It was a rainy afternoon in October. I had just driven up to Detroit from Toledo in my stylish Chevy Lumina, compliments of my dear friends at Hertz, and still had a few hours to kill before my flight back east.

It was a rainy afternoon in October. I had just driven up to Detroit from Toledo in my stylish Chevy Lumina, compliments of my dear friends at Hertz, and still had a few hours to kill before my flight back east.

It was then that I made one of the better decisions of my life.

I pulled over to a gas station and asked directions to 2648 West Grand. After giving me a look that said "Why the hell would someone like you driving something like that want to go anywhere near West Grand for?" the guy behind the counter just pointed out the window and said. "Just take this a few miles that way. It'll cross West Grand. I think 2648 will be to your right."

With that, this gone-to-seed, middle-aged white boy got back into his sporty, mid-sized Chevy and headed off toward a place where dreams and music once rolled off a Detroit assembly line like so many Fords, Pontiacs and Chryslers.

I knew the address because as a music geek, it's part of my job to know such things.

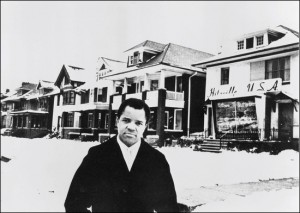

But for the non-geeks among you, 2648 West Grand Boulevard was the former site of Motown Records, a small brick two-story house in the middle of a residential section of Detroit; a house that starting in 1959 served as a studio, office, and living quarters for both the label and its founder, Berry Gordy.

Gordy would eventually paint the place white with powder blue trim, buy the brick house next door, connect the two, and christen the two in tandem, Hitsville, U.S.A.

Gordy would eventually paint the place white with powder blue trim, buy the brick house next door, connect the two, and christen the two in tandem, Hitsville, U.S.A.

(And one might argue that, even then, the name simultaneously qualified as both boldly ambitious and something of an understatement.)

But by mid-90's, and by the time I traveled there, Hitsville had become a shadow of its former self, and the neighborhood Motown Records once called home something less than that.

The company had long since pulled up stakes and moved to sunny L.A., long since been sold by its founder to a team of merchant music-makers, and long since been swallowed whole by one corporate behemoth after another, until the original brand and all it once stood for seemed little more than a memory.

When I was there, Hitsville U.S.A. was just an unassuming little shrine to a otherwise magical time in pop history; a somewhat quirky roadside attraction in a slowly decaying part of a rapidly decaying town, refurbished to a degree and opened to a public that, given the fact I was the only paying customer for the better part of two hours, apparently could have cared less.

When I was there, Hitsville U.S.A. was just an unassuming little shrine to a otherwise magical time in pop history; a somewhat quirky roadside attraction in a slowly decaying part of a rapidly decaying town, refurbished to a degree and opened to a public that, given the fact I was the only paying customer for the better part of two hours, apparently could have cared less.

In fairness, 15 years ago when I was there, many of the artifacts that today constitute the bulk of the Motown Museum experience were AWOL; on loan to the all-new Henry Ford Museum just down the road; swapped out on a temporary basis in exchange for what amounted to a life-saving infusion of cash.

Bad luck for your garden-variety fan of 60's soul music. But a stroke of incredible good fortune for a Motown geek like yours truly.

Because that day I could have cared less about seeing some sequins dress worn by Diana Ross at the Apollo, or Martha Reeve's first contract, or even Marvin Gaye's blue suede shoes. I wanted to see the building, the studio, the place where all that incredible music got made.

I wanted to see Hitsville, the best-run factory in the greatest little factory town the world had ever known.

I wanted to see Hitsville, the best-run factory in the greatest little factory town the world had ever known.

After spending roughly five minutes in the lobby resisting the overtures of a young African-American staffer in his late teens or early twenties, wearing thick black glasses and a shirt and tie, I finally acquiesced. I'd let him be my guide and give me the full-blown Motown Museum tour, complete with narrative.

