In the spring of 1963, WNYS was a six-month old ABC affiliate in Syracuse, New York with a problem. Thanks in part to a powerful state-of-the-art tower on a hill overlooking Pompey, just south of town, the station had signal to spare. In fact, its all-new transmission not only blanketed much of the thick cluster of homes in and around Central New York, it bled up and down the Finger Lakes area, picking up dozens of small, signal-deprived, predominantly rural towns to the south and west of Syracuse in the process.

In the spring of 1963, WNYS was a six-month old ABC affiliate in Syracuse, New York with a problem. Thanks in part to a powerful state-of-the-art tower on a hill overlooking Pompey, just south of town, the station had signal to spare. In fact, its all-new transmission not only blanketed much of the thick cluster of homes in and around Central New York, it bled up and down the Finger Lakes area, picking up dozens of small, signal-deprived, predominantly rural towns to the south and west of Syracuse in the process.

What the new station didn't have was programming.

Not only was the upstart TV network ABC lacking much in the way of network-delivered content -- and, indeed, it did not yet feature a national news broadcast -- but the local station's new ownership had virtually nothing in the way of local programming, which many Syracuse viewers still flocked to, if for no other reason than they seemed to see something of themselves (and their neighbors) in it.

So that spring WNYS put into production a handful of locally produced TV shows, including a surprisingly well-done kids program called Ladybug's Garden and a Saturday late-night anthology series hosted by a Dracula-style character someone at the station decided to call "Baron Daemon".

So that spring WNYS put into production a handful of locally produced TV shows, including a surprisingly well-done kids program called Ladybug's Garden and a Saturday late-night anthology series hosted by a Dracula-style character someone at the station decided to call "Baron Daemon".

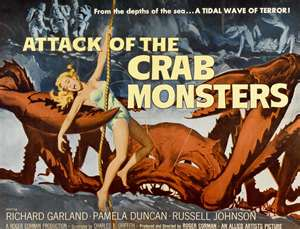

The horror series was built around WNYS' recent acquisition of a package of syndicated films that included some American International B-level horror flicks like Roger Corman's Attack of the Crab Monster, and featured intros and interstitial wrap-around clips hosted by Daemon (pronounced day-MOAN).

To finance its new horror series, WNYS sold an exclusive sponsorship to Frank's Pizza, a tiny pizzeria in the largely Italian neighborhood of Eastwood, which for years was owned and operated by Frank Sardino, whose brother, Tom, happened to be the Chief of Police of Syracuse.

To finance its new horror series, WNYS sold an exclusive sponsorship to Frank's Pizza, a tiny pizzeria in the largely Italian neighborhood of Eastwood, which for years was owned and operated by Frank Sardino, whose brother, Tom, happened to be the Chief of Police of Syracuse.

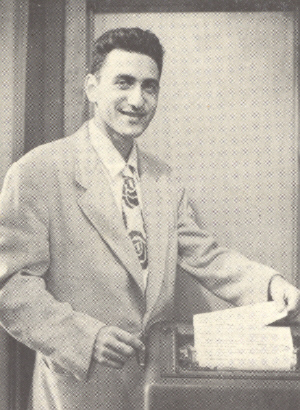

To play Daemon, the station then selected one of its staff announcers, 23-year old Mike Price, a local kid with a deep, resonant voice from Onondaga Valley High School. Price had been one of the station's last hires before it launched and he had come on board just days before WNYS signed on for the first time on September 9, 1962.

And what Price's Baron Daemon brought to the table ended up being more about youthful energy and broad, slapstick comedy than about authentic, organ-dripping and -- god forbid -- chill-inducing gothic horror.

As a result, the series -- complete with its cheesy drive-in titles littered with giant bugs, killer crustaceans and glowing spaceships -- was not just campy and carefree, it was downright fun.

Before they knew it, WNYS had their first hit on their hands, especially among Syracuse-area teenagers and their kid brothers and sisters. In fact, Baron Daemon's Saturday night horror series became so popular that in a matter of weeks Sardino found himself having to install three extra phone lines in his tiny pizza shop just to keep up with demand, and got swamped each week until the show went off the air at some point early Sunday morning.

