Nine down, one to go. And please forgive the delay between posts. It seems the higher up this list I go, the more difficult these narratives are to write. (Not because I don't have enough to say about each song, but because, in many cases, I have too much. The hard part, I guess, is determining what to leave out.)

Nine down, one to go. And please forgive the delay between posts. It seems the higher up this list I go, the more difficult these narratives are to write. (Not because I don't have enough to say about each song, but because, in many cases, I have too much. The hard part, I guess, is determining what to leave out.)

And for what it's worth, especially now we're at the home stretch, the final countdown, or whatever you want to call it, I do hope you'll take a moment to read even a handful of these narratives, if only to understand why that particular song made the list, and perhaps more important, why that song means as much as it does to me.

Thanks. And enjoy.

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 1

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 2

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 3

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 4

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 5

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 6

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 7

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 8

Desert Island Jukebox: Part 9

Desert Island Jukebox: Songs 26 thru 30

Desert Island Jukebox: Songs 21 thru 25

Desert Island Jukebox: Songs 16 thru 20

Desert Island Jukebox: Songs 11 thru 15

Desert Island Jukebox: Songs 6 thru 10

Desert Island Jukebox: Songs 1 thru 5

31. Yeh-Yeh

Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames

1965

It was called vocalese, the practice of layering lyrics atop bebop melodies, and prior to it most bebop jazz vocals were often just free-form scatted syllables. History’s most famous practitioners of the technique (and famous here is a relative term) were Lambert, Hendricks & Ross, three talented vocalists who became the Mod Squad of ‘50s jazz (“one white, one black and one blonde”). Prior to their coming together, Anne Ross had once put words to an existing bebop tune and came up with Twisted, a minor jazz hit for her that was subsequently covered, most notably, by Joni Mitchell and Bette Midler. Then one day, LH&R's Jon Hendricks took a little known bebop cut by Mongo Santamaria, added lyrics, the three went into the studio, recorded and released it, and Yeh-Yeh became a jazz hit (another relative term) in '63. But two years later when British R&B keyboardist Georgie Fame covered Yeh-Yeh, and did so with a decided rock ‘n roll bent, the resulting 45 not only became an unlikely sensation in England, it turned out to be the one and only time a little known jazz technique called vocalese would ever make the pop charts. It left its mark on my young mind, however, and I still can listen to this bold song now and feel it sounds as fresh and innovative today as it did when I first heard it on my little pocket Philco one hot afternoon nearly 50 summers ago.

32. If I Ruled the World

Tony Bennett

1965

Before he laid himself bare on MTV Unplugged and was rediscovered and deemed cool by a new generation of swingers, lounge lizards and hipsters, Tony Bennett was just another fading crooner trying like hell to keep a sputtering career alive. And me? I was a bartender a year or so out of college trying to hold adulthood at bay for as long as humanly possible. One night I stopped in the Hotel Syracuse to see a fellow worker. At the end of the bar, alone and clearly drinking with purpose, was a smallish man with a slightly cocked toupee. I said, “Oh my God, Tony Bennett!” He looked up and smiled. I told him my mother was a huge fan and loved his music, and how as a kid I could remember her running the vacuum, washing dishes, and dusting as she played his LPs at ear-splitting levels, singing all the while along with him. I told him my favorite song of his was this one, in part because it’s the one that made my mom stop what she was doing and listen to him go up and get its last note. “Moved her every time,” I told him as I raised my glass in his direction. The singer looked up, motioned to my friend to set me up again, and then peering into the mirror behind the row of amber bottles facing him said to no on in particular, except maybe the hollow reflection he found staring back at him, “Yeah kid, I gotta tell ya’. I’m real big with the mothers.”