(As it turned out, yet another in a long line of very fortunate decisions for me that day.)

The kid was great. Better than great, actually. And the story -- or should I say stories -- he told me were even better still.

He showed me a display with all the album covers from the label's early days, when Gordy refused to let his art director use photos of the artists for fear the LPs would sit in record stores down South, unsold and un-played.

He showed me a display with all the album covers from the label's early days, when Gordy refused to let his art director use photos of the artists for fear the LPs would sit in record stores down South, unsold and un-played.

He took me upstairs and let me walk through Gordy's tiny apartment, which had been restored to its original vintage, complete with its original sofa, original bedroom suite and original kitchen table.

The kid then let me sit at the table, on which sat a box of newly minted 45s, a stack of envelopes and an old dog-eared Cashbox magazine with the address of every Top 40 station in the country. It was at that very table that Gordy used to send out his new singles one-by-one to key DJs and music directors from Maine to California, along with a hand-written note of thanks for playing the record.

And while we were upstairs, the kid pulled down a trap door which led to the attic, and let me climb up the folding stairs to take a look. There amid the rafters I saw in an otherwise empty attic a few pieces of plywood, two big speakers and a mic stand holding a '60s-vintage microphone.

"You see that?" the kid asked me. "Do you know what that's for?"

I told him I had no idea.

He said that one day one of the Motown engineers decided to run a feed out of the recording studio up to the attic, so the music would come out the two speakers and get picked up by the microphone before being sent back down to the mixing board in the control room.

"You know that rich, full sound, almost like an echo, you hear on those real old Motown records?" he asked me. "That's how they got it. Cost 'em a few hundred dollars."

"You know that rich, full sound, almost like an echo, you hear on those real old Motown records?" he asked me. "That's how they got it. Cost 'em a few hundred dollars."

He then added, "They spent over a million dollars trying to get the same sound when they moved everything out to L.A. But as hard as they tried, and as much money as they spent, never could do it though."

Then on our way back down to the first floor the kid told me the story of Berry Gordy's "star factory." He told me how Gordy took the assembly line principles he witnessed during his brief time as an autoworker and applied them to making music and pop stars.

He pointed to a door which led to the parking lot out behind the building. "You see that door there? Mr. Gordy would take a young person with talent in through the back door, just like Ford or GM might take the raw materials to build a car, then he'd take the talent, clean it, mold it and shape it. And when he was done, he'd send that young person out the front door all shiny and polished and ready to be a star."

Indeed, my young guide then pointed across West Grand to an old house badly in need of a paint job. He told me that house used to be Ms. Powell's Finishing School. That, he said, was where a woman named Maxine Powell, a former actress and model who had trained under John Powers in Chicago, taught all the young Motown artists -- many of whom she would later claim were "rude and crude" -- how to walk, talk and interact in white society, especially when in the presence of the residents of two homes in particular: "the White House and Buckingham Palace."

Indeed, my young guide then pointed across West Grand to an old house badly in need of a paint job. He told me that house used to be Ms. Powell's Finishing School. That, he said, was where a woman named Maxine Powell, a former actress and model who had trained under John Powers in Chicago, taught all the young Motown artists -- many of whom she would later claim were "rude and crude" -- how to walk, talk and interact in white society, especially when in the presence of the residents of two homes in particular: "the White House and Buckingham Palace."

He then told me how, of all the performers, the already suave and sophisticated Marvin Gaye resisted Powell's efforts the most, believing he didn't need any further polishing. Which may have been true to some degree.

He then told me how, of all the performers, the already suave and sophisticated Marvin Gaye resisted Powell's efforts the most, believing he didn't need any further polishing. Which may have been true to some degree.

But Ms. Powell eventually won the budding star over by telling him he sang with his eyes closed, which robbed him of two of his greatest assets as a performer. She said she'd teach him Gaye to use not only his voice but his eyes to seduce his audience.

She also told him that, as handsome as he was, he had to learn to use his body to his advantage, and not just on stage, but when entering a room or simply walking down the street.