Price, of course, loved it. He had gone to Syracuse University for a year, and even made the freshman football team, where he got to scrimmage almost daily against the 1959 National Champions and their Heisman Trophy winner, Ernie Davis. But he realized quickly that he wasn't really much of a student, or for that matter much of a football player, so he packed his bags, moved to New York City, and enrolled at something called the New York School of Broadcasting, where he earned not so much a diploma, as a certificate.

Price, of course, loved it. He had gone to Syracuse University for a year, and even made the freshman football team, where he got to scrimmage almost daily against the 1959 National Champions and their Heisman Trophy winner, Ernie Davis. But he realized quickly that he wasn't really much of a student, or for that matter much of a football player, so he packed his bags, moved to New York City, and enrolled at something called the New York School of Broadcasting, where he earned not so much a diploma, as a certificate.

But by the time he returned to his hometown, broadcast certificate in hand, he turned out to be the right guy, in the right place, at exactly the right time. So when WNYS hired him to read promos and some ads live and on-air, as well as to host a daily morning, trivia-based movie show, he dove in head-first and would, indeed, do just about anything the station asked of him.

In the spring of 1963, Price's never-say-never attitude, coupled with the fact that in L.A. a would-be actor named Bobby "Boris" Pickett had just a few months prior topped the pop charts with a runaway novelty hit called the Monster Mash, prompted someone in the WNYS publicity department to call another Syracuse local, Mike Riposo, who qualified as something of a genius when it came to audio tape and recorded sound.

In the spring of 1963, Price's never-say-never attitude, coupled with the fact that in L.A. a would-be actor named Bobby "Boris" Pickett had just a few months prior topped the pop charts with a runaway novelty hit called the Monster Mash, prompted someone in the WNYS publicity department to call another Syracuse local, Mike Riposo, who qualified as something of a genius when it came to audio tape and recorded sound.

Riposo for years had owned and operated a tremendously successful recording studio on the 10th floor of the old Onondaga Hotel in downtown Syracuse, and for almost as many years wrote and/or recorded countless jingles that shops large and small throughout Syracuse used to promote themselves on local radio and TV.

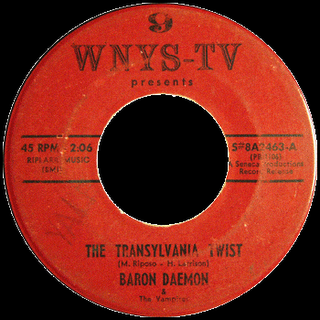

What the WNYS person on the phone wanted to know was, could Riposo write and record a pop-flavored jingle -- a la the Monster Mash -- for the station's first-ever breakout star, Baron Daemon? Riposo, a soft-spoken, bookish and highly disciplined craftsman who was never one to turn down work -- or for that matter, run from a challenge -- said sure, he could do that. And that's exactly what he set out to do in the spring of 1963.

This part of the story gets a little sketchy, because although Riposo composed the original music, the lyrics were actually penned by a roundish Irish wag named Hovey Larrison. Because Larrison was an ad man, as well as a successful copywriter in Syracuse, it is thought that possibly he was working with the agency that represented WNYS at the time Riposo was contracted, or maybe Riposo simply knew him and asked for help with the lyrics.

What's more, it is not sure if the name of the proposed Baron Daemon song was suggested by the WNYS publicity department at the time of the call to Riposo, or if Larrison took it upon himself to title it, based on a line in Pickett's original Monster Mash. ("Whatever happened to my Transylvania Twist?")

Whatever the case, the simple fact remains that the songwriting credit on the pop tune they eventually developed -- the Transylvania Twist -- reads to this day, "M. Riposo and H. Larrison".

Having composed the original melody, Riposo then made the first of two fortunate phone calls.

Having composed the original melody, Riposo then made the first of two fortunate phone calls.

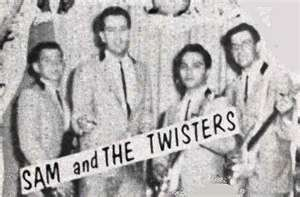

He first called Sam Amato, lead guitar player of the first Syracuse rock band to ever get regular airplay, a group called Sam and the Twisters. Earlier that year, Amato and band-mate Jan Fetterly, at the urging of their manager, "Dandy" Dan Leonard (a former classmate of actor Tony Curtis and rock impresario from Brooklyn who doubled as station manager of local Top 40 station WNDR), had re-tooled a nursery rhyme once popularized by Burl Ives, Fooba Wooba John, as an uptempo, danceable rock song, complete with a twangy surf-style guitar.

