A few years ago when Fleetwood Mac was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and he found himself excluded from the exhibit that listed the band’s lineup and former members, Bob Welch jokingly chided himself for being “the invisible man.”

A few years ago when Fleetwood Mac was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and he found himself excluded from the exhibit that listed the band’s lineup and former members, Bob Welch jokingly chided himself for being “the invisible man.”

Yet the irony was that while Welch may have been kidding about the extent to which the Hall of Fame, if not all of pop culture, has dismissed the role he played in helping Fleetwood Mac become an international sensation, for a number of observers -- myself included -- he remains the one guy without whom the only way the rest of the band might have ever gained entry into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame was to pay admission.

Because, outside of the two guys from whom the band derived its name – drummer Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie – the single most historically important member of Fleetwood Mac was probably Bob Welch. Or at the very least, he was its most historically overlooked.

But more on that later. First some background.

But more on that later. First some background.

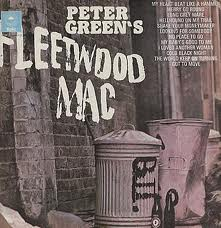

By now, many know the story. In the late Sixties, Fleetwood Mac emerged as an offshoot of John Mayall and his Bluesbreakers when guitar wiz Peter Green left Mayall, hooked up with Fleetwood and McVie, and formed a straight-forward, hard-rocking, London-based quartet that scored some radio play with a few of their songs, one of which was an entirely out-of-character, melodic instrumental titled Albatross that somehow shot to the top of the British pop charts.

Yet because Fleetwood Mac, behind its headstrong and often mercurial lead guitarist, remained steadfastly committed to its blues roots, from 1967 through 1970 the band remained little more than a niche musical act attracting a small, almost snobbish legion of blues purists.

As a result, the band’s first three albums, while achieving critical acclaim, were commercial flops. And their fourth didn’t sell much better. Titled Kiln House, the disc was an uneven mix of blues and melodic pop riffs, the latter thanks in large part to two relatively new players, an amazingly talented lead guitarist named Danny Kirwan, and a part-time background singer named Christine Perfect, who would soon join the band as its keyboardist, marry its bass player, and take his last name. But thanks to Kirwan and Chrissy McVie, the album marked an ever-so-subtle musical shift for Fleetwood Mac.

But it was not until their fifth LP that Fleetwood Mac started to morph into something more than just another hard-rocking British blues band. And that happened by attrition as much as anything else.

But it was not until their fifth LP that Fleetwood Mac started to morph into something more than just another hard-rocking British blues band. And that happened by attrition as much as anything else.

Green, the guitar virtuoso who danced to the beat of his own drummer and who served as Fleetwood Mac’s front man for years, had been slowly going insane and by the release of their fourth album was rumored to be living in a cave.

Another purist and note-bending guitarist, Jeremy Spencer, told the rest of the band he was going out for a magazine one day, met up with a religious cult called the Children of God, joined them and never came back.

And the ferociously talented Kirwan, who even though he was just 19, was already drinking daily and brooding heavily, and had clearly passed the point of no return on his personal road to addiction and substance abuse.

So Fleetwood Mac found itself in desperate need of a guitarist to support the increasingly unpredictable Kirwan, and on the basis of a single phone call and a couple of brief meetings – and never once hearing him play – Fleetwood and McVie hired Welch, a Los Angeles-born rhythm guitarist who had come recommended to them, and who at the time was living hand-to-mouth, sleeping on floors, and playing with a power pop trio he’d joined across the Channel in Paris.

So Fleetwood Mac found itself in desperate need of a guitarist to support the increasingly unpredictable Kirwan, and on the basis of a single phone call and a couple of brief meetings – and never once hearing him play – Fleetwood and McVie hired Welch, a Los Angeles-born rhythm guitarist who had come recommended to them, and who at the time was living hand-to-mouth, sleeping on floors, and playing with a power pop trio he’d joined across the Channel in Paris.

And it was with Future Games, their fifth album and first with Welch, that Fleetwood Mac threw off the last vestiges of its humble blues origins and moved off into a far more melodic and pop-fueled direction. The album was not great by any means, but it established the band as one with a strong sense of melody and the ability to mix light, almost jazzy melodic hooks with a clear pop vision.