From that point forward, Marvin Gaye listened to almost everything Maxine Powell told him.

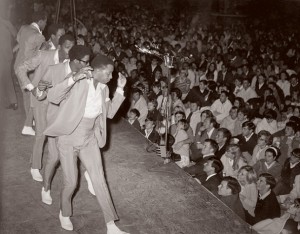

I learned too about Cholly Atkins, Motown's in-house choreographer and another long-forgotten member of a Motown department that back in the day Gordy euphemistically called Artist Development, a department which proved to be a vital cog in the hit-making machinery of Motown Records, and one which, until 1969, was run with a firm hand by Maxine Powell.

The kid explained to me that it was Atkins who almost single-handedly invented the kind of on-stage moves now synonymous with legendary vocal groups like the Temptations, Miracles, Four Tops, and perhaps above all, the Pips; moves which, like the Supremes' hands-out/palms-forward gesture in "Stop, In the Name of Love," are now so iconic they've almost become parodies of themselves.

The kid explained to me that it was Atkins who almost single-handedly invented the kind of on-stage moves now synonymous with legendary vocal groups like the Temptations, Miracles, Four Tops, and perhaps above all, the Pips; moves which, like the Supremes' hands-out/palms-forward gesture in "Stop, In the Name of Love," are now so iconic they've almost become parodies of themselves.

But all this history was just an appetizer for what I really came to see, something which turned out to be the very last stop on my hour-long tour of Hitsville, U.S.A.

Studio A.

My guide walked down the four steps into a tiny -- and I do mean tiny -- slightly recessed room covered from ceiling to floor with various combinations of acoustic tiles, pieces of pegboard and aging plaster, all of it time-worn and smoke-stained, with one large, incredibly thick window to a slightly elevated control room.

My guide walked down the four steps into a tiny -- and I do mean tiny -- slightly recessed room covered from ceiling to floor with various combinations of acoustic tiles, pieces of pegboard and aging plaster, all of it time-worn and smoke-stained, with one large, incredibly thick window to a slightly elevated control room.

And in that tiny, sunken room I saw laid out perfectly, almost as though a recording session had either just ended or was about to start, a vintage Hammond B3 organ and baby grand piano to my left, three music stands with vintage, old-school microphones suspended from booms dead ahead, and a shiny but well-worn drum set to the right near the back, along with an old set of vibes along one wall, a hulking analog tube amp along another, a couple of folding chairs upon which rested an electric guitar and a Fender bass, not to mention, literally, dozens of headsets, sound cables and other tools of the trade hanging from hooks attached to various pieces of the pegboard.

And in that tiny, sunken room I saw laid out perfectly, almost as though a recording session had either just ended or was about to start, a vintage Hammond B3 organ and baby grand piano to my left, three music stands with vintage, old-school microphones suspended from booms dead ahead, and a shiny but well-worn drum set to the right near the back, along with an old set of vibes along one wall, a hulking analog tube amp along another, a couple of folding chairs upon which rested an electric guitar and a Fender bass, not to mention, literally, dozens of headsets, sound cables and other tools of the trade hanging from hooks attached to various pieces of the pegboard.

"Wow," I said as I tried reconcile the smallness of the room with its lofty place in musical history, "This is where they made all that music?"

I must have been standing on that top step for the better part of a minute, because my guide eventually said to me, "It's OK, sir. You can come on in."

I told him, "No, you don't understand. This...this place is like a cathedral to me." I then chuckled and said, "I'm just standing here trying to decide whether or not I should genuflect first."

I told him, "No, you don't understand. This...this place is like a cathedral to me." I then chuckled and said, "I'm just standing here trying to decide whether or not I should genuflect first."

I eventually did go in, of course, and eventually was regaled with a few other tales about Motown's early days, including the one about the first time the boss heard 8-year old Stevie Wonder play that same baby grand piano, and how Gordy stuck his head out of the control room door like a prairie dog almost as soon as Wonder's hands hit the keys.