33. And Suddenly

Cherry People

1968

These five D.C.-based hard rockers at one point did a full 180 and embraced, of all things, sunshine pop. But the Cherry People didn’t just embrace that delicious but short-lived micro-niche of pop music history; with this lilting little gem (that didn’t even manage to crack the Top 40) they helped define it. Because with this billowy bale of cotton candy, those recovering, one-time head bangers blessed my generation with one of the finest and purest examples of sunshine pop ever made. And while I have to admit this song had always been a guilty pleasure of mine, its impact on me turned out to be far greater than others of its ilk. Because as much as any other song, when I heard this single one day some 30 years after its release, it compelled me once and for all to embrace my inner nerd and begin freeing myself from others’ expectations, while focusing on all the things that bookish, squirrelly little voice inside me apparently been trying to tell me for years. "Stop worrying," I finally heard the voice say. "You're not that cool."

34. The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore

Walker Brothers

1966

There is so much to like about this song; its stunning, cascading Wall of Sound vibe and background vocals; lead singer Scott Walker’s powerful yet sleepy eyed croon; and the little known fact that it’s not an original at all, but a cover of a Frankie Valli misfire from the year prior. But the thing I like best is this. It is a 45 co-written, produced and arranged by an unknown giant named Bob Crewe, one of the most under-appreciated hit makers of all time. Because it was Crewe who wrote, produced and/or arranged hits as raucous and rockin’ as Devil With a Blue Dress/Good Golly Miss Molly, Sock it to Me, Baby and Jenny Take a Ride for Mitch Ryder and as gentle and melodic as Jean and Good Morning, Starshine for Oliver, not to mention the Tremolos’ Silence is Golden. It was Crewe who almost singlehandedly shaped the sound (and fortunes) of the Four Seasons, co-writing Rag Doll, Dawn, Sherry, and the incredible Walk Like a Man, and arranging many others, like the sublime, almost otherworldly, Candy Girl. It was Bob Crewe who released one of the signature instrumentals of the swingin’ ‘60s, Music to Watch Girls By, and who did the wonderfully atmospheric score to a film that's now the poster child for free love and space age cheesiness, "Barbarella." It was Crewe who wrote and produced Valli’s finest solo effort, Can’t Take My Eyes off of You, a song that has somehow managed to elbow its way into the Great American Songbook. And it was Bob Crewe who wrote two of the finest slices of American pop in the often vapid ‘70s, Valli’s terrific quasi-disco hit, Swearin’ to God and LaBelle’s stunning homage to New Orleans, working girls and pent up suburban desire, Lady Marmalade, one of the greatest pop records ever made.

35. California Sun

Rivieras

1964

Morris Levy was a gangster/music impresario who used mob money to start or finance major record labels, including Roulette, Sugar Hill, Kama Sutra and Buddah, launch regional record giant Strawberries, and open more than his share of music venues, the most storied of which was New York’s legendary, Birdland. But of all the things Levy (the inspiration for the character Hesh Rabkin in The Sopranos) did in his time to either launder mob money or put it in their pockets, none seemed any colder or less scrupulous than his habit of hiring poor songwriters, often uneducated black ones, paying them as little as $100 per song (along with its publishing rights), and then registering that song with BMI and/or ASCAP with himself as one of its composers. The practice made Levy millions in misdirected royalties and turned him into the “co-writer” of such pop classics as Why Do Fools Fall in Love, Peppermint Twist, My Boy Lollipop and this one. But that aside, the first time I ever heard punk, I listed to its pounding, almost hyperkinetic backbeat and thought immediately to myself, “California Sun.” That’s what this timeless little rocker remains for me; if not the world’s first punk rock song, then at least the world’s finest example of a musical sub-genre still awaiting its second entry; surf punk.