Sam and the Twisters' re-imagined version of Fooba Wooba John, which was recorded by Riposo in the winter of 1962, was a huge hit in its twist-crazy hometown of Syracuse and was still being played on both WNDR and its rival, WOLF, even as Riposo spoke to Amato.

Riposo said he'd like to hire Sam and the Twisters to record two songs he'd just written for Daemon and the publicity department at WNYS. He said he could only pay them a few hundred bucks, but that it wouldn't really be a long gig, in that they were only going to record two songs, one of which was an instrumental and would serve as a throwaway B side. Plus, they wouldn't have to sing a note.

He also said he'd send Amato and Fetterly the sheet music to both songs so that Sam and the Twisters could rehearse, should they choose, before the gig. They told him don't worry about it.

Riposo then placed a call to someone he knew at a competing television station. He remembered loving the jazzy vocal stylings of Jeanne, Norma and little Sandy Bigtree -- three young, incredibly talented singing siblings who performed under the name, the Bigtree Sisters -- on Jim Deline's Saturday morning variety show on WSYR, the NBC affiliate, which broadcast out of the Kemper Building, just a block or so south of the public library. Riposo thought the girls would be perfect to help carry the melody of his Transylvania Twist, particularly because at the end of the day, Daemon's alter-ego Price was neither a singer, nor an actor.

Riposo then placed a call to someone he knew at a competing television station. He remembered loving the jazzy vocal stylings of Jeanne, Norma and little Sandy Bigtree -- three young, incredibly talented singing siblings who performed under the name, the Bigtree Sisters -- on Jim Deline's Saturday morning variety show on WSYR, the NBC affiliate, which broadcast out of the Kemper Building, just a block or so south of the public library. Riposo thought the girls would be perfect to help carry the melody of his Transylvania Twist, particularly because at the end of the day, Daemon's alter-ego Price was neither a singer, nor an actor.

The problem was the girls, Mohawk natives by birth, had never sung rock and roll before in their lives. They were big-band lovers, show tune loyalists and jazz aficionados. And they saw themselves, not so much as a Syracuse version of the Crystals or Ronettes, but as a latter-day version of the Andrews Sisters. What's more, they rarely strayed from the standards and the Great American Songbook, and rarely sang contemporary pop tunes.

That would not be a problem, Riposo told the girls' mother, who lived with two of the three sisters in the family home on Midland Ave on Syracuse's south side -- Jeanne had since moved to New York and would have to return to Syracuse for the gig -- he'd give them all the instruction they'd need the night they laid the side down.

Like Sam and the Twisters, Mary Bigtree was told her daughters would be paid a couple hundred bucks for their background singing on the Transylvania Twist. The B side, he assured her, would not even require their services.

As they rehearsed for the session just before laying the track down, one thing became evident before Mike Riposo even turned on his tape machine; the song as written was a little rough around the edges. Riposo, for all his talents, was still not a rock composer. He was a commercial jingle writer. And the Transylvania Twist, at least in the eyes of Amato, Fetterly and the other Twisters, should not be a jingle, but a straight-forward rock song; in fact, a real honest-to-god twist song that kids would want to get up and dance to.

As they rehearsed for the session just before laying the track down, one thing became evident before Mike Riposo even turned on his tape machine; the song as written was a little rough around the edges. Riposo, for all his talents, was still not a rock composer. He was a commercial jingle writer. And the Transylvania Twist, at least in the eyes of Amato, Fetterly and the other Twisters, should not be a jingle, but a straight-forward rock song; in fact, a real honest-to-god twist song that kids would want to get up and dance to.

But one of Riposo's particular areas of genius was his uncanny ability to let talent do what they do best, be it singing, talking, announcing or playing, and then to record it and clean it up for public consumption.

That's clearly what happened here.

