When I was a kid my father used to say that if you stood on the corner of 42nd Street and Broadway in New York long enough, eventually everyone you know would pass you by. It’s not quite the same thing, but I feel sometimes that the Patio Area in the right field corner of what for years used to be called Comiskey Park on the South Side of Chicago serves a somewhat similar function in my baseball life.

When I was a kid my father used to say that if you stood on the corner of 42nd Street and Broadway in New York long enough, eventually everyone you know would pass you by. It’s not quite the same thing, but I feel sometimes that the Patio Area in the right field corner of what for years used to be called Comiskey Park on the South Side of Chicago serves a somewhat similar function in my baseball life.

At least in terms of baseball people, the place is both a beehive and a crossroads.

If you’ve ever seen a White Sox broadcast on local TV, you’ve no doubt heard Hawk Harrelson urging fans to bring a group out to the Patio Area to enjoy a little pre-game meal with the “Bertucci Boys.” Those “boys” Hawk is referring to in his folksy but deeply appreciated on-air plugs would be Bob and Bruno Bertucci, who along with brother Carmen, sister Eva, a few sons and daughters, a number of nieces, nephews and in-laws, and countless others in and around their home neighborhood of Bridgeport, put on a terrific spread before each Sox home game.

If you’ve ever seen a White Sox broadcast on local TV, you’ve no doubt heard Hawk Harrelson urging fans to bring a group out to the Patio Area to enjoy a little pre-game meal with the “Bertucci Boys.” Those “boys” Hawk is referring to in his folksy but deeply appreciated on-air plugs would be Bob and Bruno Bertucci, who along with brother Carmen, sister Eva, a few sons and daughters, a number of nieces, nephews and in-laws, and countless others in and around their home neighborhood of Bridgeport, put on a terrific spread before each Sox home game.

And they’ve been doing that for what I’m stunned to realize is 35 years.

And while I’m technically an employee of their company, Baseball Buffet, which they started a long time ago on a bar napkin, and every so often help them when they’re short-handed, what I really am is a 35-year friend who first met them when all three of us were a lot younger and a whole lot more reckless, but who still likes to visit the Patio whenever he feels the need to re-energize and find himself among family.

I bring it up because two news items I heard about this week led me immediately to think, of all things, the Patio -- or at least two encounters I had out there. The first item, strangely enough, was the Tigers' release of Brandon Inge.

I bring it up because two news items I heard about this week led me immediately to think, of all things, the Patio -- or at least two encounters I had out there. The first item, strangely enough, was the Tigers' release of Brandon Inge.

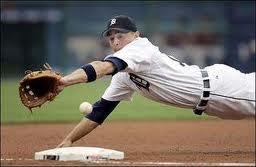

Brandon Inge was one of those baseball players who, even if he was hitting .200 – which honesty compels me to admit, he often was – you’d still find yourself constantly watching throughout a game. He was simply a stunning athlete. Not visually powerful, or even particularly fast, he had a physical grace and a fluid way of moving on the diamond that dared you not to take notice. And every so often he’d make a play with the glove that could downright take your breath away. In fact, in 2006 ESPN called a diving stop and throw he made at 3B its Play of the Year at that position.

And Inge was a gamer in every sense of the word. When he came out of unheralded Virginia Commonwealth University in 1998, he did so as a shortstop. But not just any shortstop. When the game was on the line and the VCU coach would call for his closer, what he really had to summon for was an infielder because his closer was already in the game at short.

And Inge was a gamer in every sense of the word. When he came out of unheralded Virginia Commonwealth University in 1998, he did so as a shortstop. But not just any shortstop. When the game was on the line and the VCU coach would call for his closer, what he really had to summon for was an infielder because his closer was already in the game at short.

I guess it’s not hard to imagine Inge during some game along the way, when the coach was looking for a pitcher who could get the last out, telling him, “Skip, I can do that.” And time after time, that’s exactly what he did.

When the Tigers drafted Inge in the second round in the ’98 draft, he switched positions and became, of all things, a catcher.

When the Tigers drafted Inge in the second round in the ’98 draft, he switched positions and became, of all things, a catcher.

At first blush having such a graceful athlete, especially a small, wiry one, toiling away behind the plate in a position often occupied by the thickest, slowest and least mobile players on the roster would seem a little like having a race horse pull a plow. But Inge brought something special to the position with his cat-like reflexes, hair-trigger release and cannon of an arm.

He also might have been as active and as engaged as any catcher I have ever seen play. That, not his offense, was probably why he got to the big leagues in less than three years.