36. What Have They Done to the Rain?

Searchers

1965

What’s less than a minor hit? A mini hit? A micro hit? If so, let’s call this one a nano hit. But that doesn’t change the fact that this long-forgotten (if not little known) Malvina Reynolds folk tune/anti-nuclear protest song is as infectious as (choose a bacterial strain here). Reynolds, a second-generation activist and pacifist (her parents were Jewish immigrants who settled in San Francisco and spent years protesting and speaking out against World War I), ended up writing a number of songs that left their mark on pop culture. Her Little Boxes was a staple for Pete Seeger in concert and later became the theme of the Showtime series, “Weeds.” And Harry Belafonte’s version of her Turn Around, used by Kodak in a series of era-defining TV spots in the early ‘60s, turned out to be as emotionally wrenching (and memorable) a song ever licensed to Madison Ave. But of all the tunes Malvina Reynolds ever penned, for my money this little gem – or at least the Searchers’ ethereal and almost eerily undercooked version of it – remains in a class by itself.

37. Walk Like a Man

Four Seasons

1963

For years I used to lump this Bob Crewe/Bob Gaudio nugget in with those other terrific but largely dismissible early ‘60s tunes they wrote for the Four Seasons, like Dawn, Sherry, Rag Doll, Ronnie and Big Girls Don’t Cry. But years later – and I mean years later – while suffering through the pain of yet another gut wrenching breakup, I found myself driving all alone one night when this amazing song came on the radio. And as I drove through the dark stillness and listened, one line in it (and I mean that literally; one line) changed me in a way that was as profound as it was liberating. I’d never really heard it before; or at least not heard it the way I did that night. And you probably know which one it is. “No woman’s worth crawling on the earth…so walk like a man my son.” Oh, I promise you; I’ve had my heart broken since. But after really hearing Frankie Valli tell me for the first time that no woman’s worth crawling on the earth, never again would I let a broken heart get the better of me. And never again would a breakup ever feel like the end of the world.

38. Like to Get to Know You

Spanky and our Gang

1968

When we met we were working at the New York State Fair. She was 17. I was 23. Hell, back then people thought I was cradle robbing. But Susie and I fell in love and ended up sharing a great deal over the next two years. But in time I moved to Chicago, she went off to college, and the whole thing just sort of fizzled. But years later Susie and I crossed paths and became friends, something we remain to this day. And I remember once over coffee she told me that of all the songs she’d occasionally hear on the radio, none reminded her any more of me than this one. “I’m not sure you even know how much you loved that stupid little thing,” she told me. “You would always reach over to turn it up whenever it came on.” 'You know what? She was right. And I still love that stupid little thing.

39. Just Like Me

Paul Revere and the Raiders

1966

Take away those silly tricorn hats and Revolutionary War uniforms, Mark Lindsay’s teen idol dreaminess, and the fact these guys lost any semblance of street cred when they turned up as the house band for “Where the Action Is,” Dick Clark’s daily exercise in record promoting (in unlikely and often odd L.A. settings), and what you have left is a body of music that holds up remarkably well. And no song in the Raiders’ canon has any bigger balls than this one; a proto-punk rave that is every bit the equal of many of its more lionized garage contemporaries, like Louie, Louie, Wild Thing and 96 Tears.

40. Six O’Clock

Lovin’ Spoonful

1967

This one was little more than a fringe hit, and just like so many other Spoonful tunes, you either got Six O’Clock or you didn’t. But as a young man in his 20s who in his life had already loved deeply and lost, who was slowly learning to put the foibles of youth behind him, and who'd finally started to view women less as sexual conquests and more as potential life partners, I’m not sure I’ll never be able to explain the deep comfort and profound sense of clarity I found in a single line from this John Sebastian gem (a song I'd stumbled upon almost by accident when my parents gave me Hums of the Lovin’ Spoonful some ten years earlier). “And I could feel I could say what I want. That I could nudge her and call her my confidant.” Wow, I thought. All I ever wanted in a woman right there in a line of a song. Gotta be honest, it still gets me.

