I guess without realizing it, I grew up on country music. As a kid, I always had country songs listed among my favorites – songs like Claude King’s Wolverton Mountain, From a Jack to a King by Ned Miller, Roger Miller’s King of the Road, and two of my all-time faves, both by Don Gibson, Oh Lonesome Me and Sea of Heartbreak.

I guess without realizing it, I grew up on country music. As a kid, I always had country songs listed among my favorites – songs like Claude King’s Wolverton Mountain, From a Jack to a King by Ned Miller, Roger Miller’s King of the Road, and two of my all-time faves, both by Don Gibson, Oh Lonesome Me and Sea of Heartbreak.

It’s just that until I got older and realized they had crossed over onto the pop charts, I had no idea that they actually were country.

It’s just that until I got older and realized they had crossed over onto the pop charts, I had no idea that they actually were country.

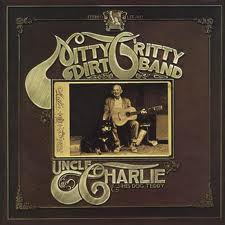

Then as I got a little older still and started buying albums, I stumbled onto Uncle Charlie and his Dog Teddy by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, mostly because at the time I was trying to teach myself the harmonica and was drawn to their harp player, Jimmy Fadden.

And it was the Dirt Band that led me to what I now realize was a seminal moment in my development as a country music lover.

And it was the Dirt Band that led me to what I now realize was a seminal moment in my development as a country music lover.

Not the kind of crossover country I had been brought up on, mind you, or the kind of hybrid, multiple-guitar country-rock that got popular in my college years, thanks to bands like the Allman Brothers, Marshall Tucker and any number of their lukewarm imitatators. Not the kind of country that made a brief comeback in the 80’s, led by a group of big-hatted beefcakes that critics at the time were calling, “neo-traditionalists.” And heaven forbid, not the kind of redneck pop that’s passing itself off as country these days.

But real roots country; the kind played a century ago by farmers on their front porch after a long day in the field. The brand that got passed on to pickers by their fathers, who’d also been pickers, who’d learned at the knees of their fathers, who’d likewise been pickers. The kind that to a certain ear could sound as sweet new-mowed hay and as kick-ass as swig of home-brew – often at the same time.

But real roots country; the kind played a century ago by farmers on their front porch after a long day in the field. The brand that got passed on to pickers by their fathers, who’d also been pickers, who’d learned at the knees of their fathers, who’d likewise been pickers. The kind that to a certain ear could sound as sweet new-mowed hay and as kick-ass as swig of home-brew – often at the same time.

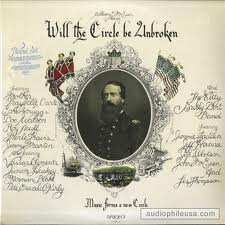

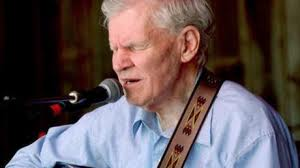

In 1972, the year I graduated from high school, I got in the mail from my record club one day the Dirt Band’s follow up to Uncle Charlie. It was a two-record disc called Will the Circle Be Unbroken, and it featured a number of musical guests, including some apparent country legends, people like Mother Maybelle Carter, Earl Scruggs, Merle Travis and a guy named Doc Watson.

And unlike most albums in which the musical guest played a supporting role, on Circle it was the Dirt Band that took a step back and ceded center stage, leaving their country guests to drive the train, so to speak.

And unlike most albums in which the musical guest played a supporting role, on Circle it was the Dirt Band that took a step back and ceded center stage, leaving their country guests to drive the train, so to speak.

At first I was jarred. The album was far too raw and unvarnished for my young tastes. There was no pristine production. No army of supporting musicians. Its harmonies didn’t sound like they’d been put into a blender by a producer, who’d then hit puree. And it didn't even feature the band I bought the album for in the first place.

What's more, it just didn’t feel like a finished product. Hell, some songs didn’t even sound like they were recorded in a studio. They sounded like they were recorded by a bunch of guys sitting around somebody's kitchen table having a good time, and each cut included not just words and music, but some of the dialogue in between.