The record also helped Fleetwood Mac define what would become its two main voices for a five-album march toward what they hoped would be mainstream acceptance; the raspy, almost-whispering California cool of Welch and the angelic, even slightly operatic milk-and-honey warbling of Ms. McVie. What’s more, Welch and McVie became the band’s most dependable songwriters and started churning out a string of remarkably catchy pop tunes, album after album for four straight years.

The record also helped Fleetwood Mac define what would become its two main voices for a five-album march toward what they hoped would be mainstream acceptance; the raspy, almost-whispering California cool of Welch and the angelic, even slightly operatic milk-and-honey warbling of Ms. McVie. What’s more, Welch and McVie became the band’s most dependable songwriters and started churning out a string of remarkably catchy pop tunes, album after album for four straight years.

Unfortunately none of those five sold a damn, particularly in the U.S. And Fleetwood Mac remained for an almost four year stretch between 1971 and early 1975 little more than a cult band whose listeners were relegated to a bunch of AOR stations in markets and college towns across the States, many of whom had been lured in by two Welch originals; Sentimental Lady off of the band’s follow up to Future Games, Bare Trees, and the band’s most widely played FM radio hit to that point, Hypnotized, from its fourth disc with Welch, Mystery to Me.

It was during this five album bridge between what they had once been and what they were about to become that Welch suggested to the other members that they relocate to the States. The band couldn’t fall out of a boat and hit water in England, but was starting to gain a measure of popularity in America. And Welch, whose mother had been a Hollywood night club singer and actress and whose father had produced such Bob Hope hits as The Lemon Drop Kid, The Paleface and Son of Paleface, was fully aware of what being based in L.A. could mean to the band’s fortunes.

Unfortunately, right around that very time things just started falling apart for Fleetwood Mac.

Unfortunately, right around that very time things just started falling apart for Fleetwood Mac.

One night while on tour, Kirwan got drunk, left the stage in the middle of a show, and never came back. The band was left with no choice and Kirwan became yet another in a long line of ex-Fleetwood Mac guitarists.

At another point, the band’s manager, unable to come to terms with the group over the specifics of a planned record tour, went ahead with the tour anyway, believing he had the rights to the band’s name. He merely hired another band and re-christened it Fleetwood Mac. Suddenly the band was not only in court, but all over the music press, making headlines for all the wrong reasons.

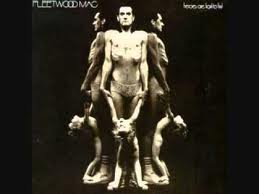

And Welch had grown utterly exhausted from assuming what had become the lion’s share of the singing and songwriting duties for Fleetwood Mac. On his final album with the band, Heroes Are Hard to Find, he wrote and sang no less than 7 of the 11 songs. He had also, with the departure of Kirwan, become the band's last remaining guitarist. And on top of all that, his marriage began crumbling right before his eyes. So suddenly and without warning, Bob Welch quit.

Fortunately for Fleetwood and McVie, when they went looking for a replacement, since they were now living in California they caught wind of a brilliant singer/guitarist named Lindsey Buckingham up the coast in San Francisco. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Fortunately for Fleetwood and McVie, when they went looking for a replacement, since they were now living in California they caught wind of a brilliant singer/guitarist named Lindsey Buckingham up the coast in San Francisco. And the rest, as they say, is history.

So indirectly, while Welch may have left Fleetwood and McVie high and dry, it was because he brought them to the U.S. in the first place, and specifically to California, that they were able to meet Buckingham and his partner Stevie Nicks, that they were in a position to invite both to join the band, and they were able to assemble the Fleetwood Mac lineup that in a few short years would go on to outsell all but a handful of artists in the history of music.

After leaving Fleetwood Mac, Bob Welch subsequently had the briefest of runs as a solo artist, but truth be told he was never the same without the structure of a band, or without the studio magic that seemed to bubble up whenever he, Christine McVie and the others starting blending their talents over a cauldron of new songs. And one need look no further than Sentimental Lady, a lilting ballad Welch originally wrote for Bare Trees, and then rerecorded five years later for his solo debut, French Kiss.

After leaving Fleetwood Mac, Bob Welch subsequently had the briefest of runs as a solo artist, but truth be told he was never the same without the structure of a band, or without the studio magic that seemed to bubble up whenever he, Christine McVie and the others starting blending their talents over a cauldron of new songs. And one need look no further than Sentimental Lady, a lilting ballad Welch originally wrote for Bare Trees, and then rerecorded five years later for his solo debut, French Kiss.