41. I Was Made to Love Her

Stevie Wonder

1967

How many Top 40 hits were co-written by a 16 year old kid and his mother? Well, here’s at least one; for my money one of the two greatest singles ever released by the “Little” version of Stevie Wonder (and maybe the grown up version too). But let’s forget that for a moment. Wanna have some real fun? At some point, Google “Who played bass on I Was Made to Love Her?” then sit back and start clicking, scrolling, digging and reading. You’ll end up being a fly-on-the-wall for one of the most colorful and hotly contested debates in Internet history. Was the bass player for this classic tune James Jamerson, the legendary Motown bassist who not only drank himself to an early grave, but who by the summer of ‘67 was well on his way? Or was it Carol Kaye, the equally legendary West Coast queen of the instrument who played on more Top 40 hits, storied Phil Spector, Quincy Jones and Brian Wilson sessions, commercial jingles, TV themes and movie soundtracks than the next three people combined? Either way, just do it. I promise you. You’ll have a blast.

42. The Lady Came from Baltimore

Bobby Darin

1967

After he emerged from his self-imposed retirement and two-year exercise in soul searching/soul cleansing – sans toupee and finger-popping swagger – Darin quietly went into the studio and began laying down a series of simple, unadorned and truly great renditions of songs by a number of the best young singer/songwriters of the day, including Bob Dylan (Blowin’ in the Wind), John Sebastian (Lovin’ You), Jagger & Richard (Backstreet Girl) and, especially, Tim Hardin (If I Were a Carpenter). But of all those folk (or at least folkish) songs Darin would do shortly before his death, this sketchy and enigmatic little half-told tale of forbidden love, class struggle, deceit and thievery – a Hardin tune subsequently covered by artists ranging from Johnny Cash and Joan Baez to Ricky Nelson and Scott Walker – turned out to be my favorite of them all.

43. No Milk Today

Herman’s Hermits

1967

In November of 1963, Jimmy Breslin wanted to write a column in the wake of the Kennedy assassination. But instead of jumping on a plane for Dallas like every other journalist, he did just about the opposite. Without fanfare, he flew to DC and sought out the Arlington National Cemetery groundskeeper – an elderly black gentleman – assigned to dig the president’s grave. Breslin was able to unmask a deeper and more universal truth about the impact of JFK not in something enormous, but in something small. That’s the beauty of this masterstroke of baroque pop from the remarkable Graham Gouldman, a song I remember embracing during the frigid winter of '67 even as my fellow 6th graders were insisting that Herman’s Hermits were a bunch of British "fags." But I heard this stunning song once and knew better. In it, the haunting tale of a couple’s breakup is made universal, if not universally relatable, not by something sweeping, but something achingly and almost comically mundane. In it, Gouldman distills the man’s pain and despair down to three simple words on a note left in a bottle by the door: No milk today. Amazing lyrical device from a giant of his craft.

44. Just Once in My Life

Righteous Brothers

1965

By far, my favorite Righteous Brothers tune ever; written by Gerry Goffin & Carole King, produced by Phil Spector, arranged by Jack Nitzsche, and played by some of the most talented sidemen to ever grace a set of vinyl grooves. What’s more, it was sung by two guys who, I have little doubt, were the reason a writer one day sat down at his Smith-Corona and pecked out the words “blue eyed soul” on the keyboard. Even without its pedigree, just listen to this one and discover for yourself. Just Once in My Life is the ’27 Yankees of pop songs.

45. Devil with a Blue Dress On/Good Golly Miss Molly

Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels

1966

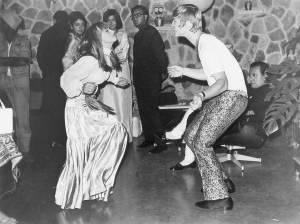

My nephew Christian was not quite three when he first heard this smoking medley. And what did the kid do that day it came on? He cocked his head in the direction of the music, then, suddenly and without warning, jumped up from the dinner table and began dancing uncontrollably. Moments later, right around the second verse, his dancing became more frenetic, and shortly thereafter more frenetic still. Eventually the kid was out of mind, swept away in the blistering organ and driving backbeat. That’s when, without any provocation, he started ripping off his clothes, and kept doing that until every last stitch lie on the ground around him, save his shoes. That, my friends, is the power of this Mitch Ryder classic, one of the truly great house rockers our generation has, or ever will ever know.