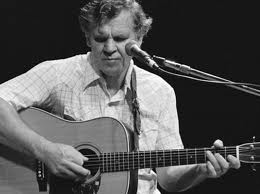

I swear I wouldn’t have given Will the Circle Be Unbroken a second listen, if not for one song. It was a jumpy little tune titled Tennessee Stud and one that was sung by Watson, who also played lead guitar.

I swear I wouldn’t have given Will the Circle Be Unbroken a second listen, if not for one song. It was a jumpy little tune titled Tennessee Stud and one that was sung by Watson, who also played lead guitar.

When I heard Tennessee Stud the first time my ears pricked up. So I lifted the tone arm and I played it again. Then I did it again.

There was something about not so much the song as the guy’s voice and his guitar picking that did something profound to me. I couldn’t explain it, but the guy seemed to transport my young mind to another place and time and opened it to not merely a whole new set of possibilities, but an entirely new world; one that was apparently here long before I was.

I truly had never heard anything quite like him.

It was like I had spent my entire musical life on training wheels, and suddenly here came this guy – this very real, largely unassuming and remarkably human-sounding voice – saying to me and my still young ears, “Son, let’s try it this time without the training wheels, OK?”

It was like I had spent my entire musical life on training wheels, and suddenly here came this guy – this very real, largely unassuming and remarkably human-sounding voice – saying to me and my still young ears, “Son, let’s try it this time without the training wheels, OK?”

That was Doc Watson, and that’s what he meant to me and my musical development. And it was Watson who with that one song started me down a musical path that would eventually lead me to everything from the genius of Hank Williams and the stunning virtuosity of Jerry Douglas, to the honky tonk ken of Billy Joe Shaver and the soul-cleansing harmonies of the Delmore Brothers.

Believe me; I will never be able to thank him enough.

I never really did mine Doc’s entire catalog to the extent that I probably should have. But he was always there as I continued to my lifelong musical journey, like when he graced one of my favorite albums, Maria Muldaur’s Waitress in a Donut Shop, and lent her Honey Babe Blues a layer of authenticity I doubt it would have ever achieved without him.

I never really did mine Doc’s entire catalog to the extent that I probably should have. But he was always there as I continued to my lifelong musical journey, like when he graced one of my favorite albums, Maria Muldaur’s Waitress in a Donut Shop, and lent her Honey Babe Blues a layer of authenticity I doubt it would have ever achieved without him.

But I guess that’s the way it always was with Doc, a simple North Carolina boy and the son of a dirt farmer who chose never to stray far from his humble roots. Whenever some artist needed someone to make the rest of his or her project seem just a little more authentic, or a little more truthful, there would be  Doc singing, picking, and in his own way keeping the whole affair grounded.

Doc singing, picking, and in his own way keeping the whole affair grounded.

I’m sure the man never made the kind of money his enormous talent should have afforded him. And I know he never achieved the kind of acclaim that was his due.

And I know too he had a few really tough breaks in life, like when he lost his sight at age one to a virus, or when he lost his beloved son and playing partner Merle to an oddly poetic but still tragic tractor accident.

But Watson somehow got through it, and managed to do what folks did where he grew up. He learned to abide. And found a way to matter. That’s why roots music lovers the world over found something in Doc Watson they were inexorably drawn to and eternally comfortable with.

But Watson somehow got through it, and managed to do what folks did where he grew up. He learned to abide. And found a way to matter. That’s why roots music lovers the world over found something in Doc Watson they were inexorably drawn to and eternally comfortable with.

Maybe that’s also why a few years ago he was honored with a statue in Boone, North Carolina, near his farm, and why the bronze likeness was not cast in a standing position or placed in the center of town, but seated on a park bench under a shade tree, eyes closed and picking a guitar.

And maybe that’s why below his name, on the plaque next to the statue, the town fathers chose not some lofty piece of prose or high-minded quote to honor their favorite son, but instead were able to distill the essence of what he meant to them and just about anyone who had ever heard him in five simple words: “Just one of the people.”

And maybe that’s why below his name, on the plaque next to the statue, the town fathers chose not some lofty piece of prose or high-minded quote to honor their favorite son, but instead were able to distill the essence of what he meant to them and just about anyone who had ever heard him in five simple words: “Just one of the people.”

For everything you showed a young man way back when, and for all the musical discoveries you helped make possible along the way, thank you Doc. And keep pickin'.