As played by Fleetwood Mac, circa 1972, the original Sentimental Lady is light and airy and flits like sunbeams off a prism. But when Welch laid the tune down a second time – even with the presence of talented artists like Buckingham and Chrissy McVie – the net result ended up sounding plodding and mechanical and it didn’t so much dart in and out of the rafters as much as it lumbered beneath one’s feet, all leaden and earthbound.

So much so, in fact, that when I bought French Kiss when it first came out, and played it once, I never bothered to play it again.

It’s hard to explain what made Bob Welch such an intriguing artist when he was with Fleetwood Mac some four decades ago. There was nothing about him that screamed brilliance or demanded that the listener sit up and take notice. He was not a great singer and was nothing more than a serviceable guitar player. His lyrics could be clunky, sophomoric and at times lacking any real sense of poetry or lyrical balance, and they often exhibited a half-baked sort of pop spirituality and pulp mysticism that, especially to hear them these days, could be downright cringe-inducing.

It’s hard to explain what made Bob Welch such an intriguing artist when he was with Fleetwood Mac some four decades ago. There was nothing about him that screamed brilliance or demanded that the listener sit up and take notice. He was not a great singer and was nothing more than a serviceable guitar player. His lyrics could be clunky, sophomoric and at times lacking any real sense of poetry or lyrical balance, and they often exhibited a half-baked sort of pop spirituality and pulp mysticism that, especially to hear them these days, could be downright cringe-inducing.

But Welch had a knack for writing melodic, ethereal pop hooks that could be, if you’ll forgive me, utterly hypnotic. And he wrote songs that every once in a while included a chord or two, or even a collection of notes, that sounded so unlike anything else you’d ever heard before, you’d swear he’d either just made them up on the spot or stumbled upon them by chance.

And maybe that’s why so many critics seemed to have a problem with him. Almost everything Welch did during his Fleetwood Mac era seemed to be self-taught and lacking any sense of traditional form and structure. And his jazzy brand of rock appeared to adhere to a set of rules that only he knew, and quite often it meandered off into places that were almost impossible to anticipate, if not follow.

And maybe that’s why so many critics seemed to have a problem with him. Almost everything Welch did during his Fleetwood Mac era seemed to be self-taught and lacking any sense of traditional form and structure. And his jazzy brand of rock appeared to adhere to a set of rules that only he knew, and quite often it meandered off into places that were almost impossible to anticipate, if not follow.

But somehow it worked, and frankly so much of it still does.

And above all, there remains to this day something about many Bob Welch songs during his Fleetwood Mac days that feel refreshingly honest and somehow tethered to a place deep within the man. And I listen to them today and they still retain their emotional power and their ability to transport me to another place and time.

There's no doubt that Bob Welch, for all this shortcomings as an artist, should be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, alongside his fellow Fleetwood Mac mates. He's earned that honor, and then some.

There's no doubt that Bob Welch, for all this shortcomings as an artist, should be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, alongside his fellow Fleetwood Mac mates. He's earned that honor, and then some.

I was glad to hear that after years of telling anyone who would care to listen that his exclusion to the Hall was because he and Fleetwood Mac were locked in a lawsuit over royalties, that the suit had been settled, that he’d been invited backstage by the band not that long ago, and that they’d found a way to bury the hatchet.

I was glad too that he’d spent his final years singing a different tune; saying that his being left out of the Hall was not so much a matter of the band’s choice, but that of the selection committee, a group of rock snobs which included some of his harshest critics.

Bob Welch had some major spinal surgery not all that long ago. In declining health, he apparently placed a gun to his chest last Thursday and pulled the trigger. He left a suicide note that said he loved his wife but that he didn’t want to put her in the position of having to care for an invalid.

Bob Welch had some major spinal surgery not all that long ago. In declining health, he apparently placed a gun to his chest last Thursday and pulled the trigger. He left a suicide note that said he loved his wife but that he didn’t want to put her in the position of having to care for an invalid.

I never saw him perform live. But I did see the Fleetwood Mac tour to support the band’s stunning self-titled album in 1975, a tour which served both as a coming out party for Buckingham and Nicks and as one of the first steps on a road that would lead band into to the musical stratosphere.

And while I was delighted with much of that show so many years ago, I’ll never forget its encore – Lindsey Buckingham singing and playing the song that got the biggest rise out of the crowd that evening, and frankly the biggest rise by far; Bob Welch’s Hypnotized.