During the first two rehearsals, the melody line as played by the Twisters became less and less like the melody line originally composed by Riposo, and more and more akin to their local hit Fooba, Wooba John, which Amato and Fetterly had penned just months earlier.

Riposo didn't mind at all. He knew the band was onto something. And he let them go with it.

When they finally ran through the song a couple of times as tweaked by the band, Riposo knew they were getting close. But now the problem was Price. Normally a high-energy guy who could fall in and out of character at the drop of a hat, this particular night Baron Daemon was, at least in Riposo's opinion, somewhat flat and methodical during the first few takes.

Riposo knew that what he had was already good. But he knew Price could do better. What's more, the producer/sound engineer was almost obssessively particular, especially when he heard something that could become great with just a little extra oomph from the talent. He tried coaxing the WNYS staff announcer to ratchet up his energy a touch.

At this point, fact and fantasy once again merge, and depending upon who you talk to, Price was either in full costume, or not. He had either nailed the song on the first few takes, or he hadn't. And he either took a break to collect himself and summon up the irrepressible spirit of the Baron, or he didn't.

At this point, fact and fantasy once again merge, and depending upon who you talk to, Price was either in full costume, or not. He had either nailed the song on the first few takes, or he hadn't. And he either took a break to collect himself and summon up the irrepressible spirit of the Baron, or he didn't.

Amato told an interviewer years ago that he remembers clearly Price coming in full costume, including makeup, for the session, and that even heard that when the elevator operator at the Onondaga refused him entry because of the way he was dressed, Price found himself forced to walk up ten flights of stairs.

Price in a recent interview said, au contraire, he was never in full costume and did indeed take the elevator for the session. He also recalled the session being largely uneventful, given that the first two takes of the song were perfectly fine.

For her part, Sandy Bigtree, who was all of 12 at the time, remembered a hybrid of the two versions. She said that she didn't recall Price being in full costume, but she did feel some level of tension in the studio after the first two takes seemed to drag and lacked energy. But then she said she saw Price leave the studio and soon heard him pacing up and down the hall of the old hotel. She said she was wondering what was going on when all of a sudden, through the closed door, she heard Baron Daemon's demonic laugh once. Then twice. Then finally a third time.

When he finally returned a few moments later, Price had a fire in his eyes, and the unmistakable look, feel and carriage of the Baron. He strode straight to the mic and music stand at the center of the studio, his mouth wearing a devilish smile and his eyes glaring straight ahead.

The Bigtree Sisters, meanwhile, who had been working out their harmonies alone in the corner, quickly gathered around the suspended microphone to the right of the sound room, while little Sandy stepped up on the box that put her at roughly the same height as her older sisters, Norma and Jeanne.

And Sam and the Twisters, who had been just hanging out making small talk, quickly put out their cigarettes, grabbed their instruments, and assumed their positions.

And Sam and the Twisters, who had been just hanging out making small talk, quickly put out their cigarettes, grabbed their instruments, and assumed their positions.

"Let's do this, Mike," said Price in the Baron's voice to the sound man, who'd been seated behind the glass.

As soon as Riposo hit the record button and counted down his thrown-together group of musicians, something almost magical came over them. Every last person there that night could feel it. Sam and the Twisters were suddenly attacking the song they had, indeed, helped write, and had been, in essence, playing for months.

The Bigtree Sisters, now so comfortable with their parts and the lyrics that they got rid of the music stand in front of them, were now singing straight from their hearts, their eyes often closed as they let the music take them.

And Price, unlike the two earlier takes, simply became the Baron; snapping his consonants, twisting like a school kid in his imaginary cape, and more than anything else, accentuating key moments in the song's chorus with a long, extended diabolical laugh.

And Price, unlike the two earlier takes, simply became the Baron; snapping his consonants, twisting like a school kid in his imaginary cape, and more than anything else, accentuating key moments in the song's chorus with a long, extended diabolical laugh.

At 2:07, Riposo finally faded the kinetic take into nothingness. He gave his musicians all a moment to collect themselves, even as the energy they'd just mustered continued to crackle all around them in the studio. Then, as was his style when he really liked a particular take, Riposo didn't jump up and down. He didn't smile. He didn't even say, "Good job." He simply leaned toward the mic behind the board, pushed the button for the intercom, and said in his own understated, matter-of-fact way, "Why don't you give me a safety, just to be sure?"