But what I really loved about Inge was his unassuming, selfless nature and that whole “Skip, I can do that” attitude of his. That’s why when the Tigers signed future Hall of Famer Pudge Rodriguez to catch in 2004, and Inge suddenly found himself without a starting job, he became the Tigers’ utility man extraordinaire that season and started multiple games at five different positions for the club. Then the following year when the Tigers needed a 3B, he looked around and said, “Skip, I can do that.” And he did.

When he was designated for assignment last summer, and in essence found himself in a position to be either traded or released, he agreed to go to the minor leagues – not, mind you, all that long after having represented the American League in the All Star Game and competing in the Home Run Derby (where, not surprisingly, he became one of the few players in history to fail to hit even a single HR).

When he was designated for assignment last summer, and in essence found himself in a position to be either traded or released, he agreed to go to the minor leagues – not, mind you, all that long after having represented the American League in the All Star Game and competing in the Home Run Derby (where, not surprisingly, he became one of the few players in history to fail to hit even a single HR).

This spring, the Tigers signed free agent Prince Fielder to play 1B and made perennial All Star (and incumbent 1B) Miguel Cabrera their starting 3B, leaving Inge once again without a job. After taking a few days to lick his wounds, the long-time Tiger jack-of-all-trades realized the club needed a 2B and once again told his manager, “Skip I can do that.” And for a very brief time, he did.

But the bat would always be a problem for Inge, and it would eventually cost him his Tiger career. At the time of his release he had a lifetime BA of .234 over the course of 12 full and partial seasons, half of which ended up with him hitting .210 or less.

But the bat would always be a problem for Inge, and it would eventually cost him his Tiger career. At the time of his release he had a lifetime BA of .234 over the course of 12 full and partial seasons, half of which ended up with him hitting .210 or less.

In fact, his lack of hitting so frustrated fans in the Motor City over the course of his mostly up-and-down run as a Tiger that many of them, perhaps looking only at his batting average, would boo when his name was announced. And as a result, despite the fact Brandon Inge bought a home and raised a family in Detroit and lived there his entire career, including the off-season, despite the man’s unabashed love for the city and his willingness to give to local charities like few athletes ever have, despite returning from his demotion to the minor league to not only hit two walk off HRs for the Tigers that September, but win MLB’s Man of the Year Award, and despite all the intangibles and the stunning glove work he constantly brought to bear, his often anemic bat turned him into one of the most polarizing Tiger figures since Denny McLain (or at very least, Bo Schembechler).

I thought of the Patio when I heard of Inge’s release two days ago because once in the summer of 2005 I was out there before a game and ran into Tiger president Dave Dombrowski, who I used to work with many years ago when Bill Veeck owned the Sox. David and I started talking baseball as we usually do when we see each other, and I said to him at one point, “David, I have to admit it, I think your boy Brandon Inge just might be my favorite player in all of baseball. I gotta tell ya', I just love watching the guy play.”

I thought of the Patio when I heard of Inge’s release two days ago because once in the summer of 2005 I was out there before a game and ran into Tiger president Dave Dombrowski, who I used to work with many years ago when Bill Veeck owned the Sox. David and I started talking baseball as we usually do when we see each other, and I said to him at one point, “David, I have to admit it, I think your boy Brandon Inge just might be my favorite player in all of baseball. I gotta tell ya', I just love watching the guy play.”

David’s face lit up and he said chuckling, “Really?” He then proceeded to sit down and tell me what an amazing athlete that the 5’11” 180-lb. Inge was and regaled me with examples of the guy’s amazing athletic prowess, including his being able to drive a golf ball almost 400 yards and the fact he could dunk a basketball with either hand. “You know, he’s probably the best fielder on our club at every position out there, including center field,” he added. At the time Dombrowski's CF was Curtis Granderson.

I’m sure it tore up David to have to tell Inge this week he was releasing him, as I’m sure saying goodbye to Inge was tough on his manager, Jim Leyland. I saw the emotion in each man’s eyes as each spoke on camera in hushed tones about a guy each of them clearly respected and admired, but a guy whose time had come and a player who had fallen prey to the harsh, unforgiving nature of the Major League roster limit.

I’m sure it tore up David to have to tell Inge this week he was releasing him, as I’m sure saying goodbye to Inge was tough on his manager, Jim Leyland. I saw the emotion in each man’s eyes as each spoke on camera in hushed tones about a guy each of them clearly respected and admired, but a guy whose time had come and a player who had fallen prey to the harsh, unforgiving nature of the Major League roster limit.

He may not have been a Hall of Famer, or for that matter even an above average baseball player. But my sense is someday even his detractors will embrace Brandon Inge in a way they never have before and celebrate him for what he truly was; one of the most fun-to-watch athletes of his day and one of the most giving, grounded young men ever to grace a Tiger uniform.