46. C’mon and Swim

Bobby Freeman

1964

The second of the two ‘60s-era dance craze songs on this list. And is it any wonder this raucous, driving and long-lost beauty so seamlessly combines the brassiness of old school R&B with the blistering guitar of modern day rock? After all, it was written and produced by a 20 year old, still wet-behind-the-ears, part-time DJ named Sylvester Stewart, who just a few years later would change his name to Sly Stone, form a multiracial band of family and friends, and begin making records that for a brief time tore down walls between musical genres, turned a blind eye toward cultural differences, and in a very real way united people of all races and colors through a brand of music that stuck out its chin defiantly and flat-out dared you to try to categorize it.

47. You Ain’t Going Nowhere

Byrds

1967

The very first time I beheld the splendor and majesty of the Rockies it was one of those textbook Colorado days, with a fresh blanket of snow on the foothills, the aspen groves quaking in full glory, and a robin’s egg blue sky above that seemed to go on forever. I was Rocky Mountain high in ways you can’t even begin to imagine. All of a sudden as I was tooling along I-70, this fabulous Dylan cover by the Gram Parsons edition of the Byrds came on the radio – it being transmitted by some low power AM station a ridge or two away, one probably being run out of some aging hippie’s woodshed. Now, I certainly have had more perfect pieces of music playing as I experienced something unforgettable, mind blowing and/or life changing for the first time. But as I sit here and write this, calling to mind that day, those mountains, and this song, for the life of me I can’t name a single one.

48. In the Midnight Hour

Wilson Pickett

1965

I’ll make this one simple; in all deference to the likes of Otis Redding, Aretha Franklin, Levi Stubbs and just every other worthy contender out there, for my money the greatest single vocal performance in the history of soul.

49. In My Room

Beach Boys

1963

For years I saw this ‘60s pop hit as just another pretty ballad from the fertile mind of music’s most famous square peg. But then, contrary to what most expected, instead of Brian Wilson being the first Wilson brother to go, something entirely unexpected happened. It was his more at-home-in-their-skin brothers who died; first Dennis, the lady-killing surfer and part-time drummer, then Carl, the one with the angelic voice. What’s more, his cousin and occasional writing partner, Mike Love up and left him too. As all this was playing out, I began viewing this tune in a significantly different light and started seeing it for what it was; one of the most eerily prescient of all Brian Wilson’s songs. Now, whenever I hear In My Room, I consider Brian’s lifetime of jagged emotions, his chronic loneliness, and his deep and abiding love for his brothers, both now gone, and I view lines like “Now it’s dark and I’m alone, but I won’t be afraid” and “Do my crying and my sighing, laugh at yesterday” so differently. Because to hear In My Room now is to imagine its singer no longer a shy kid living under mom and dad’s roof, but an aging, troubled man tired and alone, who now shares the darkness of night, not with his brothers, but with his demons.