For those who knew him, when Mike Riposo asked for a safety he may well just have said, "Congratulations. You'll never do it any better than that."

While no one in the Syracuse of the day would have contended that Pickett's Monster Mash was not a great song (I, for one, bought a second copy after my first started to wear out), most of those same people would have also contended -- indeed, many still do to this day -- that the Transylvania Twist was the better rock and roll record. And, frankly, by a long shot.

There were some obvious differences, of course. Pickett was largely channeling Boris Karloff, while Price was lampooning Bela Lugosi.

There were some obvious differences, of course. Pickett was largely channeling Boris Karloff, while Price was lampooning Bela Lugosi.

The Monster Mash was a dance song designed around a dance craze at the time, the Mashed Potato. The Transylvania Twist was a record built around a somewhat older dance craze, the Twist.

And clearly the Monster Mash was a national phenomenon, while the Transylvania Twist ended up being little more than a one-in-a-million shot by a bunch of local kids.

But at the end of the day, the Transylvania Twist had something the Monster Mash never had, and never would have. It was real.

Hearing the Monster Mash now, and knowing its back story, its really hard to look past the professionalism at play, knowing its writer, producer and performers always seemed to have one eye on their work and one eye on the cash till.

The Transylvania Twist, on the other hand, seems authentic, even to this day. It was as though those nine people -- eight musicians and an engineer -- came together for one shining moment and in that one moment captured the very essence of rock and roll -- or at least rock and roll's still-innocent youth.

The recording is grainy and a little muddy. It is echoed, in large part because the producer was trying to simulate a cave. And it lasts barely two minutes.

But it crackles with energy and raw power. It's as though, if Monster Mash were some product of, say, Phil Spector or Quincy Jones and a team of All Star sidemen, the Transylvania Twist, even to this day, seems like an unvarnished and entirely raw garage-band song, dreamed up and played by a bunch of kids trying not to drown in a bubbling cauldron of teenage angst, musical expression and arcing chromosomes.

Listen to the powerful drumming of Jan Fetterly. It's as though he's trying to machine gun some unseen enemy and it seems at times he could care less about collateral damage.

Listen to Amato's stinging, slightly muted lead guitar. He had always admired the Ventures' Bob Bogle, but on the Transylvania Twist he seems to have morphed into Bogle's evil twin, playing a West Coast surf guitar with a kind of ferocity rarely heard on a simple dance song, much less a promotional jingle.

And to hear the Bigtree Sisters, you can't help but realize what great actresses all three could have become. Because for those two minutes, they are no longer just three straight-laced Mohawk girls from Syracuse's south side. They're a true rock and roll chorus. For at least the running time of that song, they quite literally transform themselves into a trio of not-so-innocent girls from the other side of the tracks; girls who believe, until life tells them otherwise, that happiness is all about stealing away to pop gum, smoke cigarettes, sport bee-hive hairdos, and when they can, sneak sips and kisses from whatever they can get their hands on.

But more than anything else, listen to Mike Price.

But more than anything else, listen to Mike Price.

Listen to his energy and his echoed, demonic laugh. He's flat-out selling Baron Daemon like he never had before or, frankly, never would again.

Riposo was smart not to over-expose his singing limitations on the record, and, indeed, he let the Bigtree Sisters sing the first half of the second and third verses. But Price remains the core of the song and it is his vocal performance and his incredible vocal energy that helped elevate the Transylvania Twist into something more than just a throwaway promo.

That's why Baron Daemon's lone hit single became a local smash hit and the largest-selling local record in Syracuse history.

That's why every Halloween it reemerges from its coffin to remind Central New Yorkers everywhere, even the young ones, what radio was like before processed, filtered, and homogenized national feeds.

But more than anything, that's why people old enough to remember the golden age of CNY radio still believe where it matters most -- in their still-young, still-beating and still-dancing hearts -- that one of the great garage-band classics of all time, Baron Daemon's Transylvania Twist, still rises from the dead once a year to kick the Monster Mash's ass.

Transylvania Twist Odds & Ends: