcony at the trial, which led to an innocent young African American being railroaded into a conviction for raping a white woman despite Atticus’ best efforts, says to young Jean Louise Finch who’s on her knees and peering through the railing, “Miss Jean Louise. Miss Jean Louise, stand up." Then, after a long beat, he stands erect and adds with respectful dignity, "Your father’s passing.”

Yet, for as noble and as admirable as Atticus was, a big part of that nobility arose out of the stark contrast between him and many of the other men in and around Maycomb, Alabama, where the story is set. Among these is Mr. Horace Gilmer, Monroe County's arrogant young district attorney, played by Windom in what was to be his film debut.

And as I said, the contrast is remarkable. Atticus is well-groomed and mannerly, standing tall in his seersucker suit and seemingly oblivious to the wilting heat as he passionately pleads his case, oblivious to the fact the trial is just an exercise in procedure, that the fix is in, and that the die has been long since cast.

And as I said, the contrast is remarkable. Atticus is well-groomed and mannerly, standing tall in his seersucker suit and seemingly oblivious to the wilting heat as he passionately pleads his case, oblivious to the fact the trial is just an exercise in procedure, that the fix is in, and that the die has been long since cast.

Gilmer on the other hand is slovenly and disheveled, his hair unkempt, his tie askew, and his posture a combination of sullen and insolent. He often acts bored and watches the proceedings while leaning back in his seat, a pen hanging out of his mouth like a drunkard's swizzle stick. He’s already won and he knows it. He’s just wondering what time he can get out of there.

Gilmer on the other hand is slovenly and disheveled, his hair unkempt, his tie askew, and his posture a combination of sullen and insolent. He often acts bored and watches the proceedings while leaning back in his seat, a pen hanging out of his mouth like a drunkard's swizzle stick. He’s already won and he knows it. He’s just wondering what time he can get out of there.

Truth be told, Windom didn’t have much to do in the film, and had relatively few lines. Yet his creepy performance was just one more brick in the wall as Robert Mulligan, Gregory Peck, and a bunch of character actors, unknowns and first-timers somehow and with little fanfare managed to do something that hadn’t been done since the days of Gone With the Wind; turn a celebrated, deeply loved best-selling Southern novel into an equally celebrated and far more beloved movie.

And even though most people will no doubt soon forget the name William Windom, they’ll watch him for as long as people watch movies. For as long they watch movies, they’ll watch To Kill a Mockingbird.

And even though most people will no doubt soon forget the name William Windom, they’ll watch him for as long as people watch movies. For as long they watch movies, they’ll watch To Kill a Mockingbird.

And when they do, they’ll behold a self-proclaimed journeyman actor who in his very first film role, and in his own unique way, helped define Atticus Finch as a giant of a man; a actor thanklessly playing opposite the great Gregory Peck as a drawling, small-minded racist; and an actor who for generations to come will give weight, depth and texture to Atticus' nobility by remaining forever smug, forever hateful, and forever chewing that pen of his.