50. Strange Feeling

Billy Stewart

1963

Now is not the time to rail about the extent to which the music industry facilitated its own demise. But suffice to say, if there was a bonehead decision to be made, the corporate wonks who foolishly tried to own music somehow managed to make it. Take, for example, their obsession with sameness and similar-sounding artists. That’s why today all country sounds the same, all hip hop seems like a variation of one song, and every contestant on American Idol, America’s Got Talent or The Voice sounds like someone who’s already been there. That’s also why radio stations now program vertically, with stacks upon stacks of similar-sounding songs piled atop one another. Which leads me to Billy Stewart, a man who in the ‘60s carved out his own path and who danced to the beat of his very own singular drummer. Listen to Stewart’s daring take on Gershwin’s slow and bluesy, Summertime. Listen to how he deconstructs and completely re-imagines an otherwise lilting ballad like Doris Day’s Secret Love. It’s amazing, and like nothing on the radio, then or now. But for my money, where Billy Stewart – a fat kid who grew up the butt of jokes, who befriended, of all people, Marvin Gaye, who was discovered by Bo Diddley, and whose life ended before it even got a chance to start when his T-Bird spun out of control and into a river – was at his best when he was harnessing his own, unique sense of melody and his uncanny knack for light-as-a-feather hooks. Because it was then that he could craft his very own brand of love song – a brand that, to this day, sounds like nothing else I've ever heard.

51. Handbags and Gladrags

Rod Stewart

1969

This one had been a sizable hit in England for singer/songwriter and former Manfred Mann front man, Mike d’Abo. But when Stewart, then of the Faces, was working on his first solo album, the evening before he was to go into the studio to lay down his version of d’Abo’s tune about a spoiled little schoolgirl and her gnawing sense of entitlement, a song that somehow managed to be both melancholy and acerbic, he knocked on the composer's door. Stewart told his fellow rocker the melancholy aspect of his tune struck him, and because of that he could hear in his mind’s ear a gentle oboe. He wondered if d’Abo wouldn’t mind writing something they could use the next day. So d’Abo worked deep into the night, and when Stewart came by in the morning what d'Abo handed him were the sheets for an oboe part that, like Jeff Lebowski’s rug, tied the whole thing together. The result was a great song made even greater; a song I could play 100 times and never tire of hearing; and one that, I have no doubt, inspired Stewart to sit down and write Maggie Mae.

52. Some Velvet Morning

Nancy Sinatra and Lee Hazlewood

1967

While he may have talked (and occasionally sung) like an uneducated drifter or red dirt farmer, make no mistake; in the 1960s few had a bigger impact on Top 40 radio, if not pop culture, than Lee Hazlewood. Hell, Phil Spector himself was little more than a glorified gopher until one day he left New York, hooked up with Hazlewood, and began absorbing everything he saw his mentor do in the studio. In fact, you know the game Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon? Well, for all the songs he wrote and/or produced, all the great sidemen he brought to light, and all sessions his fingerprints were all over, when it came to American music in the latter half of the 20th Century, you could probably cut that number in half and connect the dots between Hazlewood and any just about any record made on this soil between 1950 and 1999 in three moves or less. And yet of all the things this cosmic cowboy did, including composing hits for Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, managing to make Sinatra’s daughter Nancy seem cool by serving up for her These Boots are Made for Walkin’, teaching Duane Eddy his trademark twang, inking Gram Parsons to his first deal and then introducing him to the Byrds, recording a series of duets with Ann-Margaret, and creating a concept album about a quirky fictional Oklahoma panhandle town that felt like a sister city to Twin Peaks, this amazing, mold-breaking, one-of-a-kind single is still, to this day, my favorite Lee Hazlewood moment of them all.

53. You Know What I Mean

Turtles

1967

Allan Gordon and Garry Bonner were two young guys from Boston who one day decided to write a song for the band they were in. They did so, pressed it as a single, and the thing managed to skirt the Top 40 in a handful of east coast markets. Buoyed by their experience, the two set off for L.A., kept writing, and in time sold two tunes to Gary Lewis and the Playboys. Then one day they sat down and wrote an intentionally catchy pop tune for a bunch of L.A. kids calling themselves the Turtles. Within weeks, Happy Together became a huge hit that would grow into one of the most popular songs and largest selling singles in history. Gordon and Bonner kept writing throughout the ‘60s, and would go on to compose other hits, like Celebrate for Three Dog Night, Me About You, which the Lovin’ Spoonful released on 45 (and which made #131 on this list), and She’s My Girl and She’d Rather Be With Me for the Turtles. But no Allan Gordon and Garry Bonner song would ever touch me quite like this offbeat beauty, a song that never came close to being a hit. In fact, this slightly abbreviated, baroque-sounding 45, a symphonic cacophony of sound and garbled human emotion, did nothing at a time the Turtles, frankly, were bankable hit-makers. But that doesn’t change the fact that I can still listen to the entire two minutes and three seconds of You Know What I Mean -- a song without a chorus, mind you -- and find myself moved in a way that, despite my intimate relationship with the English language, I still somehow have trouble putting into words.