But I'll tell you this: none of what I've related to this point ended up being my ultimate takeaway from my tour of the Motown Museum that cold and rainy day.

All of it was pretty cool, I'll grant you. And all of it was well worth the trip.

But the one thing that still remains frozen in my consciousness, and the thing that now comes to mind whenever I hear the name Motown is this: as we were leaving and walking past the control room, my young guide stopped and asked me, "Remember, how I said Mr. Gordy treated this place like a factory, and how he would take raw materials in the back door and send polished stars out the front?"

But the one thing that still remains frozen in my consciousness, and the thing that now comes to mind whenever I hear the name Motown is this: as we were leaving and walking past the control room, my young guide stopped and asked me, "Remember, how I said Mr. Gordy treated this place like a factory, and how he would take raw materials in the back door and send polished stars out the front?"

"Sure," I told him.

"Well, there's more to it than that," he said, and proceeded to tell me that at the peak of Motown's success, Gordy used to run his little music factory on West Grand around the clock, seven days a week, 365 days a year, in "shifts," much like Ford, Chrysler and GM ran three shifts a day to keep up with demand.

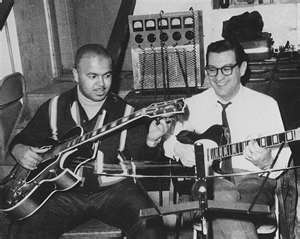

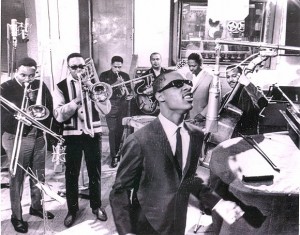

At Motown, the kid told me, Gordy assigned each "shift" a producer and an engineer, who would then work as a team for eight hours straight recording songs that the label's various writing teams had written for its various artists. "They recorded in Studio A non-stop for almost 13 years, three shifts a day," the kid told me.

At Motown, the kid told me, Gordy assigned each "shift" a producer and an engineer, who would then work as a team for eight hours straight recording songs that the label's various writing teams had written for its various artists. "They recorded in Studio A non-stop for almost 13 years, three shifts a day," the kid told me.

He then pointed to two spots on the floor of the control room just to the right of the two chairs where those producers and engineers sat while recording those non-stop sessions. As he continued to point he simply turned toward me and said, "Look."

I looked in the direction of where his finger was pointing and stared at what apparently he was trying to point out. It was two dark brown spots on an otherwise neutral-colored tile floor. I stared for a while, a blank expression on my face, not entirely sure what the point was.

But finally it sank in. Finally I got it. And finally I came to realize exactly what my young guide was trying to show me.

He was pointing out some trace evidence of musical history.

Realizing it, I then slowly raised my head, turned to the kid, and with a little half-grin said, "Now that's cool."

Words weren't necessary, and the kid knew it. He knew he didn't need to explain to a music geek like me what those two dark brown spots were.

Words weren't necessary, and the kid knew it. He knew he didn't need to explain to a music geek like me what those two dark brown spots were.

Anyone who'd ever been swept away by the sheer force and rhythmic power of a song like "Nowhere to Run," "Ain't that Peculiar," "Baby I Need Your Lovin'," "Nothing's Too Good For My Baby" or "Dancin' in the Street", or who had been overcome by the driving energy of the Funk Brothers as they sent yet another Motown single soaring into the musical stratosphere knew exactly what those two spots on the floor were.

After 13 year's worth of non-stop recording, three shifts a day, seven days a week, 52 weeks a year, at some point the ugly, coffee-stained linoleum on floor of the control room finally gave in. And at those two specific spots on the floor, each separate and distinct -- one under the right foot of the producer, the other under the right foot of the engineer -- the linoleum had been worn away to -- and I mean this literally -- nothing.

Nothing.