Nor will I ever forget what I learned in my research for this piece you’re reading now; that of all Welch’s former band mates who were moved by his death, no one was more taken aback than, of all people, Stevie Nicks, who said she was torn up when she’d heard Welch had passed. "The death of Bob Welch is devastating,” Nicks told the AP. “I had many great times with him after Lindsey and I joined Fleetwood Mac. He was an amazing guitar player. He was funny, sweet, and he was smart. I am so very sorry for his family and for the family of Fleetwood Mac." She then tailed off, saying simply, "So, so sad...”

Nor will I ever forget what I learned in my research for this piece you’re reading now; that of all Welch’s former band mates who were moved by his death, no one was more taken aback than, of all people, Stevie Nicks, who said she was torn up when she’d heard Welch had passed. "The death of Bob Welch is devastating,” Nicks told the AP. “I had many great times with him after Lindsey and I joined Fleetwood Mac. He was an amazing guitar player. He was funny, sweet, and he was smart. I am so very sorry for his family and for the family of Fleetwood Mac." She then tailed off, saying simply, "So, so sad...”

The world may not remember Bob Welch, the guy who Mick Fleetwood in his autobiography credits with "saving Fleetwood Mac." But in a very real way, thanks to a brief and occasionally inspired run he once had, it will never forget the band he used to call home.

A Bob Welch Primer

A Bob Welch Primer

While Bob Welch recorded a total of five albums with Fleetwood Mac, he really hit his stride during the last four of them. Here are four Bob Welch tunes you should really get to know, one from each of the final four albums he did with the group, along with a few reflections on each.

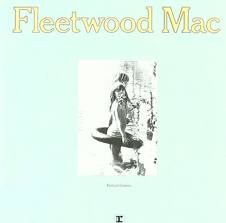

Sentimental Lady (1972)

At first blush, the difference between the gently melodic version of Sentimental Lady on Bare Trees and the heavy-handed remake on French Kiss would appear to be the backbeat established by the rhythm section of Fleetwood and McVie. But in reality, the biggest difference between the two is the understated and stunning guitar of Kirwan, who remains Bare Trees’ unsung hero. And speaking of unsung, as I was writing this it stuck me: outside of perhaps Sgt. Pepper's, I'm not sure any rock album's cover art ties together any more subtly, any more profoundly, or any more thematically than the chilly winter scene on the cover of Fleetwood Mac’s 1972 minor masterpiece.

Bright Fire (1973)

One of the saddest things about Welch’s decision to take his one life in such a graphic manner is the combination of innocence, spirituality and hope inherent in so many of the lyrics he penned as a young artist. On the written page, Bright Fire is a hodgepodge of visual images and lyrical phrases that seem to exist for little or no purpose. But when sung beneath the song’s haunting chord progression, and then punctuated by its wistfully romantic coda, the effect is mesmerizing. It’s far from Bob Welch’s best pop tune, but it’s remarkably beautiful one that has the unique ability to make almost any first-time listener at some point look in the direction of the music and ask simply, “Who is that?”

Hypnotized (1973)

If Albatross was the song that put Fleetwood Mac on the map in England, Hypnotized was the one who turned that trick in the U.S. A jazzy, slightly bluesy groovefest that overcame some pretty awful lyrics to emerge as an FM classic, the song rides Fleetwood’s repetitive, triple-time drumming, Bob Weston’s less-is-more guitar and one of the most contagious hooks in rock history to establish an unmistakable mood of dreamlike reverie. Ironically, Weston was the only other full-time Mac member excluded from the Hall of Fame; the difference being Weston earned his place on the outside looking in. During the making of Mystery to Me, the guitarist had a steamy affair with Fleetwood’s wife, devastating the drummer, ruining his marriage, and almost destroying the band.

Silver Heels (1974)

By the time they laid down Heroes are Hard to Find, Fleetwood Mac was down to one guitarist, and Welch had emerged as the band's chief cook and bottle washer. His final Fleetwood Mac album contained the usual Welch fare; a few billowy numbers and one excessively mystical one. But it also contained one of the greatest pop songs the band ever committed to vinyl, featuring one of the catchiest, most fun-loving choruses they ever recorded. Silver Heels tells the story of a young man’s impromptu rendezvous with an older, more worldly woman, and it is part praise for how she’s opened his eyes to a world beyond his own and part lament for not being all the things a man needs to be to keep such a woman. Bob Welch might have written a more widely acclaimed pop song in his day, but he never wrote a better one.