54. Last Chance to Turn Around

Gene Pitney

1966

If we were sitting around my college dorm room 40 years ago and you had told me one day I was going to assemble a list of my 300 favorite singles of the 1960s and that on my list I was going to put, not one, not two, but three Gene Pitney tunes, I would have told you to slide the towel back under the door, pass me that thing, and shut the hell up. But what can I say? Turns out I’m a sucker for the guy. Maybe it’s Pitney’s uncanny knack for recognizing a great pop song. Maybe it’s something in his records’ stunning production. Or just maybe its because no singer in my lifetime ever instilled a pop tune with a deeper sense of drama, ever sold what he was selling any more convincingly, or ever drew me into a world outside my own to any greater degree. Because even today, to listen to Last Chance to Turn Around is to hear its brushed snare drum and almost see the guy's wheels humming along the BQE. It is to feel his pain and to know the knot in his stomach as he sees the love of his life with another man. And it is watch his eyes fix ever-so-slightly on the rear view mirror as he motors past the last Brooklyn exit, and resolves in that brief moment that he will no longer be defined by what lies behind him, but, now and forever more, by what lies ahead.

55. It’s All Over Now

Rolling Stones

1964

Bobby Womack apparently hated that the Stones stole a song he wrote for himself right out from under his nose, countrified it to a degree, and (fueled by Keith Richard’s powerful, rumbling, hollow-bodied guitar) turned it into their first Top 40 U.S. hit – until, that is, month after month all those royalty checks started showing up in Womack’s mailbox. And look; I know the history of the pop charts is littered with better examples of rock guitar or rock guitar that is faster, louder, longer and more nimble than what Richard does here. I’m just not sure any guitar on any song in my lifetime has moved me to any greater degree – especially given the fact that Richard’s guitar work on this nugget is little more than a few simple chords being strummed to hell and back again.

56. You Got to Me

Neil Diamond

1967

Neil Diamond’s second album is all the proof I would need to support my long-held belief that no artist this side of Rod Stewart ever squandered more talent or ever started out his professional life so strongly only to have things come off the rails so utterly. Consider, Diamond's Just for You on Bang Records (produced by Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich). The album includes the following songs, all originals and all written solely by him: Solitary Man, I’m a Believer, Shilo, Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon, The Boat that I Row, Cherry, Cherry, Thank the Lord for the Nighttime, and this almost criminally overlooked little rocker, which is as good as any of them. But that stunning lineup of hits and near-hits is only the second most amazing fact about Diamond’s follow up to his 1966 debut, the second and final LP he would record for Bang. The most amazing? To date, Just for You has still not been released on CD.