And speaking of the Patio and passings this week, I have to admit I was deeply saddened to hear that yesterday Bill “Moose” Skowron finally lost his long and courageous battle against lung cancer.

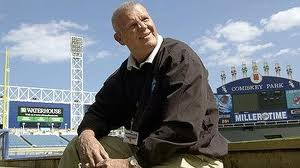

In his day, Moose, a Polish boy from the North Side of town, was a feared slugger and a key member of the powerful Yankee teams of the late Fifties, for whom he would eventually become a World Series legend. What’s more, he was an absolute terrific story teller and had a unique way of relating the most risqué tale in a humorous and thoroughly enjoyable, but by-and-large PG sort of way.

In his day, Moose, a Polish boy from the North Side of town, was a feared slugger and a key member of the powerful Yankee teams of the late Fifties, for whom he would eventually become a World Series legend. What’s more, he was an absolute terrific story teller and had a unique way of relating the most risqué tale in a humorous and thoroughly enjoyable, but by-and-large PG sort of way.

On more than one occasion I heard Moose say as much as he loved slugging the Yankees to a stunning comeback victory over the Milwaukee Braves in the ’58 World Series, the Series memory he would carry with him throughout life -- and one that continued to haunt him to the very end -- was from '63 when he hit .385 with a HR to help lead the team to which he’d been traded, the Los Angeles Dodgers, to a sweep over his beloved Yankees and a number of his dear friends still on the team. "I was miserable," he would say later in the book, Bombers, An Oral History of the New York Yankees.

On more than one occasion I heard Moose say as much as he loved slugging the Yankees to a stunning comeback victory over the Milwaukee Braves in the ’58 World Series, the Series memory he would carry with him throughout life -- and one that continued to haunt him to the very end -- was from '63 when he hit .385 with a HR to help lead the team to which he’d been traded, the Los Angeles Dodgers, to a sweep over his beloved Yankees and a number of his dear friends still on the team. "I was miserable," he would say later in the book, Bombers, An Oral History of the New York Yankees.

You see, more than anything else, the guy everyone who ever knew him called simply "Moose" was a terrific guy, a fiercely loyal friend and teammate, and the gentlest and most compassionate man you'd ever hope to meet. And I knew that because had gotten to know him, at least to say hello to and make small talk with, while he was working for the Sox in their community relations department.

You see, more than anything else, the guy everyone who ever knew him called simply "Moose" was a terrific guy, a fiercely loyal friend and teammate, and the gentlest and most compassionate man you'd ever hope to meet. And I knew that because had gotten to know him, at least to say hello to and make small talk with, while he was working for the Sox in their community relations department.

In Moose’s case, “community relations” meant that during every Thursday afternoon home game he would – and I kid you not – call Bingo matches for a small but loyal group of senior citizens in the Patio.

And for 13 years Moose loved calling those Bingo matches, and those Bingo-playing South Siders returned the feeling in-kind.

When Moose first contracted lung cancer I took it to heart, because not only did I come to truly love him as a person, but years ago my own father died of the very same disease. And because my dad had succumbed so quickly, I just assumed it would not be long for Moose.

That’s why on one particular Thursday last summer, months after I had heard just how sick he was, I was absolutely delighted to see Moose all alone walking at a snail’s pace through the Patio toward the corner tables we set aside for Bingo.

I remember racing up to him almost unable to contain my joy at seeing him looking so hale and hearty under the circumstances. We talked for a few moments and he then apologized and told me he had to get to work. Moose then shuffled off toward the Bingo tables.

I remember racing up to him almost unable to contain my joy at seeing him looking so hale and hearty under the circumstances. We talked for a few moments and he then apologized and told me he had to get to work. Moose then shuffled off toward the Bingo tables.

It would be the last time I would ever see him.

And when I heard he has passed yesterday, for a moment I thought of him as a young man, all bright-eyed and square-jawed, dressed in pinstripes and hitting majestic home runs alongside the likes of Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, Johnny Blanchard and Hank Bauer.

But almost as soon as that image came upon me it faded, replaced by a much clearer one in which a smallish man with a high-pitched, weathered and delightfully raspy voice was seated at the head a virtual sea of blue-haired ladies and shrinking, terribly balding men – every one of them leaning forward and straining to hear the next words out of his mouth – smiling and announcing with a wonderful mix of warmth, pride and authority, “B...Eight.”

Baseball will go on without Brandon Inge. And it will most certainly go on without Moose Skowron. Honesty compels me to admit, it needs them no more than it needs you or me.

Baseball will go on without Brandon Inge. And it will most certainly go on without Moose Skowron. Honesty compels me to admit, it needs them no more than it needs you or me.

But make no mistake; the game, the Patio – and in the case of Moose, the world as a whole – will seem a slightly colder place without them. And I will miss them both.