All those sessions, all that rhythm, and all that infectious soul music had triggered wave after wave of relentless toe-tapping to the point that it eventually eroded the tile straight down to the hardwood floor beneath it. And all that was left of the linoleum in those two spots beneath the Studio A console were two holes, each sand-paper smooth and each about three inches long.

Two small holes in a crumby tile floor. That was my takeaway -- my absolutely perfect moment -- from that long-ago trip to Hitsville.

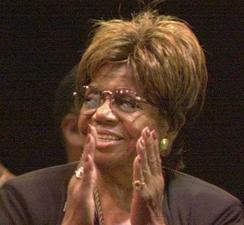

And that's why when I heard this past week about the death of Berry Gordy's big sister, Esther Gordy Edwards at the age of 91, and when I read in the New York Times about the role she played in preserving so much of Motown's history, I felt compelled to dust off my memories and commit them to words.

And that's why when I heard this past week about the death of Berry Gordy's big sister, Esther Gordy Edwards at the age of 91, and when I read in the New York Times about the role she played in preserving so much of Motown's history, I felt compelled to dust off my memories and commit them to words.

You see, without Ms. Gordy Edwards, today there might not be a Hitsville, U.S.A. -- at least not the Hitsville I visited that rainy afternoon, or the Hitsville that now stands as a shrine to Motown's long-lost days of innocence and its humble roots.

Without Esther Gordy Edwards, Motown might exist today only as an endless string of box sets, digital downloads, photos, books and oral histories; derivative artifacts of what was once a very real place and a very real time.

But of all the people in the company in a position to do so, it was only Esther Gordy who refused to part with those hopelessly outdated, and seemingly useless buildings on West Grand Blvd.

But of all the people in the company in a position to do so, it was only Esther Gordy who refused to part with those hopelessly outdated, and seemingly useless buildings on West Grand Blvd.

It was only Esther Gordy who for years kept stored all that cheap, tacky furniture and who held on so dearly to all that outdated analog equipment, including Hitsville's beat up old Studio A console.

And only Esther Gordy who realized the historical significance of all those scraps of paper and all that "junk" that so many others in the company were so willing to toss to the curb as they bolted the Motor City for points west.

And finally, it was only Esther Gordy who decided to spend the money to transform her brother's crumbling old Hitsville complex into a musical touchstone and an historical oasis for others to enjoy for years to come.

In other words, of all the people in Motown, only Esther Gordy had the vision and the foresight to see a day when future generations would want to step back in time and experience the living, breathing history of a company that changed forever the face of music in America, a company she helped build, a company whose impact on 20th Century popular culture remains, even now, difficult if not impossible to calculate.

So while many will choose to remember the remarkable Esther Gordy Edwards as the "Mother of Motown," a whip-smart, buttoned-down lady with both a great head for business and an enduring sense of dignity, I'll choose to remember her in a slightly different way.

So while many will choose to remember the remarkable Esther Gordy Edwards as the "Mother of Motown," a whip-smart, buttoned-down lady with both a great head for business and an enduring sense of dignity, I'll choose to remember her in a slightly different way.

I'll remember her as a museum curator and a lover of history. Because Ms. Gordy Edwards proved to be a woman who knew the importance of preserving history, even as she was busy making it.

In fact, her little brother on the very day she died said in a statement, "Esther turned the so-called trash left behind after I sold the company into a phenomenal world-class monument."

That she did, Mr. Gordy

And that's why I consider your big sister an historian of the first order, and why I'm writing today in tribute to her and her amazing legacy.

Because 15 years ago your sister made possible one of the most profound musical experiences of my life.

And because at some point in her rich, full life -- like so many others would eventually do, and so many others would eventually realize -- Esther Gordy Edwards saw two little holes in an old linoleum floor and figured they weren't worth fixing.

And because at some point in her rich, full life -- like so many others would eventually do, and so many others would eventually realize -- Esther Gordy Edwards saw two little holes in an old linoleum floor and figured they weren't worth fixing.

But they were sure worth saving.