57. Little Latin Lupe Lu

Righteous Brothers

1963

I am hardly an early adopter of anything, but years ago in BWI I bought Nick Hornsby’s High Fidelity when it was maybe a week old and still hot off the presses, and read the thing cover-to-cover on a flight to LAX, not knowing what the hell to expect. And like so many other music nuts with a trail of broken hearts in his rear view mirror, I was captivated. At one point, probably over Toledo or maybe Dayton, I began laughing so hard my body started shaking and I went into near full-blown convulsions as I tried (pitifully, as turns out) to keep things together. In time, the flight attendant even felt compelled to come up behind me, touch me on the forearm, and looking down at my tear-streamed face, ask if I was OK. Why I was laughing so uncontrollably was the scene Hornby creates during which one of the two music geeks he has working in his hero’s record store, Barry, brings in a mix tape he’d made the night before. When the store’s second geek, Dick, reading the songs on Barry's cassette box, asks which version of Little Latin Lupe Lu he chose to include, the Righteous Brothers or Mitch Ryder, Barry looks at him as though he has a cornstalk growing out of one ear and says, “Are you kidding me? The Righteous Brothers.” Dick tells Barry he’s wrong and that he should have picked Mitch Ryder. Soon things escalate, and within moments a simple discussion over the best version of a fringy 30 year old pop song has morphed into a full-blown, geek vs. geek smackdown, complete with rolling on the floor, nerd grunting and requisite playground headlock. (Sigh.) Welcome to my world.

58. Soulful Strut

Young-Holt Unlimited

1968

Late in 1968, Barbara Acklin, a talented but relatively unknown singer from Chicago went into the studio to record Am I The Same Girl, a tune written for her by her husband, Eugene Record, lead singer of the Chi-Lites. The rhythm section that day was Red Young, a bassist, and drummer Eldee Holt, jazz players who once comprised two-thirds of Ramsey Lewis’ trio. But when legendary producer Carl Davis was at the mixing board a day or so after the session, on a whim he chose to play only the track with the infectious groove established by Young and Holt, plus the one with the horn players he’d hired, omitting Ackin’s vocal track altogether. A shot went through Davis as he listened to Young, Holt and the staccato-like brassy fills, and came to the realization that he might be on to something. So on the sly he decided to hire a local jazz pianist named Floyd Morris and asked him to play whatever he felt as he listened to the playback. Davis then recorded the pianist and dropped Acklin’s vocals in favor of his breezy and understated keyboards. The resulting 45, renamed Soulful Strut, turned out to be one of the signature recordings of the decade and an unexpected hit whose simple melody was so infectious and so unforgettable that to this day it remains embedded in the minds and hearts of countless Boomers for whom ‘68 seems like both a lifetime ago and, at least on those rare occasions when they hear this little beauty, only yesterday.

59. Apples, Peaches, Pumpkin Pie

Jay & the Techniques

1967

When I was maybe 90 songs into the list you’re reading now, out of the blue one day I got a call from my friend Marcia who, as much as I love her, is not a person I see regularly or with whom I talk a whole lot. Maybe two or three times a year. Yet when I picked up the phone and identified myself, she shot out simply, quickly and, at least to me, unexpectedly, “M. Marsh. Apple, Peaches, Pumpkin Pie. Is it on there?” I answered, “Wha?” a little taken aback and without, apparently, the requisite bandwidth to fully process what she was saying. She repeated, “Apple, Peaches, Pumpkin Pie. Is it on your list? Because I gotta tell ya…If it’s not, it should be.” Not to worry Marcia. The greatest song from the greatest band to ever hail from Allentown, PA (and a song sung by Jay Proctor, arguably, the single most underrated voice in ‘60s soul music), is not only on this list, but hanging out with some lofty company and occupying some pretty rarified air.

60. Everybody’s Talkin’

Nilsson

1969

A song that as a 14 year old kid I adopted as my personal theme, probably before I even knew people could have personal themes; one that, I guess much like my life, at various times seemed awash in both hope and sadness, and one in which the love of freedom and a passion for the open road got trumped only by the eternal search for meaning and the longing desire to someday find a place to fit. And this amazing Fred Neill tune from Midnight Cowboy is a song that, like so many my age, I carried around in my heart for years. Oh, none of us may have been fully aware it was there, of course, but trust me; all you have to do is look at the stories we told, read, watched and loved – everything from On the Road, Travels with Charley, Run for Your Life and Route 66 to Easy Rider, Scarecrow, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Five Easy Pieces, The Electric Horseman and Thelma and Louise – to understand we’ve always been a generation in search of a mythical place where, indeed, the sun keeps shining through the pouring rain.